At the Battle of San Jacinto in April of 1836, the badly outnumbered Texas forces under the command of General Sam Houston avenged the historic defeat at the Alamo in San Antonio the month before by soundly crushing General Santa Anna’s vastly superior Mexican Army. After that battle, Santa Anna was forced to sign the Treaty of Velasco which granted Texas its full independence. Texas immediately declared itself a republic, with the victorious General Houston being named as its first president. However, to protect the new republic against any future invasions by Mexico, the building of a chain of forts was begun across Texas by the Republic’s militia, later assisted by units of the United States Army. In 1849, four years after Texas had been admitted as the 26th state of the Union, one of these outposts was established in central Texas on the Trinity River by the U. S. Second Dragoons and named Fort Worth in memory of the late commander of the Department of Texas, Major General Williams J. Worth, and by 1856, the town of Fort Worth had already become the seat of surrounding Tarrant County.

Immediately prior to the War Between the States the area had grown to a population of just over 6,000 inhabitants, including 850 African slaves. The county was largely in favor of secession, and in February of 1861, its citizens, like those in the other counties of Texas, and over the objections of then Governor Sam Houston, voted overwhelmingly to secede from the Union. Governor Houston, however, refused to recognize the secession vote, but the State Legislature overrode his objections and evicted Houston from office. Even though Houston was against Texas joining the Confederacy, he did not want to see his state become a battleground, and refused President Lincoln’s offer to send 50,000 troops to try and force Texas to remain in the Union. Incidentally, during the War a number of men from Fort Worth’s founding unit, the Second U. S. Dragoons, served in the Confederate Army, including two well-known general officers, Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, the defender of Savannah, Georgia, and Major General David E. Twiggs, the Second Dragoon’s first colonel.

While there were no actual battles fought around Fort Worth during the War, the effects of the conflict, as well as those of the following early Reconstruction period, ultimately had a disastrous effect on the area, with the population plummeting to as low as 175 by 1870. However, the opening of the famous Chisholm Trail a few years after the War, over which vast herds of cattle were driven from south Texas to the railhead in Abilene, Kansas, and which led directly through Fort Worth, brought a huge revival to the town and gave it the nickname of “Cowtown.” By 1873, Fort Worth’s population had risen to 500, and the town voted to become incorporated as a city. When the Texas and Pacific Rail Road began operations in Fort Worth in 1876, and the city developed its own cattle railhead, things began to really boom, with the population rising back to well over 6,000 in the next four years. By 1900 Forth Worth boasted a population of almost 26,700, and following the great Texas oil boom in the early 20th Century, by 1936 the city had become a major metropolis with about 170,000 inhabitants.

One thing which was unique about Fort Worth in the 1930s was the fact that, unlike most segregated cities in the South, as well as many so-called non-segregated municipalities in the North, Fort Worth’s large African-American population was distributed fairly equally among the various sections of the city, rather than being relegated to a single area. There was also a large and thriving African-American business district which contained a number of Black-owned hotels, stores, restaurants, night clubs, a movie theater, a bank, and a weekly newspaper, “The Fort Worth Mind,” as well as a major hospital with its own pharmacy and nursing school. There were also numerous Black schools, including the I. M. Terrell High School, and many Black churches scattered throughout the city.

1936 was also the year of the Texas Centennial which began in June in Fort Worth’s larger neighbor to the east, Dallas. Never one to be outdone by its rival city, however, a group of Fort Worth’s civic leaders led by Amon Carter, the owner of the city’s major newspaper, “The Star-Telegram,” decided to celebrate Texas’ 100th anniversary by staging its own exposition, the Texas Frontier Centennial. They engaged the celebrated Broadway showman, Billy Rose, to operate the affair, and built the fair around a huge, 4,000-seat outdoor amphitheater that contained the world’s largest rotating stage, the Casa Mañana . . . the House of Tomorrow. A well-known author and newspaper columnist of that day, Damon Runyon, said of the massive structure; “If you took the Polo Grounds and converted it into a café and then added the best Ziegfeld effects, you might get something approximating the Casa Mañana.” At the other end of the fairgrounds stood a huge indoor theater, and between these two buildings was recreated a frontier village containing such entertainment features as the Pioneer Palace, the Silver Dollar Saloon, and famous fan dancer Sally Rand’s naughty “Nude Ranch.” In the Casa Mañana, Billy Rose staged both wild west shows and musical revues like the “Streets of Paris” in which the ballad “The Night is Young and You’re So Beautiful” was introduced and became the unofficial theme song of the Centennial. Major entertainers, such as Paul Whiteman and his orchestra, were also featured at the Casa Mañana. To the indoor theater, Billy Rose brought his Broadway extravaganza, the gigantic circus musical “Jumbo.”

At the height of the exposition, however, a dark cloud began to take shape over the Casa Mañana in the form of a threatened strike by the African-American waiters led by their head waiter, Calvin Littlejohn, who would later become one of the city’s most famous photographers and the preeminent recorder of the Black community in Fort Worth. The dispute was over inadequate wages and certain working conditions, and the matter landed directly on the doorstep of Billy Rose’s auditor, my father. When Rose was retained to operate the Centennial, he turned to the National Hotel Management Company in New York City for its top auditor. At the time, my father was the technical supervisor for National Hotel Management, and had just returned to the United States from Bermuda where he had spent six months establishing an accounting and management system for the Princess Hotel in Hamilton. He was immediately assigned as Mr. Rose’s auditor, and along with my mother and myself, we repacked our bags and headed for a most interesting six-month stay in “Cowtown.”

