This piece was originally published June 3, 2014 at the Abbeville Blog.

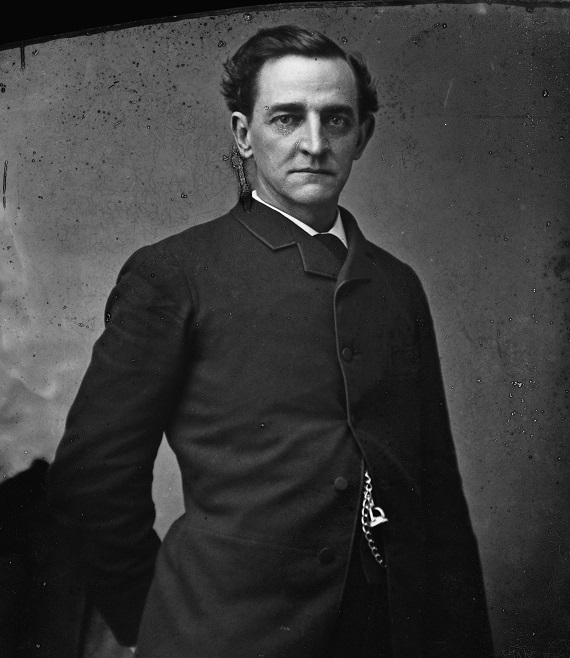

Senator John Warwick Daniel (1842-1910) of Lynchburg, Virginia was a gentleman’s gentleman. Daniel served in the U.S. Senate from 1887 until his death in 1910 and was known as “The Lame Lion of Lynchburg” after being severely wounded in the War for Southern Independence. He was shot through the hip at First Manassas and struggled off the battlefield using two rifles for crutches. He removed a bullet from his hand with a pocketknife during the defense of Richmond in 1862, and he was permanently disabled after trying to rally his men at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. He nearly bled to death. His political career was marked by the same staunch defense of the South and State’s rights. One contemporary remarked:

I fancy that John Daniel would have named Thomas Jefferson as the greatest American statesman; certainly his own political instincts and ideals were largely those which Jefferson had caused to prevail. Like Jefferson, he trusted the people of his country, because by close intimacy and wide experience he had found them worthy of trust and believed them also worthy of freedom and political power. His abiding faith in the honesty of his fellow citizens, his rooted belief in their common sense, his trust in the appeal to the educated reason of the voters, his assurance that human society is capable of indefinite advancement in virtue and uprightness, his firm conviction that majorities rule not by might alone but of right as well, made of Thomas Jefferson the typical American and the like qualities made of John Daniel the typical Jeffersonian Democrat.

Daniel lived in a time when Southern men and women were required to understand the lives and character of Confederate heroes and to do so publicly. Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina had a humorous story about this in 1973 (Youtube below); fully 100 years after the War, Ervin recounts, Southerners were expected to know their history. Such is not the case today. Any whiff of an attachment to Confederate leaders or the traditional South means certain political death, even in Dixie it seems.

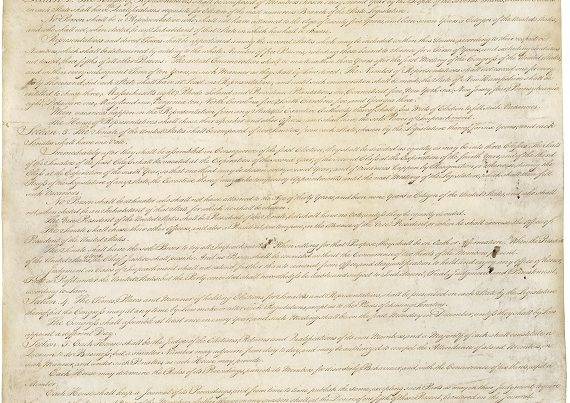

Daniel was asked to speak about Jefferson Davis’s life and character before the Virginia Legislature in 1890, just one year after the former President’s death. His purpose was to honor the man and his legacy and to vindicate the South and its struggle for independence. Daniel said, “Jefferson Davis never advocated an idea that did not have its foundation in the Declaration of Independence; that was not deducible from the Constitution of the United States as the fathers who made it interpreted its meaning; that had not been rung in his ears and stamped upon his heart from the hour when his father baptized him in the name of Jefferson and he first saw the light in a Commonwealth (Kentucky) that was yet vocal with the States’-Rights Resolutions of 1798.” Davis, Daniel insisted, should have been etched in stone among the great pantheon of world heroes. His cause was that of America.

