“The one great principle, which produced our secession from the United States – was constitutional liberty – liberty protected by law. For this, we have fought; for this, our people have died. To preserve and cherish this sacred principle, constituting as it did, the very soul of independence itself, was the clear dictate of all honest – all wise statesmanship.”– Robert B. Rhett

It is fashionable nowadays to regard States’ rights as yet another debunked “Neo-Confederate” myth. One Bancroft-winning historian takes the incredible liberty of inserting imaginary thoughts into prominent Fire-Eater Robert B. Rhett’s head, having him curse “St. Thomas” Jefferson, along with “inalienable rights,” “rights of revolution,” and “the principles of 1776,” claiming “the South had revolted to escape those idiocies.” Never mind the fact that Rhett proclaimed these very ideals throughout his life and personally identified as a “Jeffersonian Republican.” Elsewhere, a winner of the Alan Nevins History Prize writes off the sincerity of States’ rights with a few words. “As for the ‘dry prattle’ about the Constitution, the rights of minorities, and the like, there was never any confusion in the minds of most contemporaries that such arguments were masks for more fundamental emotional issues,” he casually asserts. “State sovereignty was an issue only because the retreat to the inviolability of states’ rights had always been a refuge for those fearful of a challenge to their property.” Indeed, it is the modis operandi of historians nowadays to discount whatever Southerners said about political, economic, and cultural differences with the North as a false front for the ulterior motive of slavery: Southerners could not possibly have meant what they said!

This essay series aims to right the wrongs which the commissars of acceptable opinion in academia and the media have inflicted upon the role of States’ rights in Southern history. An honest study of the great political treatises of the Old South proves that the doctrine of States’ rights was never a mere pretense for slavery, but reflected a deep passion for self-government rooted in Southern culture as well as an earnest understanding of the Constitution rooted in Southern history. According to the distinguished M.E. Bradford, States’ rights were a “patrimony” and “birthright,” dating from the foundation of the Colonies through the independence of the States and to the creation of the Constitution. President Jefferson Davis, at the crowning of the Confederate capital in Richmond, dubbed this heritage “the richest inheritance that ever fell to man, and which it is our sacred duty to transmit untarnished to our children.” Robert B. Rhett’s Address of South Carolina to the People of the Slaveholding States, promulgated in 1860 by the secession convention in Charleston, is the subject of this essay.

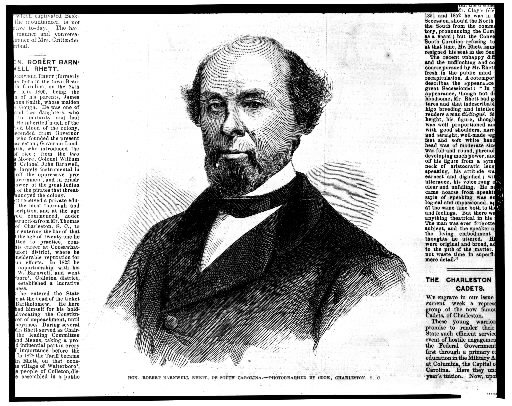

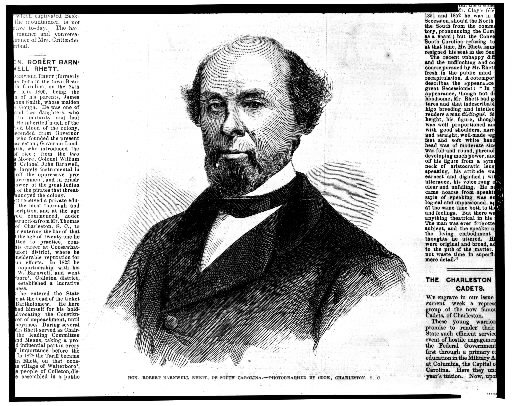

Robert Barnwell Smith (aka “Rhett”) was born on December 21, 1800, in the old Lowcountry district of Beaufort, South Carolina. With one of the most distinguished lineages in the State – descended from six governors, two landgraves, and the very first settler of South Carolina – Smith aspired to make his ancestors proud and was committed to protecting his people’s inherited way of life. Smith’s father, James, was a soldier of the American Revolution who had defended the besieged cities of Savannah and Charleston, and been taken prisoner when the latter fell. Smith attended Beaufort College, where he was impressed with the integrity of the staunch Unionist James Petigru. “It is only the strong man – strong in conscious rectitude, strong in convictions of truth, strong in the never-failing and eternal vindications of time – who can put aside the temptations of present power, and submit to official inferiority,” reflected Smith. “Superficial observers may not understand the greatness of such a man.” A shy student, Smith was nicknamed “Madame Modesty.” Due to his father’s troubled finances, Smith had to leave Beaufort College and be tutored by his father, who imparted his Jeffersonian politics to his son. “I was…raised and nurtured a Republican, in the faith and principles of my Father,” recalled Smith.

Smith was born and bred past the glory days of the republic in a time of strife between sections and parties. To Smith, the Union did not stand for peace and prosperity, as it did for his father, but oppression and corruption – a threat to the “free government” for which his father had fought. Indeed, rumblings were emerging from Beaufort, a staunch Federalist stronghold in the Jeffersonian South, over the tariff bills of 1816 and 1824, which enriched Northern industry at the expense of Southern agriculture. These tariffs (“nothing but robbery”), the Missouri Compromise (which “nullified the sovereignty of the people”), and the corruption of the Democratic-Republican Party (“little more than a mere association to obtain office and power”) convinced Smith to run for office in the State legislature. Elected in 1826, Madame Modesty came out of his shell as a “brilliant and promising young man,” according to one of his friends.

Amid this tense atmosphere of sectionalism, a volcano erupted in Smith’s district. At a citizens’ meeting in 1827, Smith authored a memorial to the Congress protesting protectionism in general (labeled the “American System” by its supporters) and a proposed tariff on woolens in particular. “From the moderation of our Northern Brethren, who for the last ten years have been beating at our doors for monopolies,” announced Smith, “we have renounced all hope.” Smith argued that “free commerce is the true interest of every nation,” but that while the South supplied the bulk of American exports, she also paid the bulk in federal taxes, most of which was redistributed to the North as so-called internal improvements. “It is immaterial whether that money is received by one man called a King or by thousands termed Manufacturers.” Smith closed with a veiled threat of resistance if the unconstitutional and exploitative tariff were not abandoned. “Do not add oppression to embarrassment, and alienate our affections from the home our fathers together raised,” warned Smith. “Do not believe us degenerate from our sires, and that we will either bear or dare less, when the time for suffering or resistance comes.” The Woolens Tariff was defeated, but the next year, in response to the Tariff of Abominations – a much more comprehensive tax increase – Smith authored a second memorial at another citizens’ meeting, doubling down on his previous statements and dealing a broadside against the American System. Smith labeled the Tariff of Abominations “a timid fraud well-becoming the tyranny it covers” and claimed that it dwarfed the oppression which their forefathers faced from Britain. Before, Smith had merely threatened resistance, but now he openly called for it. “We must either retrograde in dishonor and in shame, and receive the contempt and scorn of our brethren, superadded to our wrongs, and their system of oppression, strengthened by our toleration,” insisted Smith. “Or we must,” he finished with a Shakespearean flourish, “‘by opposing, end them.’” According to Smith, resistance to federal tyranny stemmed “not from a desire of disunion, or to destroy the Constitution, but…that we may preserve the Union, and bring back the Constitution to its original uncorrupted principles.” Smith’s memorials electrified the United States and catapulted him into prominence. They were his first act of defiance against the federal government and would not be his last.

