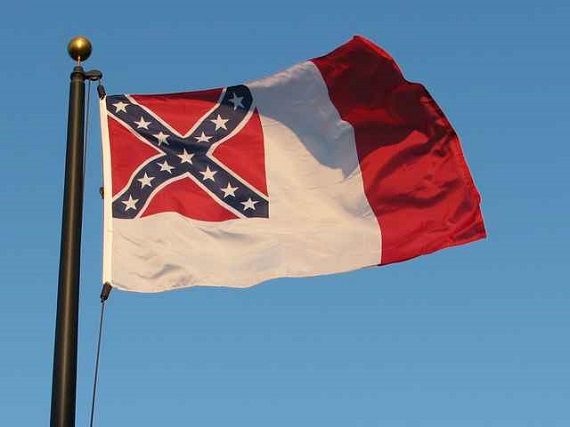

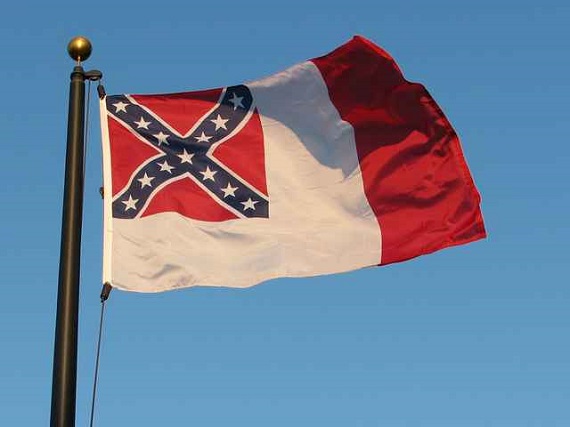

Back in mid-June, after the Charleston shootings, the frenzied hue and cry went up and any number of accusations and charges were made against historic Confederate symbols, in particular, the Confederate Battle Flag (which is not as some supposedly informed writers called it, “the Stars and Bars.” The Stars and Bars is a different flag with a totally different design). The best way to examine these charges in a short column is point by point, briefly and succinctly.

First, the demand was made that the Battle Flag needs to come down, that images of that flag need to be banned and suppressed, because, whatever its past may have been, it has now become in the current context a “symbol of hate” and “carried by racists,” that it “symbolizes racism.” The problem with this argument is both historical and etiological.

Historically, the Battle Flag, with its familiar Cross of St. Andrew, was a square ensign that was carried by Southern troops during the War Between the States. It was not the national flag of the Confederacy that flew over slavery, but, rather, was carried by soldiers, 90-plus per cent who did not own slaves (roughly comparable to percentages in certain regiments of the Union army with some slave holding soldiers from Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri in its ranks; indeed, General Grant’s wife, Julia Dent Grant, owned slaves).

By contrast, the American flag, the “Stars and Stripes,” not only flew over slavery for seventy-eight years, it flew over the brutal importation, the selling and the purchase of slaves, and the breaking up of slave families. Additionally, the Stars and Stripes flew over the infamous “Trail of Tears,” at the Sand Creek massacre of innocent Native Americans, later at the Wounded Knee massacre, over the harsh internment of thousands of Nisei Japanese American citizens in concentration camps during World War II, and during the action at My Lai during the Vietnam War.

Although there are some zealots who now suggest doing away with the American flag because of these connections, I would suggest that most of the pundits on the Neoconservative Fox News and amongst the Republican governors presently clamoring for banning the Battle Flag would not join them in that demand. Yet, if we examine closely the history of both banners from the radically changing contexts that are used to attack the one, should we not focus on the history of other, as well? And, if only a particular snap shot context is used to judge such symbols, is any symbol of America’s variegated history safe from the hands of those who may dislike or despise this or that symbol?

Second, a comparison has been made between the Battle Flag and the Nazi flag (red background, with a white circle and a black swastika centered). Again, this comparison demonstrates a lack of historical acumen on the part of those making it: the Nazi flag was created precisely to represent the Nazi Party and its ideology. The Battle Flag was designed to represent the historic Celtic and Christian origin of many Southerners and served as a soldiers’ flag.

Third, the charge has been made that we should ban Confederate symbols because they represent “treason against the Federal government.” That is, those Southerners who took up arms in 1861 to defend their states, their homes, and their families, were engaged in “rebellion” and were “traitors” under Federal law.

Again, such arguments fail on all counts. Some writers have suggested that Robert E. Lee, in particular, was a “traitor” because he violated his solemn military oath to uphold and defend the Constitution by taking arms against the Union. But what those writers fail to note is that Lee had formally resigned from the US Army and his commission before undertaking his new assignment to defend his home state of Virginia, which by then had seceded and re-vindicated its original independence.

