The Tricentennial celebration of New Orleans has stirred much interest into different facets of the city’s history. The search for the quintessential old New Orleans novel yields few results.

The rich culture of New Orleans makes it one of America’s great cities. The Crescent City has served as muse for a litany of writers, accomplished and rising, yet it remains a near impossible place for fiction writers to capture and receive both popular acclaim and approval from the natives. Only a few pieces written about New Orleans are truly beloved locally. And the city has plenty contrarians who argue against celebrated works such as A Streetcar Named Desire and A Confederacy of Dunces. This isn’t a new development: New Orleanians have rarely embraced creative representations of the city, even when they are popular.

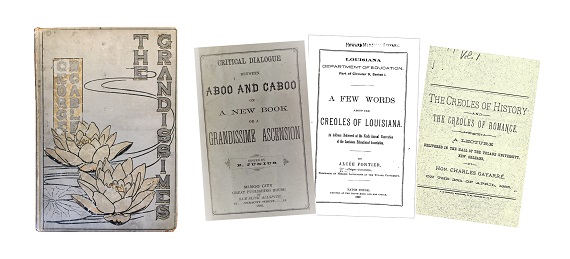

One book, published almost 140 years ago, serves as an example of the nationally-acclaimed-yet-locally-hated New Orleans novel. George Washington Cable first published The Grandissimes serially before Scribner’s released it as a novel in 1880. Subtitled “A Story of Creole Life” and set in 1803-04, the novel acquainted America with what Cable presented as traditional French Louisiana.

The Grandissimes takes place in New Orleans at the time of the Louisiana Purchase, when “Nouvelle Orleans had become New Orleans, and Louisiane was Louisiana.” In the novel the French Creole aristocratic society faced changes with the American takeover of their world. The name Grandissime (grahn-dees-EEM) translates to “grandest of all” and Cable claims the Grandissime clan to be the greatest Louisiana family.

The portrayal of Louisiana in 1803 and ‘04 caused a stir locally. The author did not live then or even have roots in the region during that time. Cable was born in New Orleans in 1844 and raised in the city, however, he was far from old line Louisiana. His father was from Virginia and his mother was from New England. The Cables transplanted from Indiana to New Orleans in 1837.

Cable fought in the Mississippi Cavalry during the Civil War from 1862 until the war’s end in 1865. After the war he worked in shipping and then as a journalist for The Daily Picayune. As a novelist, Cable mainly wrote about old New Orleans. For a Confederate combat veteran, his writing was progressive.

Cable’s writing style and the characters he created were unconventional. This is an example of the dialect Cable used for prominent Creole character, Madame Aurora De Grapion-Nancanou: “Hanny ’ow, I know she continue in love wid ’im all doze ten year ’w’at ’e been gone. She baig Mademoiselle Grandissime to wrad dad ledder to my papa to ass to kip her two years mo’.”

And as another example, this quotation belongs to Raoul Innerarity, a Grandissime: “Well, — ce’t’nly ’e did! Di’n’ ‘e gave dat money to Aurora De Grapion? — one ’undred five t’ousan’ dolla’? Jis’ as if to say, ’Yeh’s de money my h-uncle stole from you’ ’usban’.’ Hah! w’en I will swear on a stack of Bible’ as ’igh as yo’ head, dat Agricole win dat ’abitation fair! — If I see it? No, sir; I don’t ’ave to see it! I’ll swear to it! Hah!”

When published, Cable’s work was acclaimed by critics while criticized by locals. In 1880, The Grandissimes was hailed a “superb novel” and “among the strongest works of fiction that have appeared in American literature” in newspapers across the country. The New York Times called it “a wonderful romance.” The Baltimore Gazette declared Cable “the genius of a novelist of the first rank.” And The Boston Journal said Cable was “a novelist of positive originality, and of the very first quality.” The north loved George Washington Cable, but the South—and New Orleans in particular—held quite the opposite opinion.