Smith’s memorials made an ultimatum to the Congress: repeal the Tariff of Abominations or South Carolina would secede from the Union. Smith believed that if South Carolina forced the issue by seceding, other States would take her side and the Congress would have no choice but to compromise. When Vice President John C. Calhoun, seeking to prevent civil war and preserve South Carolina’s rights, proposed nullification – a renewed application of the Principles of ’98 from Jefferson and Madison’s Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions – Smith relented from secession, though he maintained skepticism of a “peaceful remedy.” Nevertheless, Smith embraced Calhoun’s strategy, leading the call for a State convention and attending States’ rights rallies all around South Carolina to galvanize support for nullification. “Standing, then, upon the very ground which Mr. Jefferson, Mr. Madison, and the whole Republican Party stood in ’98,” avowed Smith, “we think that the time has come when our principles are to be enforced – peaceably – constitutionally enforced – when Carolina, as a sovereign party to the constitutional compact, should interpose ‘for arresting the progress of evil.’” Revolution? “What, sir, has the people ever gained, but by revolution?” retorted Smith. “What, sir, has Carolina ever obtained great or free, but by revolution? Revolution! Sir, it is the dearest and holiest word to the brave and free.” Disunion? “Washington was a disunionist, Adams, Henry, Jefferson, Rutledge, were all disunionists and traitors, and for maintaining the very constitutional principles for which we now contend. They severed a mighty empire on whose dominion the sun never set…they cut this empire asunder with the stern energy of the sword,” answered Smith. “Shall we, standing upon the free soil of Carolina, rendered sacred by the bones of our Revolutionary martyrs and heroes…tremble at epithets?” A serious illness prevented Smith from attending the nullification convention in 1832, although after the ordinance passed he was allowed to add his signature in recognition of his contribution to the cause.

When no States seconded nullification and President Andrew Jackson prepared for an invasion, South Carolina’s position looked grim. In 1833, the State convention reassembled to consider the compromise that Calhoun had helped secure – a gradual reduction of the tariff in exchange for repeal of the nullification ordinance. Although most South Carolinians considered the Compromise of 1833 a success – their State had singlehandedly won a reduction in federal tariffs! – Smith strenuously objected, arguing that they were betraying their principles for a bribe. “The enemy is, for the moment, beaten back,” conceded Smith, though he cautioned that “the disease is still there,” and that “the true disorder is that pest of our system, consolidation.” Smith was particularly galled that the “angry tyrant,” President Jackson, had resorted to threats of “coercion” and “civil war,” and thus admitted that he no longer loved nor was loyal to the United States. “I cannot love, I will not praise that which, under the abused names of Union and Liberty, attempts to inflict upon us every thing that can curse and enslave the land.” According to Smith, the conflict between the North and the South was “a contest which even this compromise can but for a little while avert.”

In 1834, while serving as South Carolina’s Attorney General, Smith acquired four plantations and over a hundred slaves in a transaction with an English colonel forced to sell his holdings due to Britain’s abolition of slavery. Personally attached to his slaves and feeling responsible for their wellbeing, the colonel feared that in selling his slaves, they would be separated and perhaps come under cruel masters. The reason this colonel sold to Smith was because he trusted him to be a benevolent master. Indeed, Smith was a conscientious master who believed that slave ownership carried sacred duties. “I am responsible to God for their spiritual and temporal welfare…God helping me, I am determined that every soul he has committed to my care shall have the considerations of the Gospel brought home to its bearer, and whilst I administer to the necessities of these slaves in this world, the great and one thing needed for eternity shall not be neglected.” This transaction elevated Smith from a lawyer to a planter – from a profession to the aristocracy. Despite later financial difficulties, Smith kept his word to the colonel and never sold the slaves.

Smith was elected to the House of Representatives in 1836, where he served until 1848, doggedly defending the rights of the States – and especially those of South Carolina – from usurpation. It was at this point that he and his brothers changed their surname to “Rhett,” to honour a distinguished ancestor – a swashbuckling Colonial governor – and restore a historic name. Rhett endorsed President Van Buren’s Independent Treasury System (he was one of two South Carolinians who stood with Calhoun on this issue) and opposed the establishment of a third national bank, which he accused of causing the financial panics of 1819 and 1837, robbing Southern planters for the benefit of Northern bankers, and consolidating power in the federal government by giving it control of the money. Rhett also fought to destroy the American System once and for all, “that poison still lingering in the veins of the body politic – that unhallowed and corrupt combination by which one section of the Union was plundered for the benefit of another,” and to replace the inequitable tariff system with a more equitable system of direct taxation. Rhett opposed war with Britain over the Oregon Territory – denouncing all war as “an enormous crime” contrary to the peace, justice, and liberty on which Christian, conservative republics should be founded – though he wholeheartedly supported the Mexican War as a just war of self-defense. Slavery became an increasingly important issue during Rhett’s career in the House, beginning as a parliamentary dispute over whether the Congress had the right to receive abolition petitions, escalating with the question of admitting Texas to the Union, and ending as a debate over the legal status of slavery in the Territories. Underlying all of these issues was a struggle to maintain a balance of power between the North and the South. Rhett resisted these mounting encroachments upon slavery, claiming that the federal government had no authority over the South’s peculiar institution and thus could not receive any such petitions, that the South was entitled to the “common property of the States” as much as the North, and that any concession from the South would result in her enslavement to the North. “Here is a subject in which passion, and feeling, and religion, are all involved,” Rhett rued. “All the inexperienced emotions of the heart are against us; all the abstractions concerning human rights can be perverted against us; all the theories of political dreamers, atheistic utilitarians, self-exalting and self-righteous religionists, who would reform or expunge the Bible – in short, enthusiasts and fanatics of all sorts are against us.”

In 1844, disillusioned with the Democratic Party, angry over the Black Tariff (an increase in violation of the Compromise of 1833) and alarmed by Northern opposition to Texas statehood (a sign of Northern determination to limit the growth of the South), Rhett sparked the Blufton Movement. A revolution among the Lowcountry youth, the Blufton Movement called for another State convention, where an ultimatum of nullification or secession could be made, causing a crisis which would end with the restoration of the Constitution or the recognition of South Carolina’s independence. “They are raging,” Rhett said of the so-called Blufton Boys, “and if the rest of the South was of their temper we would soon bring the government straight both as to Texas and the tariff.” At a banquet in Blufton, Rhett raised a toast to the proposed convention: “May it be as useful as the Convention of 1776.” Rhett expected to be branded a “disunionist, mischief-maker, traitor, etc.,” but he dismissed such epithets as the propaganda of the timid and slavish souls against the bold and free. “My object is not to destroy the Union, but to maintain the Constitution, and the Union too, as the Constitution has made it,” explained Rhett. “But I do not believe that the government can be reformed by its central action, and that we will probably have to risk the Union itself to save it, in its integrity, and to perpetuate it as a blessing.” Although the Blufton Movement subsided when Calhoun obtained assurances of tariff reform and Texas statehood from the Democrat presidential candidate, James K. Polk, Rhett had succeeded in radicalizing the next generation of South Carolinians. “The Blufton Boys have been silenced, not subdued,” claimed Rhett. “The fire is not extinguished; it smolders beneath, and will burst forth in another glorious flame that shall overrun the State and place her light again as of old, upon the watchtower of freedom.”