And that brings us to point four: the right of secession and whether the actions of the Southern states, December 1860-May 1861, could be justified under the US Constitution.

One of the best summaries of the prevalent Constitutional theory at that time has been made by black scholar, professor, and prolific author Dr. Walter Williams. I quote from one his recent columns:

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, a proposal was made that would allow the federal government to suppress a seceding state. James Madison rejected it, saying, ‘A union of the states containing such an ingredient seemed to provide for its own destruction. The use of force against a state would look more like a declaration of war than an infliction of punishment and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might be bound.’

In fact, the ratification documents of Virginia, New York and Rhode Island explicitly said they held the right to resume powers delegated should the federal government become abusive of those powers. The Constitution never would have been ratified if states thought they could not regain their sovereignty — in a word, secede.

On March 2, 1861, after seven states seceded and two days before Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, Sen. James R. Doolittle of Wisconsin proposed a constitutional amendment that read, “No state or any part thereof, heretofore admitted or hereafter admitted into the union, shall have the power to withdraw from the jurisdiction of the United States.”

Several months earlier, Reps. Daniel E. Sickles of New York, Thomas B. Florence of Pennsylvania and Otis S. Ferry of Connecticut proposed a constitutional amendment to prohibit secession. Here’s a question for the reader: Would there have been any point to offering these amendments if secession were already unconstitutional? [my emphasis added]

Let me add that an examination of the ratification processes for Georgia, South Carolina, and in my own North Carolina in the late 1780s, reveal very similar discussions: it was the independent states themselves that had created a Federal government (and not the reverse, as Abe Lincoln erroneously suggested), and it was the various states that granted the Federal government certain very limited and specifically enumerated powers, reserving the vast remainder for themselves. As any number of the Founders indicated, there simply would not have been any United States if the states, both north and south, had believed that they could not leave it for just cause.

Interestingly, in my many years of research I can find only a couple of American presidents who openly and frankly denied the right of secession or believed in the Constitutional right to suppress it (of course, there is John Quincy Adams). In his address to Congress in January of 1861, lame duck President James Buchanan, while deploring secession in the strongest terms, stated frankly that he had no right to prevent it: “I certainly had no right to make aggressive war upon any State, and I am perfectly satisfied that the Constitution has wisely withheld that power even from Congress.” Former President John Tyler served in the Confederate Congress, and former President Franklin Pierce, in his famous Concord, New Hampshire, address, July 4, 1863, joined Buchanan in decrying the efforts to suppress the secession of the Southern states:

Do we not all know that the cause of our casualties is the vicious intermeddling of too many of the citizens of the Northern States with the constitutional rights of the Southern States, cooperating with the discontents of the people of those states? Do we not know that the disregard of the Constitution, and of the security that it affords to the rights of States and of individuals, has been the cause of the calamity which our country is called to undergo?

More, during the antebellum period William Rawle’s pro-secession text on Constitutional law, A View of the Constitution of the United States (1825,) was used at West Point as the standard text on the US Constitution. And on several occasions the Supreme Court, itself, affirmed this view. In The Bank of Augusta v. Earl (1839), the Court wrote in an 8-1 decision:

The States…are distinct separate sovereignties, except so far as they have parted with some of the attributes of sovereignty by the Constitution. They continue to be nations, with all their rights, and under all their national obligations, and with all the rights of nations in every particular; except in the surrender by each to the common purposes and object of the Union, under the Constitution. The rights of each State, when not so yielded up, remain absolute.

A review of the Northern press at the time of the Secession conventions finds, perhaps surprisingly to those who wish to read back into the past their own statist ideas, a similar view: few newspapers took the position that the Federal government had the constitutional right to invade and suppress states that had decided to secede. Indeed, were it not the New England states in 1814-1815 who made the first serious effort at secession during the War of 1812, to the point that they gathered in Hartford to discuss actively pursuing it? And during the pre-war period various states asserted in one form or another similar rights.

One last point regarding the accusation of “treason”: after the conclusion of the War, the Southern states were put under military authority, their civil governments dissolved, and each state had to be re-admitted to the Union. Now, unless my logic is wrong, you cannot be “re-admitted” to something unless you have been out of it. And if you were out of it, legally and constitutionally, as the Southern states maintained (and many Northern writers acknowledged), then you cannot be in any way guilty of “treason.”

The major point that opponents of Confederate symbols assert currently is that the panoply of those monuments, flags, plaques, and other reminders actually represent a defense of slavery. And since we as a society have supposedly advanced progressively in our understanding, it is both inappropriate and hurtful to continue to display them.