The author became the focus of a literary onslaught. Three of Louisiana’s most established writers at the time, all of Creole lineage, publicly challenged Cable. Alcée Fortier, Charles Gayarré, and Adrien Rouquette wrote pamphlets attacking the author and, as the descendants of the ancient French and Spanish population, defended the heritage of an estimated 250,000 Louisianians.

Rouquette, a Catholic priest and poet popular in Louisiana and France, ghost wrote Critical Dialogue Between Aboo and Caboo on a New Book or A Grandissime Ascension. The 24 page pamphlet is a conversation between two Grandissimes, using the names Aboo and Caboo, as they criticize and critique the acclaimed novel for its portrayal of Creoles, its positive reception in the North, the ridiculous dialogue, and of Cable the “untruthful Novelist.” Rouquette called Cable “a scoffer, a banterer, a ridiculer.”

The poet-priest accused Cable of having “slanderously misrepresented” the customs, habits, and manners of the French people that originally settled South Louisiana and established La Nouvelle Orleans. The novel is described as a “swindling publication,” “written with a malignant spirit.”

The insults against Cable included “polished banditti,” “ill-natured alien,” “sleek, shrewed peddler of novelties,” “slime-imbedded alligator,” “evil-eyed Caricaturist,” “unfledged dwarf who has insulted a noble population,” and “unscrupulous falsificator.”

Roquette, as well as his brethren of infuriated Creoles, refuted both The Grandissimes and Cable’s previous effort, Old Creole Days. “They were given as novels and they have been taken for HISTORY,” Roquette wrote. He also compared Cable to Chef Menteur, recalling the old story about the Choctaw Chieftan with a loose tongue who was labeled “Lying Chief” and exiled to what is now New Orleans East.

In the conversation of the pamphlet, Aboo said The Grandissimes’ “fit title should have been ‘The Fictions of Ridicule;’ which book is neither historical nor romantic, in any true sense of what we term history or romance.”

Aboo said, “so mischievously altered and confused are dates, events, places, things, names and persons; and all this to the sole intent, the wicked purpose of slur, travesty and ridicule—leeringly—sneeringly—jeeringly.”

Caboo went after Cable’s dialogue, describing it as a “hissing, whistling, howling, drunken ‘mob’ of tortured English words… the worst patois that ever grated the human ear.”

Historian, statesman, and Creole Charles Gayarré deconstructed Cable’s depiction of the ancient families of La Louisiane. He gave a lecture titled The Creoles of History and the Creoles of Romance “to protect the reputation of those ancestors who cannot come out of their graves to face and refute defamation.” He recounted the origin of the term “creole” and the history of the colony until a few years after the conclusion of The Grandissimes.

In his lecture, which was also published, Gayarré unleashed his own attacks upon Cable, referring to him as a “romancing libeler” and “modern slanderer.” As to the controversial novels, the historian dismissed them as “malicious compositions,” “monstrous absurdities,” “published with unaccountable malignity,” “audacious mutilation of what is truth,” “perversion of depravity of his intellect,” and a “violation of truth.”

George Washington Cable wrote that the “pilgrim fathers of the Mississippi Delta” made wives of Indians, African slaves, and French prostitutes. Gayarré called this a “gratuitous insult to a whole nation.” Creoles took umbrage that Cable’s depiction created the misconception that Creoles were not of pure bloodlines. This allegation was strongly rebuked.

The term Creole originally denoted those born in a new colony with French or Spanish parents. When Creole, originally criolla, was applied to French, Spanish, or Africans, it identified them as natives born in Louisiane. The definition has evolved several times, but George Washington Cable may be more responsible than any other person for creating the false notion that the word “Creole” denotes a racially mixed people.

“There is nothing so impure as what is mentioned in certain works of fiction that have been accepted as historical. … A population whose best men, according to the same authority, are bullies, knaves and fools, with the brains of a jackass, the heart of an alligator, and the tongue of a gibberish monkey. … I have carried his famous novel to intelligent negroes who could read, and not one of them could understand the spelling and pronunciation of the language attributed to their race. … Nothing else could be expected from Mr. Cable, whose aim, through his whole book, is to vilify what is reputed noble, and to enoble what is reputed vile.”