After Calhoun’s death in 1850, Rhett was elected to fill his seat in the Senate. Rhett attended a convention of Southern States in Nashville in 1850, as well as a South Carolina convention in 1852. It was between the two conventions that Rhett renewed his calls for South Carolina to secede on her own, although this time the ultimatum was not to the United States to recognize Southern rights, but to the other Southern States to secede and form a confederacy of their own. “Separate State action,” insisted Rhett, would compel the “cooperation” of the rest of the South. “Cooperation,” he toasted at a celebration of the American Revolution, “our fathers obtained it by seizing the stamps, and by firing the guns of Fort Moultrie.” It was around this time when Southern Unionists began referring to Rhett and other secessionists as “Fire-Eaters,” a derogatory term for brash duelists. After a controversial speech at the Nashville Convention, where he remarked that Southerners “must rule themselves or perish,” Rhett was branded a “traitor.” Rhett reveled in the term, however. “I have been born of traitors, but thank God, they have ever been traitors in the great cause of liberty, fighting against tyranny and oppression,” boasted Rhett. “Such treason will ever be mine whilst true to my heritage.” Rhett’s constituents concurred, hoisting banners which read, “Oh that we were all such traitors,” and hailing Rhett as Patrick Henry reborn. When the South Carolina Convention closed with a resolution upholding the right of secession but taking no action herself – nothing more than “solemn and vapid truisms,” according to Rhett – Rhett felt that he was no longer a “proper representative” of South Carolina and resigned his Senate seat. “Sensible of the profound respect I owe the State as my sovereign, and deeply grateful for the many favors and honors she has conferred upon me, I bow to her declared will, and make way for those, who, with hearts less sad, and judgments more convinced, can better sustain her in the course she has determined to pursue.” Rhett spent the rest of the 1850s tending to his long-neglected plantations and rebuilding the Charleston Mercury, a newspaper which had always served as his mouthpiece and which his son had recently acquired.

After the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, Rhett believed that South Carolina had no choice but to secede from the Union. “The tea has been thrown overboard,” declared Rhett’s Mercury. “The revolution of 1860 has been initiated.” Rhett warned that the Republicans, a Northern sectional party, were “totally irresponsible to the people of the South, without check, restraint, or limitation,” and that their rule would bring “the total annihilation of all self-government or liberty in the South.” When South Carolina convened to secede, Rhett’s hour had finally come. “Rhett Guards” paraded through the streets of Charleston, carrying banners emblazoned with some of his finest words, and his image was displayed alongside the great Calhoun’s. Elected to represent his old district in the Secession Convention, Rhett fell to his knees in prayer before signing South Carolina’s ordinance of secession. “For thirty-two years, have I followed the quarry. Behold! It, at last, in sight!” exclaimed Rhett. “A few more bounds, and it falls – the Union falls; and with it falls, its faithless oppressions – its insulting agitations – its vulgar tyrannies and fanaticism. The bugle blast of our victory and redemption is on the wind; and the South will be safe and free.”

Rhett’s moment of triumph flamed out almost immediately, however. Rhett was the head of the South Carolina delegation to the Montgomery Convention, where the Confederate States framed a new constitution, a task which Rhett believed should be “a matter of restoration” rather than “innovation,” as the old Constitution was not flawed, but simply perverted by Northern construction. Although Rhett obtained prohibitions on the long-detested protectionist tariffs and internal improvements, along with express affirmations of the long-defended principle of State sovereignty, he failed to prevent the admission of non-slaveholding States, which he feared would lead to reconstruction with the North and ultimately recreate all the problems of the old Union – a Northern majority with different values and interests tyrannizing a Southern minority. Furthermore, in forming a provisional government, the conservatives at Montgomery like Jefferson Davis prevailed over the radicals like Rhett – a “Thermidor” which left Rhett embittered and envious. Rhett became a maniacal critic of President Davis, accusing him of assuming the powers of a military despot – worse than Lincoln, in fact! – and betraying the Confederacy. As Mary Chesnut, the South Carolina diarist who described Rhett as “mercurial,” explained, Rhett “had howled nullification, secession, etc. so long, when he found his ideas taken up by all the Confederate world, he felt he had a vested right to the leadership.”

When Lincoln summoned troops to crush what he dismissed as a rebellion, Rhett’s Foreign Affairs Committee was responsible for drafting a declaration of war against the United States. To accompany the declaration of war, Rhett prepared a report presenting the cause and character of the conflict to the world. “It was plain that it might be no easy task, to make European nations understand the true nature of the contest,” admitted Rhett. “The rights of the Southern people under the terms of the Constitution, were unfortunately implicated with African slavery; and it might appear to European nations, that not the principle of free government, but the perpetuation of African slavery, was the real issue in the contest.” Rhett, therefore, sought to set the record straight. “The real issue involved in the relations between the North and the South of the American States, is the great principle of self-government,” explained Rhett. “Shall a dominant party of the North rule the South, or shall the people of the South rule themselves?” According to Rhett, after “long forbearance and patience,” stemming from a “heroic love for the Union” over “mere interest,” the South was driven to secede from the Union in order to escape the “ruthless mastery” of the North,” which was now threatening “to subject them by the sword.” Aside from this report, Rhett contributed little to nothing to the Confederate government, seemingly fixated with thwarting President Davis at every turn. When elections were held, Rhett did not run for office, but returned home and continued his opposition to “King Davis” and “the piddling, prostrate Congress,” from the pages of the Mercury.

The hard hand of war fell heavily on Rhett. Two of his sons died in the Confederate army. One of his daughters, unable to cope with her husband’s death, drank herself to death. General William T. Sherman’s army plundered his plantations, scattering his personal papers and stealing his books. Perhaps Rhett’s sole consolation was the loyalty of his slaves, who fled with their refugee-master and worked his land in exchange for a share of the crop even after they were emancipated. Unable to meet his debts after the war, what was left of Rhett’s estate eventually went into foreclosure. Rhett closed out his years living with one of his daughters in New Orleans, suffering from skin cancer and toiling on his memoirs, tentatively titled, The Last Decade, Seen in the Extinction of Free Government in the United States, and the Downfall of the Southern Confederacy, in Connection with Political Life and Services of the Honorable Robert Barnwell Rhett. Defiant to the end, Rhett rejected any reconciliation with the North and remained confident that the South would one day rise again. “Whether sitting around their hearths; or worshipping in the Temples of God; or standing over the graves of our Confederate dead,” proclaimed Rhett, “they will ever remember that they died for them; and spurn from them, as an imputation of the foulest dishonor, the mere suggestion that they can ever abandon their great cause – the cause of free government for which their glorious dead suffered and died.” Upon Rhett’s death in 1876, The Charleston News and Courier dubbed him “the father of secession.”

