What to say in brief compass about the South?—a subject that is worthy of the complete works of a Homer, a Shakespeare, or a Faulkner. The South is a geographical/historical/cultural reality that has provided a crucial source of identity for millions of people for three centuries. Long before there was an entity known as “the United States of America.” there was the South. Possibly, there will still be a Southern people long after the American Empire has col¬lapsed upon its hollow shell.

One fine historian defined the South as “not quite a nation within the nation, but the next thing to it.” The late M.E. Bradford, whose genial spirit watches over us even now, defined the South as “a vital and long-lasting bond, a corporate identity assumed by those who have contributed to it.” This is, characteristically, a broad and generous definition. He proceeded to illustrate that when visualizing the South, he always thought “of Lee in the Wilderness that day when his men refused to let him assume a position in the line of fire and tugged at the bridle of Traveler until they had turned him aside.” This was clearly a society at war, not a government military machine.

The South is larger and more salient in population, territory, historical import, distinctive folkways, music, and literature than many of the separate nations of the earth. Were the South independent today, it would be the fourth or fifth largest economy in the world. Citizens of Minneapolis consider them¬selves cultured because of their Japanese-conducted symphony that plays European music, and assume that the Nashville geniuses who create music all the world loves are rubes and hayseeds. New Yorkers pride themselves on their literary culture. Yet in the second half of the 20th century, if you subtract Southern writers. American literature would be on par with Denmark or Bulgaria and somewhere below Norway and Rumania.

Southerners are the most regionally loyal citizens of the United States. But paradoxically—or perhaps not—they have traditionally been the most loyal to the country at large, ready to repel insult or injury without the need to be dragooned by any ridiculous folderol about saving Haiti or Somalia for democracy. Southerners have given freely to the Union and generally avoided the demands for entitlements that now characterize American life. But their loyalty has been severely tested, especially considering all they have ever asked in return is to be left alone.

Southerners have less reason to be loyal to the collective enterprise of the United States than does any group of citizens. The South was invaded, laid waste, and conquered when it tried to uphold the original and correct understanding of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. It took 22 million Northerners, aided by the entire plutocracy and proletariat of the world, four years of the bloodiest warfare in American history and the most unparalleled terrorism against civilians, to subdue five million Southerners—all followed by the horror of Reconstruction. During this entire period, “the Northern conservatives” never opposed the smallest obstacle to the devastations of the radicals. In fact, the Northern “conservatives” have never, in the course of American history, conserved anything.

Since the War, the South has been a colonial possession, economically and culturally, to whatever sleazy elements have been able to exercise national power. A major theme of the American media and popular culture is ridicule and contempt for everything Southern. A major theme of American historical writing is the portrayal of the South as the unique repository of evil in a society that is otherwise shining and pure.

A severely condensed but essentially accurate interpretation of American history could be stated thusly. There are two kinds of Americans. There are those who want to be left alone to pursue their destiny, restrained only by tradition and religion: and those whose identity revolves around compelling others to submit to their own manufactured vision of the good society.

These two aspects of American culture were formed in the 17th century, by the Virginians and Yankees, respectively. The Virginians moved into the interior of America and carved their farms and plantations out of the wilderness. Their goal was to re-create the best of English rural society. They merged with even more vigorous and independent people, the Scots-Irish, to form what is still the better side of the American character.

The Yankees of Massachusetts lived in villages with preacher and teacher. They viewed themselves as a superior, chosen people, a City upon a Hill. As far as they were concerned, they were the true Americans and the only Americans that counted, ignoring or slandering other Americans relentlessly — a sentiment persisting to this day.

The days of Jefferson and Jackson illustrate the freedom and honor underlying America when ruled by the South. During their eras, Virginians gave away their vast Western empire for the joint enjoyment of all Americans, (thus making possible the Midwest and West) and labored to erect a limited, responsible government. The New Englanders, during the same periods, demanded a reserve of lands for themselves in Ohio; instituted a national bank and funding system by which their money-men profited off the blood of the Revolution: passed the Alien and Sedition laws to essentially enforce their own narrow ideological code on others; opposed the Louisiana Purchase; and demanded tariffs to protect their industries at others’ expense. All of which was done in the name of “Americanism.”

This profiteering through government, which John Taylor of Caroline called the “paper aristocracy,” has always been accompanied by moral imperialism and assumptions of superiority that are even more offensive than the looting. It is from this that the South seceded. It is this combination of greed and moralism which constitutes the Yankee legacy, gives the American empire whatever legitimacy it can claim, and fuels the never-ending reconstruction of society. That is why we use Marines for social work, so that our leaders can congratulate themselves on their moral posture. That is why every town in the land is burdened with empty parking spaces bearing the symbol of the empire, so that the Connecticut Yankee George Bush can posture over his charity to the disabled. That is why, right now, wealthy Harvard University receives from the treasury a 200 percent overhead bonus on its immense federal grants, while the impoverished University of South Carolina receives only 50 percent of its much smaller bounty.