Gayarré further challenged Cable to name two Creole families that he knew closely—Cable admitted he could not.

Alcée Fortier, a linguist, educator, and writer, obsessed over Cable’s portrayals of his ancestral class. Fortier penned two pamphlets in response to Cable’s novels titled The French Language in Louisiana and the Negro-French Dialect and A Few Words About the Creoles of Louisiana.

Fortier razed the political-transition foundation the novel is set upon. La Nouvelle Orleans may have become New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase, but decades spanned before the French people acclimated to America. Fortier explained that for roughly 40 years the French people in Louisiana did not learn English. And for decades longer, the Louisiana legislature retained an interpreter well into the 1800’s to help translate motions and conversations between the French and English speaking elected officials. The political backdrop Cable used, the transition to Americanism, was another inaccurate and fabricated part of The Grandissimes.

Creoles “were, in short, men of energy, in spite of Mr. Cable’s assertion to the contrary, and they spoke, as a rule, very good French,” Fortier wrote in The French Language in Louisiana. “The Louisianians generally pronounce French well.”

Fortier provided an academic explanation of the shift in languages. For instance, he related how the French language evolved from abbreviated Latin and applied that to how the French spoken by black people in Louisiana evolved from their abbreviation of classic French. And that the true pronunciations do not resemble Cable’s dialogue.

In A Few Words About the Creoles of Louisiana, Fortier tells stories of Creole strength and accomplishments. He wrote that:

“we have been maligned and misrepresented. … Most of the Creoles are descended from the casket girls, or worse still, says a certain writer. Where are his proofs? … I wish to protest against unfounded statements. … Have you ever seen more insignificant dolls, or more superstitious idiots? They speak an extraordinary English, which language, by the way, no Creole spoke in Louisiana at that time, and they are dreadfully afraid of voudous. …They have been described so fantastically that Northern men coming to New Orleans look for them as they would for wild beasts in a menagerie. …As to the jargon attributed to the Creoles, it is a surprising invention. … The assertions of Mr. Cable, for at last he must be named, are so absurd and ridiculous that they would hardly deserve to be noticed if they were not at the same time so malignant and insulting to everything which we hold sacred, to the memory of our fathers, to our mothers and sisters, and to ourselves.”

In closing, Fortier wrote that his very imperfect and hastily sketched lecture “is sufficient to show that our State has no cause to regret that her first born, her oldest ones, are the Creoles of Louisiana.”

The local uproar against George Washington Cable is clearly evidenced by the works of these noted men. Following his literary success, Cable was viewed in his home town as a cultural scalawag. With the locals enraged by his characterizations of their proud heritage, Cable moved to Massachusetts in 1885 and never lived in the Crescent City again. In reality, Cable’s controversial depiction of New Orleanians led to him being run out of town.

After his death, Cable’s obituary in the New Orleans States noted the local criticism that followed his publications and wrote that “some of the most prominent Creole families closed their doors against Cable.” While an obituary should not have, out of good taste, expounded upon this, it was quite an understatement.

The flaw of The Grandissimes seems to be that the author wrote a period piece rampant with historical inaccuracies. Cable slyly and subtly spun history to dethrone the aristocratic noblesse. He crafted a unique people into an unflattering and largely flawed character. Cable used language in The Grandissimes which insulted the intelligence of all natives of Louisiana, from the enslaved to the grandest of them all.

New Orleanians protect their culture and do not tolerate misrepresentations of it. Maintaining the historic integrity of New Orleans is paramount to preserving the past for the future. Satirizing Creoles and using creative liberties to alter their character, even in fiction, can impact that authenticity. New Orleans has incredible history. New Orleanians demand accuracy. That applies to all efforts to falsify history.

Representations altering the truth will be subjected to harsh criticism—it’s tradition.