Outside of South Carolina, Rhett was widely detested, and even within South Carolina, Rhett was a controversial figure who could never lead, but only incite and electrify. According to historian Walter Brian Cisco, “Two generations of South Carolinians would come to grin or grimace at the mention of his name.” Indeed, it was Rhett’s repulsive public persona, rather than his ideas – visionary in their time and vindicated in the end – which made him so unpopular. Rhett’s rival, James H. Hammond, compared him to Cassandra, the mythological Greek priestess blessed with the gift of foresight but cursed for her warnings to go unheeded. “How unfortunate that Cassandra came to preside over his birth & make him say the wisest things, so out of time and place, that they are accounted by those who rule mere foolishness,” reflected Hammond. “What a pity that such fine talents should be thrown away on such a perverse temper.” According to Rhett’s biographer, Laura A. White, “It may be said that one can scarcely understand the action of the people of South Carolina in 1860 without including in his ken the remarkable activities of one man, whose eloquent and fiery preaching of the gospel of liberty and self-government, and of revolution to achieve these ends, beat upon their ears in season and out of season for over thirty years.”

During the South Carolina Secession Convention there was a dispute over how the State should justify secession. Maxcy Gregg, a friend of Rhett’s and fellow Fire-Eater, objected that Christopher Memminger’s Declaration of the Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union focused only on relatively recent grievances related to slavery and thus “dishonored the memory of South Carolinians” who had opposed the Tariff of Abominations, the Second Bank of the United States, and internal improvements. Laurence M. Keitt, another Fire-Eater, though no friend of Rhett’s, replied that while tariffs were now low, no national bank existed, and internal improvements were regularly vetoed, “the question of slavery” remained unresolved. As a result, South Carolina issued two statements on secession: Memminger’s narrow, legalistic Declaration – the title of which was amended to read “immediate causes” – and Rhett’s Address of South Carolina to the Slaveholding States, a fiery manifesto of Southern rights and Northern wrongs. Historian Emory M. Thomas describes the Address as “an extended dissertation which began with the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and rambled through a long catalogue of sectional issues and crises, demonstrating Southern righteousness and Yankee perfidy at every point.” Susan Bradford, a fourteen year-old girl whose father took her to Florida’s Secession Convention in Tallahassee, remembered an ambassador from South Carolina reading the Address –“recounting the grievances, which had led her to sever the ties which bound her to the Union” – to the convention. “You never heard such cheers and shouts as rent the air, and it lasted so long.”

From the adoption of the Constitution in 1787 to the secession of South Carolina in 1860, opened Rhett, the United States’ “advance in wealth, prosperity, and power, has been with scarcely a parallel in the history of the world.” The “great object” of forming the Union was “defense against external aggressions,” which had been amply secured. The United States was safe and free, and Northern ships sailed every sea exporting Southern cash crops around the world. Despite its outward strength, however, the Union was imploding from “discontent and contention.” In short, admitted Rhett, “Our internal peace has not grown with our external prosperity.”

Twice in the past three decades – 1832 and 1852 – South Carolina had convened to react to “the aggressions and unconstitutional wrongs, perpetrated by the people of the North on the people of the South.” Both times, South Carolina had agreed to a compromise, believing that it would resolve the conflict between the sections and restore harmony to the Union. “But such hope and expectation, have proved to be vain,” claimed Rhett. “Instead of producing forbearance, our acquiescence has only instigated new forms of aggression and outrage; and South Carolina, having again assembling her people in Convention, has this day dissolved her connection with the States, constituting the United States.” The dissolution of the Union, long-feared but long-expected, had finally come to pass.

According to Rhett, “The one great evil, from which all other evils have flowed, is the overthrow of the Constitution of the United States.” The federal government was no longer “the government of Confederated Republics,” as it was founded, but “a consolidated Democracy.” Such a government was “no longer a free Government, but a despotism.” In fact, the federal government had become the same form of government that “Great Britain attempted to set over our fathers; and which was resisted and defeated by a seven years’ struggle for independence.” Throughout the Address, Rhett continued to draw parallels between the past of 1776 and the present of 1860, deservedly draping South Carolina in the mantle of the American Revolution.

“The Revolution of 1776 turned upon one great principle,” claimed Rhett, “self-government – and self-taxation, the criterion of self-government.” In order to be free, explained Rhett, different people who were united under a common government must have the power to protect their separate and distinct interests, yet the interests of Britain and the American Colonies had become “different and antagonistic.” Britain’s policy towards the Colonies was to exploit them as she did the rest of her empire, “making them tributary to her wealth and power.” Britain had accumulated a high debt from her wars around the world, and intended to recoup the costs of empire from her Colonies. The Colonies, however, opposed British mercantilism and imperialism, desiring freedom from the “burdens and wars of the mother country.” After all, the Colonies’ charters granted them the right of self-government, especially regarding the vital issue of taxation. These conflicting interests culminated in the Parliament’s infamous assertion of supremacy over the Colonies – “the power of legislating for the Colonies in all cases whatsoever.” Such a usurpation of their chartered rights drove the Colonies to independence. “Our ancestors resisted the pretension,” beamed Rhett. “They refused to be a part of the consolidated Government of Great Britain.”

Rhett stressed that the same causes that justified American secession in 1776 also justified Southern secession in 1860. Indeed, “The Southern States now stand exactly in the same position towards the Northern States that the Colonies did towards Great Britain.” Like Britain, the Northern States defied the Constitution and claimed “omnipotence in legislation.” Like Britain, the Northern States recognized no constitutional limits upon their power except for the “the general welfare,” of which they were the “sole judges.” As Britain had infamously asserted against the Colonies, the North claimed the power to legislate for the South “in all cases whatsoever.” The Union no longer resembled what the Founding Fathers had shaped, leaving their sons no choice but to follow in the footsteps of their forefathers and declare their independence. “Thus, the Government of the United States has become a consolidated Government; and the people of the Southern States are compelled to meet the very despotism their fathers threw off in the Revolution of 1776.” According to Rhett, in declaring independence from tyranny as the Founding Fathers had done, Southerners were the true Americans.

As a part of its consolidation of power over the Colonies, the Parliament levied taxes to enrich British interests at the expense of American interests. The Colonies resisted these taxes, however, arguing that their charters granted them the right of self-government and thus self-taxation. The Colonies were represented only in their own legislatures, not in the Parliament, meaning the Parliament had no constitutional authority to tax them. Even when the Colonies were offered representation in Parliament, they refused to sacrifice their chartered right of local self-government for a little representation in a foreign legislature. “Between taxation without any representation, and taxation without a representation adequate to protection, there was no difference,” explained Rhett. “In neither case would the Colonies tax themselves. Hence, they refused to pay the taxes laid by the British Parliament.” The particular issue in 1776 was self-taxation – no taxation without representation! – but the principle was self-government. Rhett would return to this differentiation between the outer issues and underlying causes of a conflict in arguing that secession was about more than just slavery.

