Sometime around 1939, Lead Belly sang the song Daddy I’m Coming Back to You, which features the interesting lyrics: “I’m dreaming tonight of an old Southern town, the best friend I ever had…I’ve had my way, but now I’ll stay, I long for you and for home.”

The song was a tribute to Jimmie Rodgers, who is often considered one of the fathers of country music. The fact is that Lead Belly, like many African Americans in his day, had a complicated history with race, but he always loved the South and southern music. Lead Belly should be remembered as a treasure that sang gospel, blues, country, and “folk” ballads. He was also multi-talented musician that played harmonica, accordion, piano, violin, mandolin, and was even labeled “king of the twelve string guitar.”

Lead Belly was born Huddie (pronounced Hugh-dee) Ledbetter in 1881 on the Jeter Plantation near Mooringsport, Louisiana. His family lived on the frontier, owned their own land, and encouraged his musical talents early on. As a young boy, Lead Belly learned mandolin and accordion while sitting in rocking chairs not far from the swamps. His mother led the church choir and he had two uncles that knew how to play a wide variety of songs. He sometimes played organ for local church services, and got his start as a songster playing at rough-and-tumble bars near Shreveport.

By age sixteen, Lead Belly was married with two kids and by his twenties, he was divorced and rambling the streets of Texas to play music with Blind Lemon Jefferson. He was reputed to have as many as 500 songs stored away in his mind. For many years, Ledbetter farmed in the summer and played music in the winter. He enjoyed performing, but being a musician in these dangerous neighborhoods often led to many alcohol-fueled, violent encounters. His budding career as a musician came to a halt at the age of 27 when he got into a barroom brawl and punched a man in the face, then pulled a pistol and pummeled another man with it. He was sentenced to hard labor on a chain gang in Texas, escaped after just two days, and then went right back to working as a hopeful musician.

Having assumed the alias Walter Boyd, Lead Belly kept a low profile for some time but his short temper eventually got him into trouble again. In 1917 at the age of 33, his cousin was having some issues with her husband and Lead Belly showed up to her house with a pistol and knife. In the ensuing argument, he shot the husband dead and then proceeded to knock another man out. Lead Belly maintained the other man drew his pistol first, and that he was only acting in self defense, but he was hastily convicted and sentenced to 7-35 years. His family even lost their farm because of the costs to secure a lawyer for his defense.

While imprisoned in Texas, he tried to escape during his first year and got transferred, then decided to try and focus all his efforts on music and securing an early release. One day, Texas Governor Pat Neff visited the prison and Lead Belly sang him a song. Neff apparently returned several times with guests to watch him perform and commuted his sentence in 1925. One of the country’s leading black newspapers, The Philadelphia Independent wrote an article titled “Two-Time Dixie Murderer Sings Way to Freedom” and had the following to say about the pardon:

Asked what inspired him to sing to attract the attention of Governor Pat Neff, Lead Belly said he thought of the Biblical Paul and Silas in prison. He reviewed how they both sang and prayed at the midnight hour…and how the earth trembled and the walls of the prison shook, the locks on the cell doors fell and they walked out free. Lead Belly visioned the Biblical miracle and it seemed as if the very locks on the prison cell were dropping. But they weren’t. Then he sang a song he had composed himself. He waited until Governor Neff made his regular visit to the prison and then serenaded the Texas chief executive with the lines, “If I had you, Hon. Governor Neff, where you got me, I’d wake up in the morning and set you free.”

Five years later, Lead Belly was jailed again in Louisiana. His family explained that while he was listening to a group of Salvation Army musicians in Shreveport, he began to do a soft-shoe dance, but was rushed by a group of white men looking for a fight. Lead Belly drew the penknife he used for slides on his guitar, cut a man, and ended up receiving a five to ten year sentence at Angola.

During this prison stint, a man came from behind and stabbed Lead Belly in the neck with a prison shank. Lead then threw the man onto the ground, pulled the shank from his own neck, and almost killed the man with it. It was around this time Leadbetter acquired the nickname “Lead Belly,” either because of his incredible strength and toughness, his high tolerance for bathtub moonshine, or because he had allegedly taken a gunshot to the abdomen. While the exact source of the nickname is debatable, it has a fitting forcefulness.

In 1933, a historian and folklorist named John Lomax first heard Lead Belly sing and play guitar at Angola. Lomax then sent some recordings to Louisiana governor Oscar K. Allen, and Lead Belly was released in 1934 (some sources say that Depression conditions and good behavior were the main reasons for his release). Lomax and Lead Belly then traveled the south together, arranged a partnership, and eventually traveled to New York to promote Lead Belly’s talent.