Daniel asked, “Did not the South love American institutions? What school-boy cannot tell? Who wrote the great Declaration? Who threw down the gage, “Liberty or Death?” Who was chief framer of the Constitution? Who became its great expounder? Who wrote the Bill of Rights which is copied far and wide by free commonwealths? Who presided over the convention that made the Constitution and became in field and council its all in all defender? Jefferson, Henry, Madison, Marshall, Mason, Washington, speak from your graves and give the answer.”

And Daniel emphasized that American history had been defined by the South, from the Old Northwest territory to Texas, Southerners had led the charge to settle North America, to bring America to the West, and by America he meant the principles that defined the South: liberty, independence, and free government. Their cause was that of the patriot who rode to battle against the British in 1776, both North and South.

Daniel believed, somewhat optimistically, that in the future the American people would remember Jefferson Davis as a hero rather than a traitor. All signs pointed in that direction in 1890. Lee and Jackson were considered American heroes. Davis resisted the charge for secession in the months prior to Mississippi withdrawing from the Union in 1861, and his farewell address to the Senate was considered to be one of the most eloquent and beautiful in American history. He loved the Union and he loved America, no less so than Abraham Lincoln, perhaps even more deeply. Daniel, of course, could not see the tornado of political correctness that would eventually dislodge free thought and free speech from the foundation of American discourse.

In the same year, 1890, Daniel edited and published a substantial book on Davis titled Life and Reminiscences of Jefferson Davis. He dedicated it to, “THE PEOPLE OF THE SOUTH TO YOU IS DEDICATED THIS MEMORIAL VOLUME OF YOUR HONORED AND MUCH LOVED CHIEFTAIN JEFFERSON DAVIS, THE STATESMAN, SOLDIER, AND CHRISTIAN, IN WHOM WAS EMBODIED AS IN NO OTHER MAN THE POLITICAL VIEWS AND SENTIMENTS, WHICH YOU SO ABLY MAINTAINED IN THAT MEMORABLE CONFLICT OF 1861-65.” Over half the tome contains contemporary accounts of Davis as a man, a statesman, and an American.

Daniel introduced the book with a sentence that still rings true one-hundred and twenty-four years later, “Jefferson Davis has been more misrepresented, and is to-day more misunderstood by many than any character that figured in the Civil War of 1861 to 1864 [sic].” Daniel thought this was the result of Davis’s character, most importantly his refusal to ask for a pardon after the War. Yet, he considered Davis to be “one of the purest and bravest of the public men which our country has produced;—that he was an honest, able and clear thinker, and a true seeker for the good of humanity. He was the incarnation of the Southern cause.” It would only be natural, Daniel opined, for Americans to see his importance. Had not lesser men been vindicated by time?

Daniel argued Davis exemplified everything America stood for, both past and present. “The character of Jefferson Davis,” Daniel wrote, “will grow, in the general estimate. Scholars will ponder it, and will bring to the light the facts which have been neglected or ignored; and statesmen who have been under the spur of interest to paint him darkly, will feel that impulse to do justice which springs up from a sense of injustice done. A ripe scholar, a vigorous writer, a splendid orator, a brave soldier, a true gentleman, an accomplished statesman, a sturdy champion, a proud, pure patriot, a lover of liberty, a hero: this is the Jefferson Davis that history will cherish.”

Davis and the South lost the War, but would not Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Rutledge, Marion, Macon, Taylor, Mason, Henry and other Southerners suffer the fate of their Confederate descendants had they lost the War for American Independence? Would Americans reduce their glory and place Gage, Cornwallis, and George III above their honor? The heroes who waged a war for the “Principles of ’76” shared a common cause with the patriots of 1861, and on Jefferson Davis’s birthday, all Southerners, nay all Americans, should remember that fact. Daniel was simply speaking the truth. After all, he had bled for it, and his body had been shattered defending it. Davis nearly rotted to death in prison after the War facing charges for a crime he did not commit, treason. The truth set him free and vindicated his cause. The truth led the Lame Lion of Lynchburg to honor his former President. The truth led millions of Southerners to defend Davis, even into the late 20th century. That doesn’t mean much today, but it should.