Just as Britain attempted to consolidate its power over the Colonies by taxing them without representation – thereby depriving them of their right of self-government – so the North was attempting to use “the vital matter of taxation” to consolidate her power over the South and rule her as well. Since the Southern States had become a minority in the United States, their representation in the Congress was powerless to prevent “unjust taxation” in the form of protectionist tariffs. Indeed, for over forty years, “subserving the interests of the North,” rather than collecting revenue, had been the agenda behind federal taxes. Since the South was an agrarian economy which exported most of her production (cash crops like cotton, tobacco, and rice) and imported most of her consumption (manufactures from machinery to textiles), her economic interest was in free trade. The industrial Northern economy, however, had no strong comparative advantages in anything and depended on the federal government for support. Tariffs, by taxing the imports on which the South relied, protected Northern industries from competition but imposed artificially inflated the prices upon the South. The South was forced to buy the manufactures she needed in a protected market (choosing between higher prices to parasitic Northern industries or higher taxes to a government which no longer represented them) and sell the cash crops she produced in a competitive market – to buy dearly and sell nearly, so to speak. At the same time, by reducing American demand for foreign imports and foreign currency, tariffs also depressed foreign demand for American exports (in this case, 60% to 90% of which were Southern cash crops) and distorted the exchange rate in a way which left exporters with less. “They are taxed by the people of the North for their benefit,” Rhett said of Southerners, “exactly as the people of Great Britain taxed our ancestors in the British Parliament for their benefit.”

“There is another evil, in the condition of the Southern towards the Northern States,” continued Rhett, “which our ancestors refused to bear towards Great Britain.” Each Colony not only taxed herself, but also spent the taxes she collected on herself. If the Colonies had submitted to taxation without representation, then their taxes would have been spent throughout the British Empire rather than at home. Although this redistribution – “impoverishing the people from whom taxes are collected, and…enriching those who receive the benefit of the expenditure” – was resisted by the Colonies, the North had, as with oppressive taxation, succeeded against the South where Britain had failed. Federal tax revenue, collected primarily from the South, often financed so-called internal improvements in the North, which ranged from honest economic development to the nineteenth-century equivalent of pork-barrel spending. Either way, Southerners saw their property drained across the Mason-Dixon Line. “The people of the Southern States are not only taxed for the benefit of the Northern States, but after the taxes are collected, three-fourths of them are expended at the North.”

This exploitative scheme of taxing the South and spending in the North had, argued Rhett, left the South “provincial” and “paralyzed” her growth. One of many indicators was the decline of South Carolina’s shipping, an industry that had prospered in the Colony but had been “annihilated” in the Union due to navigation laws which gave the North a legal monopoly on shipbuilding and shipping. To prove his point, Rhett cited figures contrasting the prosperity of the Colony of South Carolina with the poverty of the State of South Carolina.

“No man can, for a moment,” concluded Rhett, “believe that our ancestors intended to establish over their posterity, exactly the same sort of Government they had overthrown.” Indeed, the “great object” of the Constitution was “to secure the great end of the Revolution – a limited free government.” Under the Constitution, “general and common” interests were delegated by the States to the federal government, and “sectional and local” interests were reserved by the States. This division of power between the national and the sectional was the only way to unite separate, distinct sections with differing interests such as the North and the South. Unfortunately, Northern treachery and Southern complacency had resulted in the erosion of limited government. “By gradual and steady encroachments on the part of the people of the North, and acquiescence on the part of the South, the limitations in the Constitution have been swept away,” recounted Rhett. “The Government of the United States has become consolidated, with a claim of limitless powers in its operations.”

To Rhett, “agitations” against slavery were merely the “natural results of the consolidation of the government.” Since the North, with her “interested and perverted” construction of the Constitution, had exceeded national interests and was encroaching upon sectional interests, it was inevitable that she would eventually “assume to possess power over all the institutions of the country” and “assail and overthrow the institution of slavery in the South.” Slavery, furthermore, was the only issue against which the North could be united. “It would not be united, on any matter common to the whole Union – in other words, on any constitutional subject – for on such subjects divisions are as likely to exist in the North as in the South.” Because slavery was a “strictly sectional interest” of the South, opposition to it overcame the differences of opinion in the North over the proper construction of the Constitution. “If this could be made the criterion of parties at the North, the North could be united in its power,” explained Rhett, “and thus carry out its measures of sectional ambition, encroachment, and aggrandizement.” Indeed, this had been a tactic of the North since the Missouri Crisis, when the Federalist Party challenged the admission of slaveholding Missouri to the Union in the hopes of restricting Southern political power and reclaiming the North on a new sectional issue. “To build up their sectional predominance in the Union, the Constitution must first be abolished by construction,” argued Rhett, “but that being done, the consolidation of the North, to rule the South by the tariff and slavery issues, was in the obvious course of things.”

Rhett distinguished between the ultimate cause of the conflict between the North and the South, “the overthrow of the Constitution” and “the consolidation of the government,” and the particular issues which had stemmed from the cause, such as tariffs and slavery. As Rhett put it, the North wanted “to rule the South by the tariff and slavery issues,” just as Britain wanted to rule the Colonies through “the vital matter of taxation.” In other words, the cause of the conflict was the Northern pretension to rule the South; the issues of tariffs and slavery were merely means to that end. After the war, Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stephens, and countless other former Confederates reiterated the Father of Secession’s formulation in their unapologetic apologias. According to Davis, slavery was “in no wise the cause of the conflict, but only an incident,” the “intolerable grievance” being “the systematic and persistent struggle to deprive the Southern States of equality in the Union.” According to Stephens, slavery was “unquestionably the occasion of the war…but it was not the real cause, the Causa causans of it,” the real cause being “Federation, on the one side, and Consolidation, on the other.” For differentiating between outer issues and underlying causes, as Rhett himself did on behalf of South Carolina, Davis and Stephens are commonly accused of revising history.

The Constitution, Rhett reflected, was an “experiment…in uniting under one government, peoples living in different climates, and having different pursuits and institutions.” In such a constitution, trust between the States was paramount, for the Constitution could not limit itself and would ultimately be interpreted and enforced by the States. “It matters not how carefully the limitations of such a government be laid down in the Constitution – its success must, at least, depend upon the good faith of the parties to the constitutional compact, in enforcing them.” No matter how strictly the Constitution was written, well-meaning errors and self-serving rationalizations would inevitably arise. “It is not in the power of human language to exclude false inferences, constructions, and perversions in any Constitution,” admitted Rhett. “And when vast sectional interests are to be subserved, involving the appropriation of countless millions of money, it has not been the usual experience of mankind, that words on parchment can arrest power.” The experiment of the Constitution, argued Rhett, “rested on the assumption that power would yield to faith – that integrity would be stronger than interest; and that thus, the limitations of the Constitution would be observed.” The experiment, though “fairly made,” had finally “failed.”