Along the way, Lead Belly performed for the Modern Language Association, Ivy League colleges, and the Library of Congress. His time served in prison made him appealing to many audiences that branded him as more “authentic” than many other artists in his genre. But Lead Belly considered himself a legitimate black cowboy and wanted to crossover into country and western music. He felt like he had a lot more to offer than the blues, but that was what northern audiences expected of him.

The sad truth is that northern audiences preferred the newer, flashier music of men like Cab Calloway. An article in the New York Tribune on January 3, 1935 was stereotypically titled: “Lomax Arrives with Lead Belly, Negro Minstrel. Sweet Singer of Swamplands Here to Do a Few Tunes Between Homicides.” It went on to say that Lead Belly was a musician with “no idea of money, law or ethics, and who was possessed of virtually no self restraint.” The same Tribune author wrote another scathing headline a year later titled: “Ain’t it a Pity? But Lead Belly Jingles Into City Ebony Shufflin’ Anthology of Swampland Folksong Inhales Gin, Exhales Rhyme.”

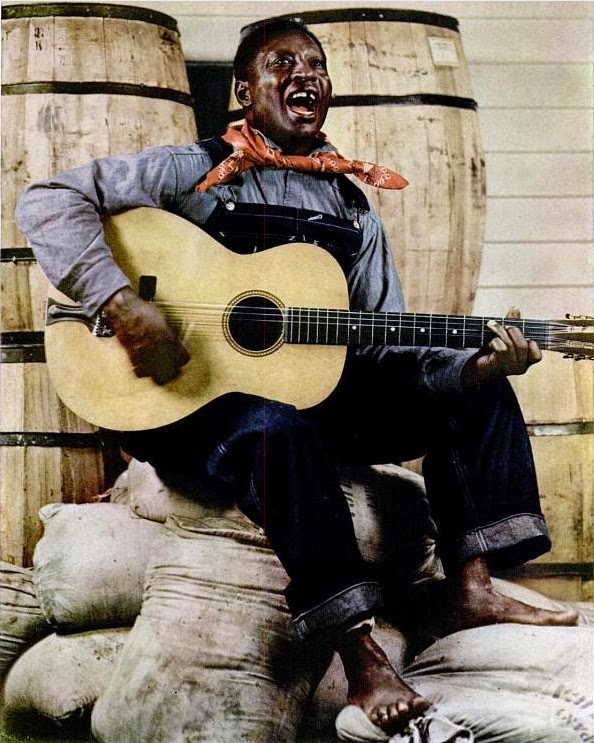

On Easter Week in 1936, Lead Belly performed at the Apollo theatre and a vocal audience was unkind to him. The New York Age, a black paper, even left him an unfavorable review. New York’s Life magazine had a review of Lead Belly in April 1937 titled “Bad N***** Makes Good Minstrel” and featured a large photo of Lead Belly barefoot, in overalls, sitting a top bags of grain and singing (a throwback to the minstrel shows of old).

The 1937 LIFE Magazine image of Lead Belly. You won’t see images of Lead Belly dressed like this in the south:

The nightlife in New York was attractive to Lead Belly and it would not be long before he was back to his drinking, rambling ways–which caused his relationship with John Lomax to sour. On one occasion in 1939, he got into a knife fight with a man in Manhattan (the man may have made advances on his wife) and stabbed the man sixteen times! He was able to get time taken off of his sentence because, while out on bond, he prevented a liquor store robbery by tackling the robber and holding him down until police arrived. He went on to continue performing and was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease while on a European tour in 1949. His songs like “Goodnight Irene,” “Midnight Special,” “Pick a Bale of Cotton,” and “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” have inspired a wide variety artists like The Beatles, Johnny Cash, and Nirvana.

The politically correct, mainstream narrative of Lead Belly’s life is that he was a pardoned murderer who fled racism in the south, was exploited by his southern manager John Lomax, and was finally able to express himself as a “folk” artist in the north. The truth is that Lead Belly’s music was appreciated in the south, which is probably why he was released from prison there twice for violent crimes. He appreciated all the music of his southern homeland, but attitudes at the time portrayed him as a relic of the past. While he achieved some mixed success in the north, eventually partnering up with the likes of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, his musical variety was not as well received and he died before becoming a major commercial success. He also tried to partner up with John Lomax in his later years and received intermittent assistance from John’s son, Alan. But many histories will portray Lomax as an outright racist that humiliated and used Lead Belly for profit.

Lead Belly was a hard drinking, hard fighting, hell of a man that lived a legendary life. In a day where celebrities make headlines for Tweets, there’s something to be said about a man that literally forged his career with his fists. He is an artist that all southerners, black or white, can and should be proud of. Today, you can see a life size monument of Lead Belly at 416 Texas St, Shreveport, LA. His final place of rest is at Shiloh Baptist Church Cemetery at 10395 Blanchard-Latex Rd., Mooringsport, LA, 71060.