Many people are familiar with the Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers Project of the 1930s. While some historians reject them for what has been called gross inaccuracies due in large part to the many positive memories of the institution (the negative accounts are always used), they have become the standard source for firsthand information on the institution from the people themselves. These accounts are part of the fabric of the Southern history and serve as a window in the lives of antebellum black Americans.

But most people, historians included, fail to consider the importance of antebellum and post-bellum literature in the assessment of black American culture. William Faulkner received great acclaim for his use of dialect in tales about life in Mississippi, but because his stories are fiction, they fail to attract the historical profession as a useful tool in understanding Southern culture, race relations, or Southern life, particularly those that display a complexity, more accurately a positivity, about Southern relationships and the Southern tradition.

Faulkner is the most conspicuous Southern author in his use of dialect, but he was not alone. Antebellum Southern literature is saturated with the true language of both white and black Southerners. Most of it will never be read in American classrooms. After the war, men like Joel Chandler Harris of Uncle Remus fame and Thomas Nelson Page were pioneers in the use of dialect, which in turn brought a more complex South into focus. Even into the mid-twentieth century, most Americans had read the tales of Uncle Remus and perhaps had at least a cursory understanding of In Ole Virginia.

Dialect writing, particularly in black folk tales, is a useful tool in understanding the Southern black community. One writer virtually unknown today but who spent years collecting and publishing black folk tales was Anne Virginia Culbertson. Born in Ohio in 1864, Culbertson traveled around Virginia and North Carolina in the post war years interviewing black Southerners and then re-telling their folk tales. She even learned to perform some of the folk tunes and was in high demand for her work. Most of the stories were decades old and could be traced to the traditions of Southern slaves.

These folk tales are rarely critical of Southern life and instead display a longing for home and hearth similar to that which the Federal Writers Project authors found among former slaves in the 1930s. There is continuity in the story. Race relations were often amicable and informal, and black Southerners loved the South as much as their white neighbors. They could claim a nearly three-hundred year attachment to the land.

One of Culbertson’s works, Banjo Talks, is a collection of folk songs Southern blacks sang both before and after the War. None are dreary recollections of Southern life, of the poverty or hardship that the modern reader would expect to find, particularly if current portrayals of all things Southern are to be believed.

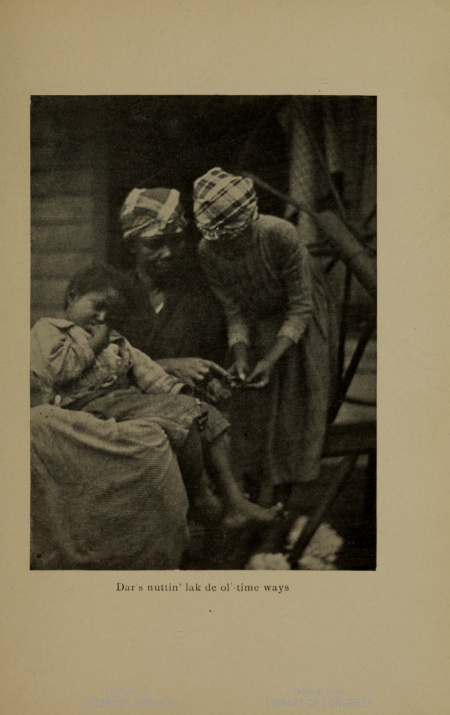

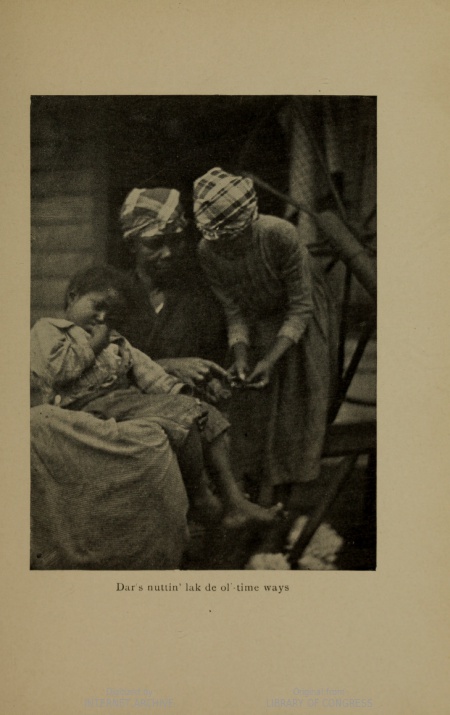

One song, titled “With the Spinning Lesson,” begins “Dar’s nuttin’ lak de ol’-time ways, I tell you dem ol’ days wuz days!” and shows pride in their work, “’Kase all we had ter eat an’ wear Wuz made right yer on dis plantation, Hit sut’n’y jes’ beat all creation! We spinned an’ dyed an’ weabed an’ knit. An’ tu’ned out gyarmints dat wuz fit Per any pusson in dis nation.”

Another, titled “Knockin’ De ‘Rang-A-Tang” is a song dedicated to a Christmas gathering. “Dough de cabin mighty small, Room fer ev’y comer Dar we darnses one an’ all, Lawdy! beats de summer! Lightwood fire blazin’ bright Meks de place all warm an’ light, Darkies darnse wid all dey might, A happy, singin’, laffin’ gang, Hit’s den we knocks de ‘rang-a-tang. We knocks de ‘rang-a-tang.”

Virtually every story written in the antebellum South, even those by abolitionists like 12 Years A Slave, told of the special place Christmas had amongst the black Southern community.

Certainly, in many folk songs and slave narratives the prospect of freedom is a welcomed event. A song tilted “’Pen’ence” in Banjo Talks expresses joy at the coming of emancipation. The narrator is so overcome with emotion that she declares at the birth of her baby, “”Bress Gawd, dis ain’ a slave dat’s bawn ter me! I’se gwineter call dis chile, you year me say, ‘Mancipation Proclaniation Innepen’ence Day!”

But even with emancipation came a certain social strain, as the generation born after slavery did not seem to respect life and community as much as their elders. In “Jes Lookin’ On” an eighty year old former slave shows disgust with the manners of the young folk of his community. “Some er dis wufless young cullud trash Dey calls me ”Uncle” an ac’s real brash, Jes’ laffin’ behime my back lak sin, ‘Kase I bin a slave an’ dey ain’ bin. I ru’rr bin bonded my natchel days Dan ter ac’ in sech no-kyount, trashy ways. I reckon hit’s well we wuz all set free, I s’pose dat’s de way folks wuz meant ter be.”

Other themes in the book include love, farming, Christianity, and a virtually careless appreciation for life and nature. There was no hint of social angst or physical degradation. Black Southerners, like many of their white counterparts, lived on the land in what we would consider poverty today, but at least according to their folk songs, there was a calm and fluid oneness with the world.

It is easy to accept harsh descriptions of slavery and black Southern life in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They happened. But it is far less agreeable—maybe even palatable for some—to also accept the positive descriptions of black Southern life that came from black Southerners themselves. This is problematic. If we wish to live in a respectful society between black and white Southerners (which, frankly, already exists on a daily basis), then we should be honest with Southern history and show the South and the Southern people in all their complexities. Hasn’t that been the stated goal after all? Judging by our simplistic pop culture and “education” system, probably not.