From the very beginning, the South had tried to limit the federal government “within the orbit prescribed by the Constitution.” Indeed, from when Senator Pierce Butler, a framer in Philadelphia and a ratifier in Charleston, stormed out of the very first Senate in protest of a proposed protectionist tariff and threatened the secession of South Carolina, to the actual secession of South Carolina, the South had always honoured the compact. The North, however, had not honoured the compact, committing usurpations and encroachments at every opportunity. In a “reckless lust for power,” the North had “absorbed” the entire Constitution into its preamble, claiming that the United States was a nation with a consolidated government rather than a federation with a limited government. The irony of this sophistic and solipsistic Northern construction, noted Rhett, was that in attempting to make the federal government stronger, it actually made it weaker. The federal government was intended to have authority only over “objects of common interests to all sections.” This, insisted Rhett, was where its “strength consists.” If the “scope” of its power were expanded over “sectional or local interests,” however, it would necessarily face “opposition and resistance” – the very sort of opposition and resistance which Rhett had led his whole life and which had finally come to a head. Expanding federal power from national interests – the true meaning of the “general welfare” – to sectional interests meant that the minority would not possess the power of self-protection against a potentially tyrannous majority, and thus “necessarily” turned the government into a “despotism.” Rhett warned that “the majority, constituted from those who do not represent these sectional or local interests, will control and govern them,” and urged that “a free people cannot submit to such a Government.” As federal power expanded beyond its rightful sphere, opposition and resistance weakened the legitimacy of the government. The key to a strong Union was not for the majority section to tyrannize the minority, but for both sections to cooperate for the common good and respect each other’s differences. “The more it abstains from usurped powers, and the more faithfully it adheres to the limitations of the Constitution, the stronger it is made,” explained Rhett. “The Northern people have had neither the wisdom nor the faith to perceive, that to observe the limitations of the Constitution was the only way to its perpetuity.” In other words, if the purposes for which the Union was founded, as established in the Constitution, were no longer upheld, then the Union no longer served any purpose and was not worth upholding.

Under a consolidated government of unlimited power, conflicts would inevitably arise between differing sections, noted Rhett, and the North and the South were no exception. “Under such a government, there must, of course, be many and endless ‘irrepressible conflicts’ between the two great sections of the Union,” explained Rhett, employing the expression of the Republican luminary William H. Seward. Having weakened limited government with liberal constructions of the Constitution, the Northern majority was poised to exploit the Southern economy, subvert Southern society, and consolidate all power over the South. Only the goodwill upon which the States created the Union could protect the liberty and security of the South, yet South Carolinians regarded Northerners as treacherous and untrustworthy. “The same faithlessness which has abolished the Constitution of the United States, will not fail to carry out the sectional purposes for which it has been abolished.” Given that “all confidence in the North is lost by the South,” Rhett claimed that it was “too late to reform or restore” the Union. “The faithlessness of the North for half a century has opened a gulf of separation between the North and the South which no promises nor engagements can fill.” Therefore, due to the destruction of the Constitution, the abandonment of the good faith necessary to sustain a compact, and an imbalance of power between the sections of the Union, the South’s only hope for “peace and liberty” was in “independence of the North.”

Like all Southerners –especially South Carolinians – Rhett was extremely sensitive about the honour of his State, which had acquired a reputation for extremism over the years. The Address was a prime opportunity for Rhett to redeem South Carolina and her uncompromising course in the eyes of her Southern sisters. Indeed, South Carolina had staunchly defended States’ rights and resisted Northern consolidation for the past thirty years, yet had been abandoned by the rest of the South and condemned by the North. “The repeated efforts made by South Carolina, in a wise conservatism, to arrest the progress of the General Government in its fatal progress to consolidation, have been unsupported, and she has been denounced as faithless to the obligations of the Constitution, by the very men and States who were destroying it by their usurpations,” stewed Rhett. Given his role in those repeated efforts, Rhett could not have helped feeling some sense of satisfaction.

“It cannot be believed, that our ancestors would have assented to any union whatever with the people of the North, if the feelings and opinions now existing among them, had existed when the Constitution was formed,” speculated Rhett. “There was then no tariff – no fanaticism concerning negroes.” Indeed, Founders like John Rutledge and Charles Pinckney, who had framed the Constitution in Philadelphia and ratified it in Charleston, had assured skeptical South Carolinians that the new Constitution did not contain any of those evils. “The idea that the Southern States would be made to pay that tribute to their Northern confederates which they had refused to pay to Great Britain; or that the institution of African slavery would be made the grand basis of a sectional organization of the North to rule the South, never crossed the imaginations of our ancestors.” Rhett pointed out that the Constitution was founded on slavery, as slavery then existed in the Southern, Middle, and Northern States, the slave trade was extended for twenty years, and three-fifths of all slaves in each State were counted in assessing federal representation and apportioning federal taxes. “There is nothing in the proceedings of the Constitution, to show that the Southern States would have formed any other Union; and still less, that they would have formed a Union with more powerful non-slaveholding States, having majority in both branches of the Legislature of the Government.”

Since the adoption of the Constitution, however, the North and the South had separated politically, economically, and culturally; the Union formed by the Founders was no more. “That identity of feelings, interests, and institutions which once existed is gone,” explained Rhett. “They are now divided, between agricultural, manufacturing, and commercial States; between slaveholding and non-slaveholding States.” Given these changes, the North and the South had become “totally different peoples,” making “equality between the sections” impossible. “We but imitate the policy of our fathers in dissolving a union with non-slaveholding confederates, and seeking a confederation with slaveholding States.”

Rhett believed that the liberty and security of a society could only be preserved by that society itself. Outside of that society, such power would be perverted and abused. “No people can ever expect to preserve its rights and liberties, unless these be in its own custody,” claimed Rhett. “To plunder and oppress, when plunder and oppression can be protected with impunity, seems to be the natural order of things.” Accordingly, argued Rhett, “Experience has proved that slaveholding States cannot be safe in a subjection to non-slaveholding States.” Rhett pointed out that the British colonies of the West Indies and the French colony of Santo Domingo, where radical abolitionism was tried, had collapsed into poverty and savagery. “The fairest portions of the world…have been turned into wildernesses, and the most civilized and prosperous communities have been impoverished and ruined by anti-slavery fanaticism.” The fate of Santo Domingo was particularly terrifying to Southerners. When the National Assembly, in the throes of the French Revolution, decreed “liberty, equality, and fraternity” for the slaves, the freed slaves seceded from the empire, wiped out the white population, and repelled Napoleon’s efforts to reclaim the colony. Now the North was threatening the South with the same fate as Santo Domingo.

Rhett claimed that the sectional Republican Party had made its intentions against Southern slavery perfectly clear – particularly in the nomination of Abraham Lincoln. “United as a section in the late Presidential election, they have elected as the exponent of their party, one who has openly declared that all the States of the United States must be made free States or slave States.” Rhett conceded that there were “various shades of anti-slavery hostility” and a multitude of “disclaimers and professions” from the Republicans. Lincoln himself equivocated on the issue depending upon his audiences, telling Northerners that a house divided against itself cannot stand and that the United States could not be half-slave and half-free, but telling Southerners that he had no authority or intention to abolish slavery but just wanted to keep the Territories free for whites and unsullied by blacks. Rhett emphasized, however, that the “inexorable logic” of Republicans’ position would eventually end in abolition. “If it is right to preclude or abolish slavery in a Territory,” asked Rhett, “why should it be allowed to remain in the States?” Since the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision ruled that the Congress had no constitutional authority to prohibit slavery in the Territories, prohibiting slavery in the Territories was just as unconstitutional as prohibiting slavery in the States. “When it is considered that the Northern States will soon have the power to make that Court what they please, and that the Constitution never has been any barrier whatever to their exercise of power, what check can there be, in the unrestrained counsels of the North, to emancipation?”

Today, with slavery 150 years dead, Rhett’s staunch support for the institution must seem repulsive. Slavery was indeed a repulsive institution, yet there are several reasons why Rhett and his fellow slaveholders should be viewed with more sympathy.