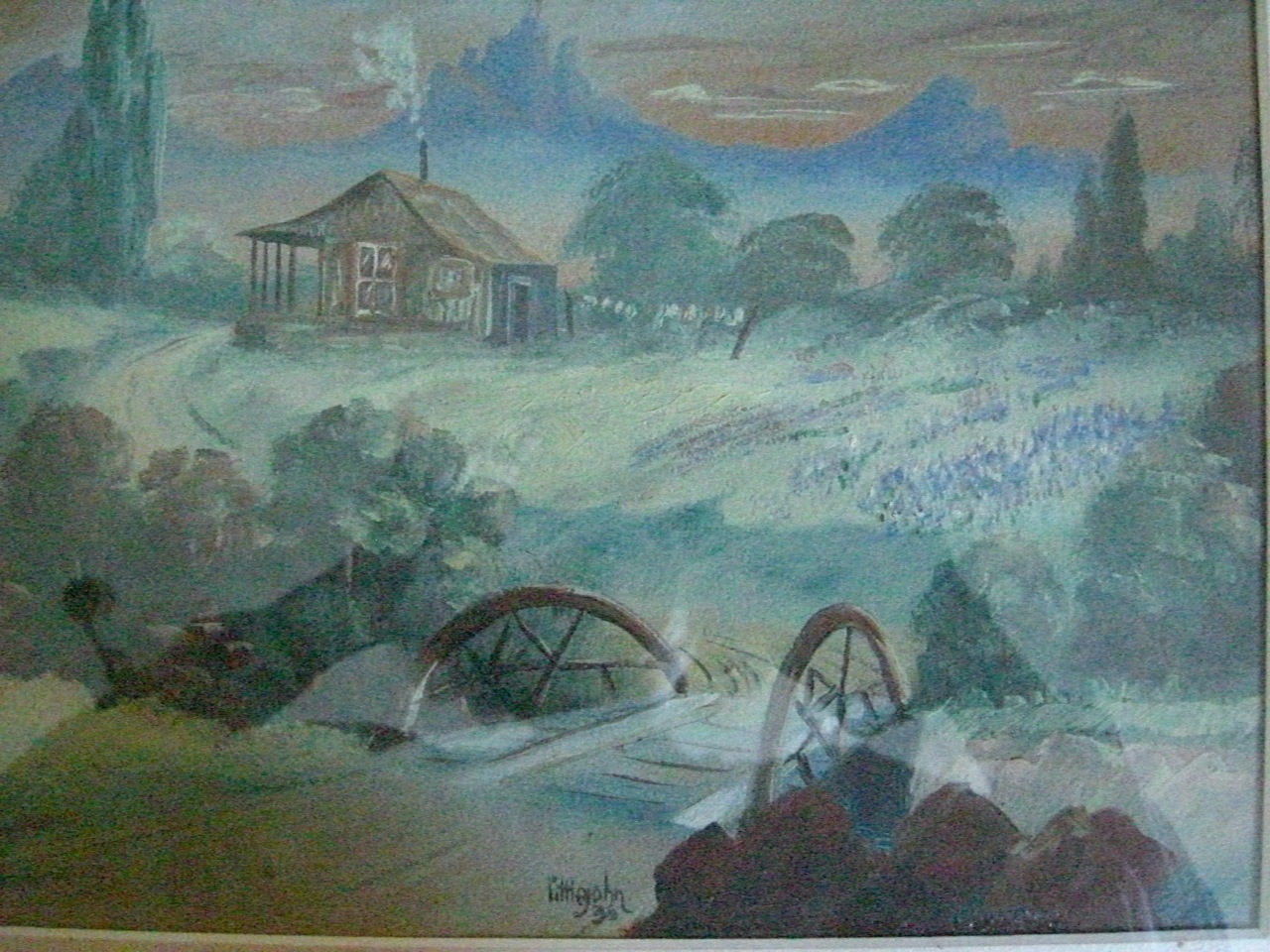

After a few meetings with Mr. Littlejohn, my father agreed that the demands of the waiters were well justified, and at his urging Billy Rose agreed to the salary increases and changes in working conditions for the waiters, and the strike was averted. While the affair received little or no publicity in the local press, it was cause for great celebration in the Black community, as well as headlines in the “Fort Worth Mind” where it was hailed as a significant victory for Negro rights. Both Billy Rose and my father did receive a few veiled threats from some anonymous Fort Worth citizens, but nothing ever came of them and the matter passed without further incident. After the settlement had been reached, Calvin Littlejohn presented my father with a lovely oil painting he had done of his boyhood home at the foot of the Ozark Mountains in Arkansas. I should add that in addition to his later skill as a photographer, Calvin Littlejohn, who had studied art at Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas, was also a fine amateur painter. After the Centennial, he also taught industrial arts in the Fort Worth school system, as well as becoming the first official photographer for the I. M. Terrell High School. From the time I was seven years of age in Fort Worth, the Littlejohn painting has always been with me, and now hangs in my home in Tokyo.