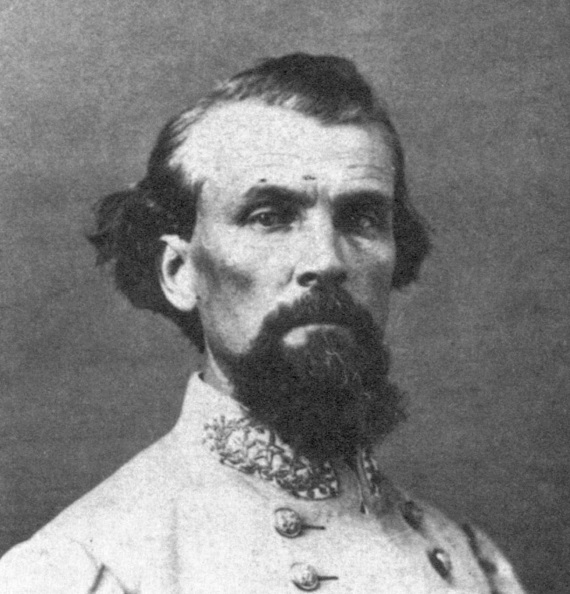

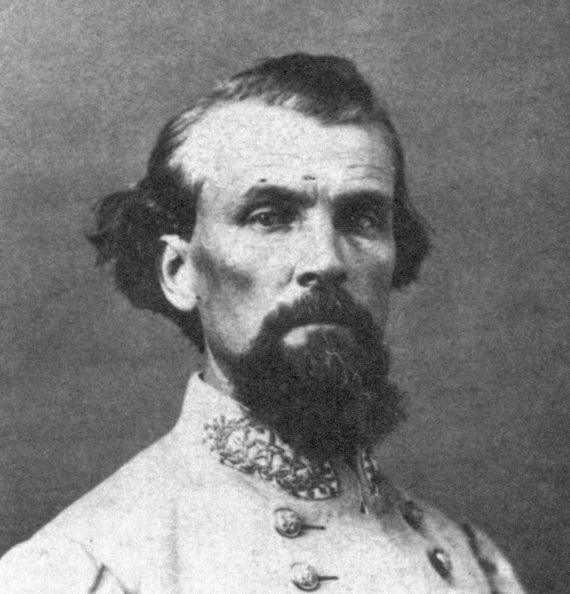

Foreword for A Rebel Born: A Defense of Nathan Bedford Forrest, Confederate General, American Legend, by Lochlainn Seabrook, Sea Raven Press, 2010.

There is a story that a year or two after the great American war of 1861–1865, a visiting Englishman asked Gen. R.E. Lee, “Who is the greatest soldier produced by the war?” It is reported that Lee without hesitation replied: “A gentleman in Tennessee whom I have never met. His name is Forrest.”

There can be no doubt that Bedford Forrest was one of the great captains of history.

Time and time again he defeated much larger forces in battle. Other enemy forces he regularly dispersed, captured, and deprived of their supplies. By bold and quick movement, accompanied by a genius for terrain and for surprising his opponents, he tied down or diverted large opposing armies. Time and again he raised new forces and equipped them from the enemy.

General J.E.B. Stuart is justly celebrated for his ride around the Union army in Virginia in 1862. More than once Forrest rode around Union armies into occupied Kentucky and Tennessee, eluding or thwarting every cavalry expedition sent against him and returning home with vast booty of horses, provisions and equipment, prisoners, and recruits. Beyond his accomplishments as a soldier, Forrest was and remains a hero to the people of the mid-South that he led in resistance to a vicious invasion.

Forrest’s record is even more impressive when we remember that the armies he opposed were the biggest ever mustered in the century between Napoleon and World War I. It is no wonder that General William T. Sherman called Forrest “that devil” and said that no resources should be spared to find Forrest and murder him. It is a plain fact, whatever efforts are made to deceive us, that the labels “war criminal” and “terrorist” fit General Sherman well, but do not fit General Forrest at all. Even so, when he was finished shooting and burning, Sherman said that Forrest was “the most remarkable man the Civil War produced on either side.”

There was a long period in the earlier twentieth century when the Confederacy and its heroes were considered an honoured part of American history, when the War was viewed as a great national tragedy with good and bad on both sides. That was the spirit of the centennial in the 1960s. As we enter the sesquicentennial observance, it is clear that the times are changed mightily, and that interpretation of history is to be dominated by people who will use every sort of falsehood, distortion, and emotional fury they can perpetrate to banish the Confederacy into one dark little corner labeled “slavery and treason.”

It is clear also that this hate campaign is directed not just at the Confederacy but at the entire South and its people, past, present, and future. It is equally evident that the campaign I am referring to does not rest upon any special knowledge or understanding of history or any concern about the truth of history. The first axiom of a real historian is that history—the acts of our predecessors of the human race and the times in which they acted— are complicated and should be approached with open mind and with the intent to understand rather than to hasten to condemnation. For instance, the present authorities do not know that hundreds of black Americans paid their respects to General Forrest at his funeral, while black people were not allowed at Lincoln’s funeral. (Indeed, most of them had been banished from Springfield by mobs before the war of “emancipation,” at the time Lincoln was a prominent citizen of the city.) If the present authorities were confronted with these facts, they would scream loudly that it’s not true and make sure that as few people as possible heard about it. A few of the more honest might make up elaborate excuses why the facts don’t really mean what they say. But any true history is a living thing, always open to debate, new evidence, and different perspectives.

Instead of wholesaling a phony image of Forrest as a unique monster, a writer who really understands American history would note his strong resemblance to Andrew Jackson. Though of different generations, both were Tennesseans, raised on the Southern frontier. Both survived difficult early years to emerge as men of indomitable courage, inspired leadership, fierce personal pride, and decisive action and few words. Both were self-made men without much formal schooling. Neither was a professional military man, but both learned to lead Southerners volunteers to victory over the forces of imperial governments. Only their times were different. Jackson came along when a Southern spirit was large in the guidance of the United States, Forrest when new forces were seeking domination and suppressing the old. That is history as life rather than mere material for propaganda labels.

The hatred of the South does not rest upon historical judgment. It is the result of an ideological will to power in which propaganda slogans are repeated again and again to stop independent thought and discussion and impose an official party line of historical interpretation. V.I. Lenin wrote this play book for his disciples. One also wonders about the quality of the American patriotism shown by the haters of Forrest. Could it match that of Forrest’s grandson, General Nathan Bedford Forrest, U.S. Army, who died in 1943 when his flying fortress was shot down during a raid over Germany?

One recent would-be historian of the War, who regards everything positive that can be said about the Confederacy as a “Lost Cause Myth,” wonders in print how anyone today can admire such an awful character as Forrest. The proper question to ask is, rather, how can any normal human being not admire a hero who defended his people with tremendous courage and skill against a superior enemy intent on conquest? Horatio at the Bridge, Roland at Ronscevalles, the defenders of the Alamo, Forrest belongs in that great pantheon of heroes.

He is also a great American, and American history cannot be understood without Forrest in his proper place. That is why Mr. Seabrook’s accounting of the truth of Forrest and his enemies that is presented here is so welcome and has appeared with such perfect timing.