First and foremost is the basic historical maxim that the past should be judged juxta propria principia, or “according to its own principles.” By the standards of Rhett’s time, slavery had existed throughout all of human history – including the esteemed classical civilizations of Greece and Rome – and in the New World for over 300 years. In the Bible, slavery was sanctioned by the Law and accepted by the Gospel. Under the Constitution, slavery was a clearly protected right of the States, no power over slavery having been delegated to the federal government. To Southerners like Rhett, slavery was not an abomination as we see it today, but had been a cornerstone of the American way of life from the time of the Colonies. It was the plantation, after all, that fathered many of the Founders – men such as George Washington (the Father of His Country), Thomas Jefferson (the Father of Democracy), James Madison (the Father of the Constitution), George Mason (the Father of the Bill of Rights), and many more noble members of America’s original ruling class. In contrast to this tradition, Northerners – with a party platform designed to squeeze every penny of profit out of federal policy, a proletariat with a lower standard of living than that of the slaves, and no real knowledge of or interest in the South – condemned Southerners as criminals and sinners and demanded that they perform the vastest self-disinheritance in history, with nothing but the dire, dismal Santo Domingo and West Indies as precedents.

The second reason that Rhett should be viewed with sympathy is that slavery itself was, as the old Vanderbilt Agrarian John Crowe Ransom observed in I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, “monstrous enough in theory, but more often than not, humane in practice.” Scholars such as Ulrich B. Phillips and Eugene D. Genovese have found that slavery was not simply a cruel regime of exploitation, but as the slaveholders themselves maintained, a paternalistic institution in which masters and slaves formed one “family” with mutual rights and duties. This is not to romanticize slavery, which Phillips and Genovese – and perhaps Rhett himself, who once interceded to stop the brutal whipping of a slave – would be the first to admit had a dark side, but simply to reflect on slavery rationally, without the distortion of emotions such as hatred or shame.

Last, but not least, Rhett should be viewed with sympathy because his political philosophy – which, in these times of majoritarian democracy and an unchecked, uncontrollable central government, is needed more than ever – can be separated from his support for slavery. As proof of the sincerity of his beliefs, Rhett raised the banner of States’ rights in the midst of the Tariff Crisis, years before slavery became a national issue, and continued to wave it long after slavery had been abolished. In sum, Rhett should be viewed not from our present looking backward, but from his present looking forward. This is the only way to understand the past – anything else is the historian’s sin of “presentism,” or what Christian intellectual C.S. Lewis called “chronological snobbery.”

Slavery was certainly not the sole cause of conflict between the North and the South, noted Rhett. In addition to economic issues like the tariff and internal improvements, the North and the South clashed over opposing political philosophies. “Not only their fanaticism, but their erroneous ideas of the principles of free governments, made it doubtful whether, if separated from the South, they can maintain a free government amongst themselves.” According to Rhett, the North had abandoned republicanism and had embraced egalitarianism. “Numbers, with them, is the great element of free government,” explained Rhett. “A majority is infallible and omnipotent.” The whole purpose of constitutions, however, was to limit the power of the majority and protect the liberty and security of the minority. “The very object of all Constitutions, in free popular government,” argued Rhett, “is to restrain the majority.” To the egalitarian North, therefore, constitutions were not blessings to be upheld, but “unrighteous inventions” which limited the “will of the majority.” In a single, small society with “identity of interests and pursuits,” like an ancient Greek city-state, the absence of a constitution was “harmless,” as there was unanimity among the polity. In a larger society, however, such as an American State, and especially in a “vast Confederacy” such as the United States, “various and conflicting interests and pursuits” necessitated a constitution; otherwise, the government would be a “remorseless despotism” of the majority over the minority.

Rhett declared that it was such a majoritarian despotism from which South Carolina was seceding. “We are vindicating the great cause of free government, more important, perhaps, to the world, than the existence of all the United States.” Secession, Rhett insisted, was but a peaceful dissolution of bonds between sovereignties – a declaration of independence, not a declaration of war. “In separating from them, we invade no rights – no interest of theirs,” stressed Rhett. “We violate no obligation or duty to them.” Indeed, in seceding from the Union South Carolina was doing nothing more than repealing the ratification ordinance of a constitution which she helped frame and by which she originally acceded to the Union. “As separate, independent States in Convention, we made the Constitution of the United States with them; and as separate, independent States, each State acting for itself, we adopted it,” explained Rhett. “South Carolina, acting in her sovereign capacity, now thinks proper to secede from the Union.” Rhett denied that the States sacrificed their sovereignty to the Union. “She did not part with her sovereignty in adopting the Constitution.” Since sovereignty was a State’s “life,” it was “the last thing a State can be pressured to surrender.” Even then, such a serious sacrifice could not be signified by mere “inference,” as the North interpreted the Preamble, but by nothing less than a “clear and express grant.” Rhett scorned this Northern attempt to construe away the cornerstone of the Constitution and sighed at the Northerners’ predictability. “It is not at all surprising that those who have construed away all the limitations of the Constitution, should also by construction, claim the annihilation of the sovereignty of the States,” Rhett sneered. “Having abolished all barriers to their omnipotence, by their faithless constructions in the operations of the general government, it is most natural that they should endeavor to do the same towards us in the States.”

All told, concluded Rhett, the North had violated the Constitution so pervasively that it was no longer a “compact” at all, and certainly no longer “morally obligatory” upon the States. According to Rhett, the North, by breaking the trust of the compact, was the true disunionist section. “South Carolina,” stated Rhett, “deeming the compact not only violated in particular features, but entirely abolished by her Northern confederates, withdraws herself as a party from its obligations.” Yet the North, noted Rhett, seeing an opportunity to consummate her longstanding lust for dominion over the Union, was refusing South Carolina this basic right – the freedom to leave. “They desire to establish a sectional despotism, not only omnipotent in Congress, but omnipotent over the States,” raged Rhett, “and as if to manifest the imperious necessity of our secession, they threaten us with the sword, to coerce submission to their rule.”

Aware of South Carolina’s reputation even among other Southern States as an extremist, Rhett defended her conduct and called for Southern unity. South Carolina did not wish to be the first State to secede, assured Rhett, but felt that the decision had been forced upon her – what choice did she have, in the face of Northern consolidation? “Circumstances beyond our control have placed us in the van of the great controversy between the Northern and Southern States.” South Carolina had no ambition to rule a new Southern Confederacy, either. “Independent ourselves, we disclaim any design or desire to lead the counsels of other Southern States.” The Southern States, the seals of which were emblazoned upon the Secession Banner hanging in the hall where South Carolina had convened, belonged together. “Providence has cast our lot together, by extending over us an identity of pursuits, interests, and institutions,” urged Rhett. “South Carolina desires no destiny separated from yours.”

