In the 1850s, Ann Pamela Cunningham, a frail woman from South Carolina, was responsible for preserving the plantation home of George Washington, founding the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, an organization which still maintains this historic site. Thanks to her efforts, Mount Vernon remained virtually untouched during the War for Southern Independence. Arlington Plantation, the beautiful Virginia home of Robert E. Lee, however, was not so fortunate.

John Augustine Washington, Jr., the great grand-nephew of George Washington, had inherited Mount Vernon but was without the means to keep up the property. The buildings were becoming dilapidated, and the portico of General Washington’s mansion was propped up by pine boards to keep it from collapse. Not receiving enough income from the property, but wishing it to be preserved because of its historical significance, John A. Washington offered it to the U.S. Congress, hoping that the government would wish to restore and maintain the site of its first president’s home and tomb. He was asking for $200,000.00 dollars, but the government declined to purchase. He then offered it to the state of Virginia, and its government also declined.

Patricia West’s book, Domesticating History, which deals in part with Miss Cunningham and the war, states: “Cunningham, though a moderate, was sympathetic to her native South … Tensions were high when Cunningham made her way home … early in 1861, stopping in Charleston where the ill-fated Fort Sumter stood in the harbor. ‘Excited and indignant feelings’ overcame her as she condemned the North’s Maj. Robert Anderson for actions taken to hold the contested fort, which she argued would ‘make a war inevitable.’”

Miss Cunningham “emphasized that only by adherence to the ‘principles’ of Washington, which would preclude Northern ‘factional injustice,’ could the Union be preserved … Secession, she argued, was legal, and the North’s ‘aggressiveness’ and ‘violations of the Constitution’ were to blame for the war. She said, ‘While I never wished for secession, when it came I joined fate with the South as was but right.’”

West’s book also relates that during the war, Miss Cunningham invested some of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association funds in Confederate bonds. Another piece of evidence of her support for the southern war effort can be found in the book South Carolina Women in the Confederacy, which records that in November 1864, Miss Cunningham contributed items to be sold in a fund raising bazaar for the benefit of the Soldiers’ Relief Association in South Carolina. In a list of donations it records the following: “Several fancy articles, among them a fine head of Washington in a frame made from wood taken from Mt. Vernon, from Miss Pamela Cunningham. “

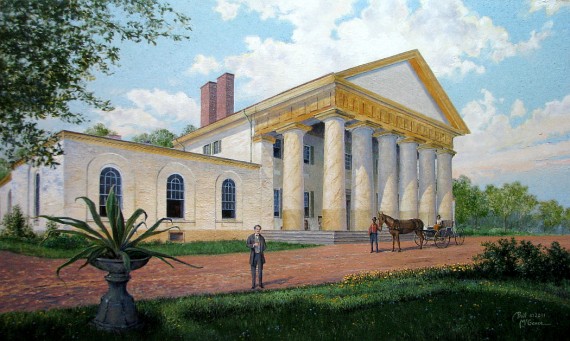

The last private owner of Mount Vernon, John Augustine Washington, vacated the mansion with his family for a new plantation home in February 1860. The following year, Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops made it clear that the United States would go to war against the seceded Southern states, and though Virginia had originally voted to remain in the Union, her convention delegates now voted in favor of secession. Along with several other Washington family members, John A. Washington joined the Confederate Army to fight for the South. With the rank of lieutenant colonel, he served as an aide-de-camp to his cousin General Robert E. Lee. In September 1861, Colonel Washington was killed at the Battle of Cheat Mountain.

One of the many American women who responded to the call for the preservation of Mount Vernon was Loula Kendall Rogers. As a girl, Rogers became the “Lady Manager” of the Mount Vernon Association in her county in Georgia. She later recalled in her reminiscences:

[I] felt no little pride in the thought of what a young girl could do toward preserving the home of Washington as a precious heirloom of our very own, never to be desecrated for other purposes but to be kept sacred to the memory of the “Father of our Country.” No section contributed more than the Southern States, and as he was a true-hearted son of the South, we we still value above gold our interest in his lovely home, and its twin sister “Arlington, the Beautiful,” which should have been held sacred in like manner, as the home of General Robert E. Lee and his bride.

Unlike Mount Vernon, Arlington, the home of Robert E. Lee and his wife Mary Custis Lee, a great grand-daughter of Martha Washington, was not held sacred. Arlington was initially seized by Federal forces early in the war, and as soon as they had possession of it, they began looting the house. It was filled with many items which had belonged to George and Martha Washington, including portraits, china, Washington’s bed, and other things from Mount Vernon. Those relics not carried away or destroyed by soldiers were taken to Washington, D.C. and placed in the Patent Office, where they were exhibited with the label “Captured from Arlington.”

Mrs. Lee’s housekeeper, a slave woman named Selina Gray, confronted the soldiers and managed to save many of these priceless heirlooms, although many other items, including things from Mount Vernon, were stolen from the house or ruined by soldiers. Like all the slaves whom Robert E. Lee inherited from his father-in-law, Gray was freed in 1862.

In the early days of the conflict, Arlington was first seized by Federal troops to prevent its use as an artillery emplacement by the Confederates. This could be understood as a matter of military necessity. What happened at Arlington later on, however, was not a matter of military necessity, but hatred and revenge. A military cemetery was created there in 1864, when soldiers were buried next to the house. Their graves, Mrs. Lee wrote, were “planted up to the door without any regard to common decency.” By the end of the war, thousands of soldiers were buried around her former home.