Again, there are various levels of response. Historically, despite the best efforts of the ideologically-driven Marxist historical school (e.g., Eric Foner) to make slavery the only issue underlying the War Between the States, there is considerable evidence–while not ignoring the significance of slavery–to indicate more profound economic and political reasons why that war occurred (cf. writers Thomas DiLorenzo, Charles Adams, David Gordon, Jeffrey Hummel, William Marvel, Thomas Fleming, et al). Indeed, it goes without saying that when hostilities began, anti-slavery was not a major reason at all in the North for prosecuting the war; indeed, it never was a major reason. Lincoln made this explicit to editor Horace Greeley of The New York Tribune a short time prior to the Emancipation Proclamation (which only applied to states in the South where the Federal government had no authority, but not to the states such as Maryland and Kentucky, where slavery existed, but were safely under Union control).

Here is what he wrote to Greeley on August 22, 1862:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy Slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about Slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union, and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a desperate political ploy by Lincoln to churn up sagging support for a war that appeared stale-mated at the time. Indeed, Old Abe had previously called for sending blacks back to Africa and the enforcement of laws that made Jim Crow look benign. He knew fully well that “freeing the slaves” had no support in the North and was not the reason for the conflict.

Professor DiLorenzo, returning afresh to original sources, focuses on the deeper, all-encompassing economic motives:

Whatever other reasons some of the Southern states might have given for secession are irrelevant to the question of why there was a war. Secession does not necessitate war. Lincoln promised war over tax collection in his first inaugural address. When the Southern states refused to pay his beloved Morrill Tariff at the Southern ports [monies that supplied a major portion of Federal revenues], he kept his promise of ‘invasion and bloodshed’ and waged war on the Southern states.

Indeed, late in the conflict the Confederate government authorized the formation of black units to fight for the Confederacy, with manumission to accompany such service. According to Ervin l. Jordan, Jr. (Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia, University of Virginia, 1995), thousands of black men fought for the Confederacy, perhaps as many as 30,000. Would a society ideologically intent on preserving in toto the peculiar institution as the reason for war, even in such dire straits, have enacted such a measure?

It is, of course, easy to read back into a complex context then what appears so right and natural to us now; but it does a disservice to history, as the late Professor Eugene Genovese, perhaps the finest historian of the Old South, fully understood. Understanding the intellectual struggle in which many Southerners engaged over the issue of slavery, he cautioned readers about rash judgments based on politically correct presentist ideas of justice and right, and in several books and numerous essays defended those leaders of the Old South who were faced with difficult decisions and a nearly intractable context. And more, he understood as too many writers fail to do today, that selecting this or that symbol of our collective history, singling it out for our smug disapprobation and condemnation, may make us feel good temporarily, but does nothing to address the deeper problems afflicting our benighted society.

Concerning Dylann Roof, the disturbed lone gunman responsible for the Charleston shootings, our proper response should be: if a rabid fox comes out of the woods and bites someone, you don’t burn the woods down, you stop the fox.

But in the United States today we live in a country characterized by what historian Thomas Fleming has written afflicted this nation in 1860–“a disease in the public mind,” that is, a collective madness, lacking in both reflection and prudential understanding of our history. Too many authors advance willy-nilly down the slippery slope–thus, if we ban the Battle Flag, why not destroy all those monuments to Lee and Jackson. And why stop there? Washington and Jefferson were slave holders, were they not? Obliterate and erase those names from our lexicon, tear down their monuments! Fort Hood, Fort Bragg, Fort Gordon? Change those names, for they remind us of Confederate generals! Nathan Bedford Forest is buried in Memphis? Let’s dig up him up! Amazon sells “Gone with Wind?” Well, to quote a writer at the supposedly “conservative,” Rupert Murdoch-owned New York Post, ban it, too!

It is a slippery slope, but an incline that in fact represents a not-so-hidden agenda, a cultural Marxism, that seeks to take advantage of the genuine horror at what happened in Charleston to advance its own designs which are nothing less than the remaking completely of what remains of the American nation. And, since it is the South that has been most resistant to such impositions and radicalization, it is the South, the historic South, which enters the cross hairs as the most tempting target. And it is the Battle Flag–true, it has been misused on occasion–which is not just the symbol of Southern pride, but becomes the target of a broad, vicious, and zealous attack on Western Christian tradition, itself. Those attacks, then, are only the opening salvo in this renewed cleansing effort, and those who collaborate with them, good intentions or not, collaborate with the destruction of our historic civilization. For that they deserve our scorn and our most vigorous and steadfast opposition.

I found the proposed constitutional amendment by Doolittle of Wisconsin.

I can not find the amendment by Sickles, Ferry & Florence. Have you ever seen it?

Thanks.