Hoping to stir South Carolina’s sisters to her cause, Rhett ended his Address with a Southern call to arms. It was Southern statesmanship and Southern valour which had always strengthened and secured the Union. “In the field, as in the cabinet, you have led the way to renown and grandeur.” The South had always honoured the Union, doing her duty even when it came with costs. “You have loved the Union, in whose service your great statesmen have labored, and your great soldiers have fought and conquered – not for the material benefits it conferred, but with the faith of a generous and devoted chivalry.” In spite of Northern treachery, the South had always remained loyal to the Union. “You have long lingered in hope over the shattered remains of a broken Constitution,” Rhett seethed. “Compromise after compromise, formed by your concessions, has been trampled underfoot by your Northern confederates.” With the triumph of a sectional Northern party within the Union, determined to consolidate its power and rule the South, Southern patience and benevolence was exhausted. “All fraternity of feeling between the North and the South is lost, or has been converted into hate,” announced Rhett. “We, of the South, are at last driven together by the stern destiny which controls the existence of nations.” If there were a silver lining to the South’s “bitter experience of the faithlessness and rapacity” of the North, it was that the conflict had forced the South “to evolve those great principles of free government, on which the world depend,” and prepared her “for the grand mission of vindicating and reestablishing them.”

Rhett denied that Southerners had any reason to apologize for their agrarian, slaveholding society, which he argued was superior to industrial, capitalist society. “We rejoice that other nations are satisfied with their institutions,” offered Rhett. “We are satisfied with ours.” According to Rhett, the North was infected with class conflict, poverty, and violence. “If they prefer a system of industry, in which capital and labor are in perpetual conflict – and chronic starvation keeps down the natural increase of population – and a man is worked out in eight years – and the law ordains that children shall be worked only ten hours a day – and the sabre and bayonet are the instruments of order – be it so,” shrugged Rhett. “It is their affair, not ours.” By contrast, in the South, unity, prosperity, and peace prevailed. “We prefer, however, our system of industry, by which labor and capital are identified in interest, and capital, therefore, protects labor – by which our population doubles every twenty years – by which starvation is unknown, and abundance crowns the land – by which order is preserved by an unpaid police, and many fertile regions of the world, where the white man cannot labor, are brought into usefulness by the labor of the African, and the whole world is blessed by our productions,” boasted Rhett. “All we demand of other people is to be left alone, to work out our own high destinies.” Southerners like Rhett sincerely believed that the paternalistic institution of slavery, by which capital provided for labor, was the alternative to the class conflict and collectivism which had consumed Europe and was sweeping the United States.

Rhett finished by painting a picture of the bright future of an independent, united South:

“United together…we must be the most independent, as we are among the most important, of the nations of the world. United together…we require no other instrument to conquer peace, than our beneficent productions. United together…we must be a great, free, and prosperous people, whose renown must spread throughout the civilized world, and pass down, we trust, to the remotest ages.”

Six years after Rhett’s death, the First South Carolina Volunteers, the former command of fellow Fire-Eater Maxcy Gregg, held a reunion in Barnwell Country. Colonel Edward McCrady, Jr., a respected historian and lawyer from Charleston, addressed what remained of the regiment. As Confederate veterans faded away, urged McCrady, those few left behind should unite and commemorate the sacrifices they made “for the cause which we maintain to have been righteous – even though lost.” At the same time, however, Confederate veterans should also transmit the truth to posterity – “tell to those who are growing up around us what were the great causes which impelled the young and the old of that time, the rich and the poor, the learned and the ignorant, to take up arms and risk their lives in battle.” As Rhett had always insisted, McCrady denied that slavery was the cause of the conflict between the North and the South, but merely an issue of a much deeper conflict. “We did not fight for slavery,” insisted McCrady, who explained that slavery “was not the cause of the war, but the incident upon which the differences between the North and the South, and from which differences the war was inevitable from the foundation of our government, did but turn.” Again in accordance with Rhett, McCrady maintained that States’ rights were the root cause of the conflict. “We fought for States’ rights and States’ sovereignty as a political principle,” declared McCrady. “We fought for the State of South Carolina, with a loyal love that no personal sovereign has ever aroused.” If slavery had never existed in America, continued McCrady, the North and the South would still have gone to war, for the “seeds” of the conflict were planted in the Constitution itself, growing from the opposing interpretations of Jefferson’s “Federal Party” and Hamilton’s “National Party.” As McCrady put it, “The Convention which framed the Constitution was itself divided into the two parties which, after seventy years of discussion…adjourned the debate to the battlefields of our late war.” Like Rhett, McCrady believed that the battle lines of the war were drawn when the President and the Congress threatened South Carolina with invasion for nullifying the Tariff of Abominations. In 1832 and 1860, explained McCrady, the “incident” differed – the tariff and slavery, respectively – but the underlying “question” of “the sovereignty of the State” remained the same. “Would that we might have fought and shed our blood upon the dry question of the tariff and taxation,” bemoaned McCrady, “instead of one upon which the world had gone mad.”

McCrady believed that the South Carolina Secession Convention was mistaken to have centered its Declaration solely on grievances related to slavery, as did Rhett. “It is a matter of satisfaction to us, my comrades,” remarked McCrady, “that our first and beloved commander, General Gregg, as a member of the Convention, opposed the adoption of the declaration on this very ground.” McCrady claimed that Rhett’s Address – “in which was so ably and well shown that the issue was the same as that in the Revolution of 1776, and like that turned upon the one great principle, self-government, and self-taxation, the criterion of self-government” – was a vastly superior “justification of the secession of the State.” According to McCrady, Rhett’s Address demonstrated that the South faced the same threats from the North that all Americans had once faced from the British – a majority with “omnipotence in legislation” judging the extent of the limitations on its own power – and thus that “the government of the United States had become a consolidated government, and the people of the Southern States were compelled to meet the very despotism their fathers threw off in 1776.”

McCrady’s speech at the Confederate reunion was a testament to the power of Rhett’s ideas, specifically how they had shaped the course of States’ rights. From 1828, when he took the United States by storm, to 1860, when he and South Carolina dissolved the Union, Rhett saw clearly that the North and the South were separate peoples, with starkly differing political beliefs, economic interests, and cultural values. At first, Rhett saw States’ rights as the only safeguard of the South’s liberty and security in the Union, but as the conflict between the North and the South deepened, he saw States’ rights as the South’s only way out of the Union. Rhett stood at the culmination of the sectional conflict and in the shadow of a distinguished Southern political tradition: the Founders Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who first enunciated States’ rights in the Virginia & Kentucky Resolutions; the jurists St. George Tucker and Abel P. Upshur, who systematized States’ rights in their scholarly works; the philosopher John Taylor of Caroline, who ruminated on States’ rights in his treatises; and the statesman John C. Calhoun, who honed States’ rights during the Tariff Crisis and many other political battles. Rhett turned States’ rights from a constitutional theory into a battle cry, putting into action what his predecessors had put down into words. Thus, when Confederates like McCrady took up arms, they were not fighting for slavery, but for States’ rights – the same cause of independence and self-government which had fired the hearts and minds of their Revolutionary forefathers. McCrady closed his speech with a poem which beautifully captured their defeated but not dishonoured cause:

Believing

That they fought, for Principle against Power,

For Religion against Fanaticism,

For Man’s Right against Man’s Might,

These Men were Martyrs of their Creed;

And their Justification

Is in the holy keeping of the God of History.But, for as much

As alike in the heat of Battle,

In the weariness of the Hospital,

And in the gloom of hostile Prisons,

They were faithful unto death,

Theirs is the Crown

Of a loving, a glorious, and an immortal Tradition,

In the Hearts, and in the Holiest Memories

Of the Daughters of their People;

Of the Sons of their State;

Of the Heirs Unborn of their Example

And all of for whom

They dared to die.

Excellence! Thanks for educating me on Robert B. Rhett.