The term American is an abstraction without human content —it refers, at best, to a government, territory, standard of living, and a set of dubious and dubiously observed propositions. It refers to nothing akin to values or culture, nothing that represents the humanness of human beings. It could be reasonably argued that there is no such thing as an American people, although we have persuaded ourselves there was when shouldering the burdens of several wars. There was perhaps a time earlier in this century when an American nationality might have emerged naturally. But that time has passed with the onslaught of new immigrants.

Unlike the term American, when we say Southern, we know we imply a certain history, literature, music, and speech: particular folkways, attitudes and manners: a certain set of political responses and pieties: and a traditional view of the proper dividing line between the private and the public. Things which are unique, easily observable, and continual over many generations.

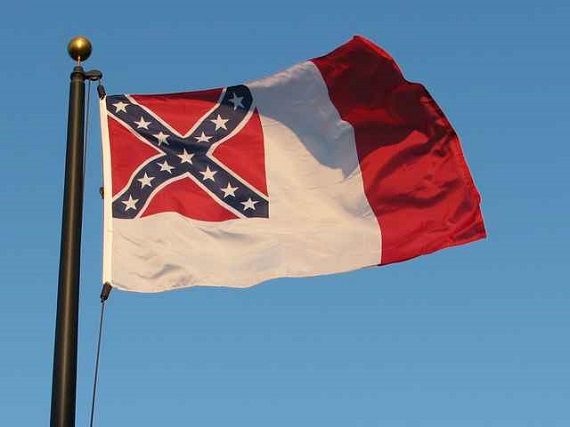

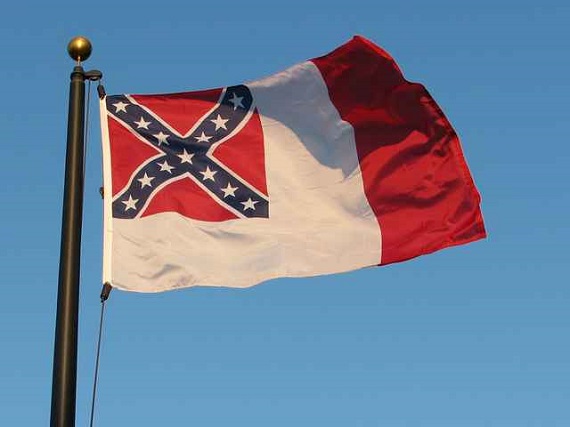

The bloody St. Andrews cross of the Confederacy is a symbol throughout the world of heroic resistance to oppression —except in the U.S., where it is in the process of suppression. Southerners are democratic in spirit, but they have never made a fetish of democracy and certainly not of what Mel Bradford called “Equality.” With T.S. Eliot, Southerners intuitively recognize that democracy is a procedure and not a goal, a content, or a substitute for an authentic social fabric. However free and equal we may be, we are nothing without a culture, and there is no culture without religion.

The South, many believe, still has a substantial authentic culture, both high and folk, and it still has a purchase on Christianity. That is, the South is a civilizational reality in a sense which the United States is not, and it will last longer than the American Empire.

For a long time we have been asking what the South can do for the United States. A proper question to now ask is what can the United States do for the South? The Union is nothing except for its constituent parts. The Union is good and just to the degree that it fosters its authentic parts. That is precisely why our forefathers made the Constitution and the Union and gave consent, voluntarily, to them —to enhance themselves, not the government.

As the Southern poet Allen Tate pointed out, the wrong turn was taken in the War Between the States when the United States ceased living by the Southern conception of a limited partnership and became instead a collection of buildings in Washington from which orders of self-justifying authority were issued. The great classical scholar and Confederate soldier Basil Gildersleeve remarked that the War was a conflict over grammar—whether the proper grammar was “the United States are” or “the United States is.” We have been using the wrong grammar.

The South’s lost political legacy was laid out by Rev. Robert Lewis Dabney, Presbyterian theologian and Stonewall Jackson’s chief of staff, several years following the War. Echoing Calhoun he said:

Government is not the creator but the creature of human society. The Government has no mission from God to make the community, on the contrary the community is determined by Providence, where it is happily determined for us by far other causes than the meddling of governments—by historical causes in the distant past, by vital ideas, propagated by great individual minds—especially by the church and its doctrines. The only communities which have had their characters manufactured for them by governments have had a villainously bad character. Noble races make their governments. Ignoble ones are made by them.

The United States was created to serve the communities which make it up, not for the communities to serve the government. That is what the South and all authentic American communities need to recapture from a ruling class bent upon constantly remaking us. If we recapture that, we will again be citizens giving our consent to the necessary evil of a limited government, and not the serfs and cannon fodder of the American Empire.