The chattering class’ newest obsession, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, has seized the policy initiative from the Democratic Party’s geriatrics by promoting a “Green New Deal.” T’is clever branding to combine left-wing eco virtue signaling with FDR’s version of “down home” fascism. (If one doubts me on this last point, I refer you to John Garraty’s seminal article, “The New Deal, National Socialism, and the Great Depression,” published in the American Historical Review back in 1973. Garraty, by the way, was a liberal admirer of FDR.) The basic idea is to make massive public investments in American infrastructure to shift the country from a polluting carbon-based system of energy and energy extraction to a sustainable utopia of sunshine and wind harvest. Ms. Ocasio-Cortez’s idea has gained traction among the hordes of folks seeking the Democratic Party’s nomination for the presidency of the United States. Critics threw a wet blanket upon all of this by asking the inconvenient question, “Who is going to pay for this?” The answer: Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Strip down the academic jargon and algebraic equations, and one finds that MMT operates on a few basic assumptions: 1. Government spending deficits result in an increase in private savings. 2. A government that only borrows money in its own currency cannot go bankrupt, because it can simply print more money to pay down its debt. 3. Inflation of prices is the only constraint on government spending. If inflation were to occur, taxes could be increased, and/or government spending cut to combat inflation. Voilà, the philosopher’s stone exists. Unfortunately, both the Green New Deal and modern monetary theory are fundamentally flawed, especially when the ideas behind these schemes make their way from the white board to the real world.

To best understand the Jeffersonian critique of modern monetary theory a short history of money is necessary. Pace dear central bankers and Mr. Buffet, but gold and silver are money. They are divisible, portable, exchangeable for goods and services, and a store of value. This last, a store of value, is what sets money apart from currency. Other commodities in certain cultures have served as money, but not with the longevity or universality of gold and silver. On rare occasions, silver has declined in value—the inflation in sixteenth century Europe was due to the flood of silver coming from Spanish holdings in the New World and increases in spending by the Spanish monarchy—but these instances have been rare and modest. In 1964, three silver dimes purchased a gallon of gas. Today, exchange those three silver dimes for Federal Reserve Notes and you get a gallon of gas plus change.

The world of money and banking in Jeffersonian days differed from our own in a few significant ways. First, gold and silver were recognized as money. Second, banks regularly issued notes through their lending activities, the notes being redeemable in silver and gold. These notes were the electronic currency and paper currency of the day. One could use these notes to purchase goods and services, but no merchant or other provider of goods and services was under an obligation to accept paper currency. What gave the paper money of Jefferson’s day value was the ability to exchange it for gold and silver. Woe to the bank that attempted to issue more notes via loans than they could comfortably redeem with silver or gold. Runs on the bank could and did result from such practices, thus notes redeemable in gold and silver acted as a constraint upon the ability of banks to inflate the currency.

The world of “money” we live in today is quite different. One bank, the Federal Reserve Bank (FRB), has a monopoly on the issuing of currency. This bank is a quasi-public, quasi-private bank. The chairman of the bank is appointed by the President of the United States, and Congress does exercise some oversight over the FRB via hearings. The FRB is subject to some political pressure, but the real pressure points are in the hands of its stockholders, which is a closely held secret, though these are most likely the large investment banks who are the main dealers in government debt: Citibank, JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs etc. The notes issued by the FRB are not redeemable in gold or silver; they are backed by the “full faith and credit of the United Sates” whatever that means in this day and age. Federal Reserve Notes are accepted by the federal and state governments in the payment of taxes, and they are legal tender. Nevertheless, whether one measures the value of the Federal Reserve Note by the amount of precious metals it can buy, or the good and services it can purchase, the Federal Reserve Note has lost over 90% of its value since its introduction in 1916. As a currency the notes are functional, but as a store of value they are pathetic.

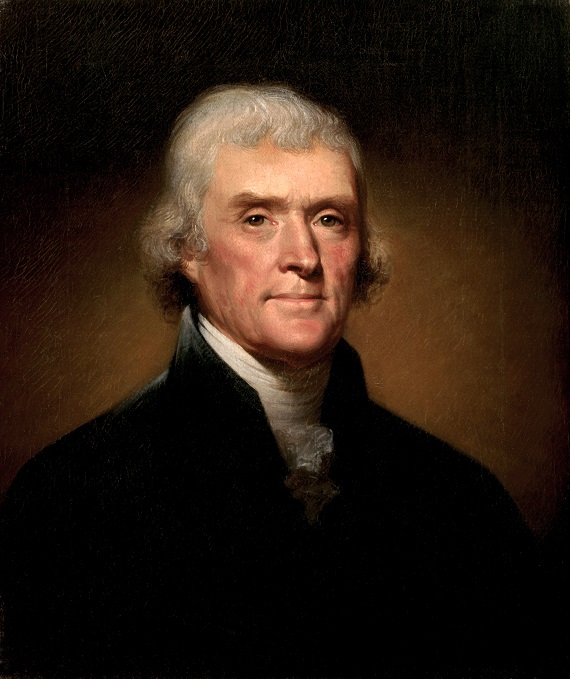

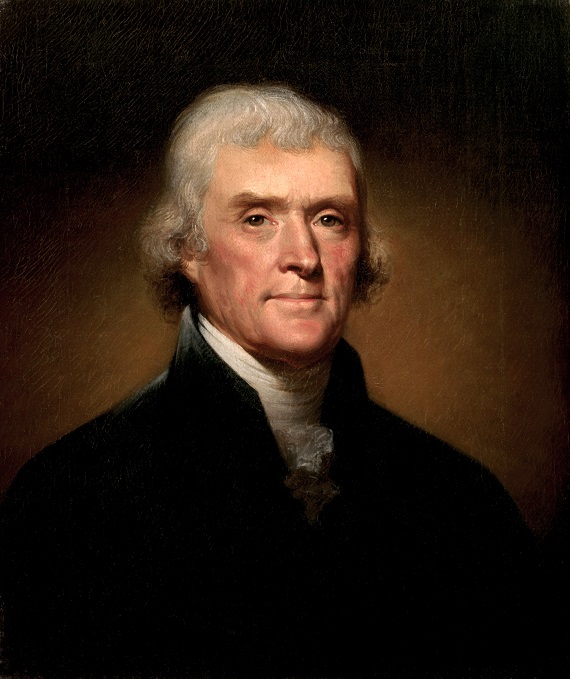

Thomas Jefferson, Albert Gallatin, John Taylor of Caroline, John Randolph of Roanoke, and John C. Calhoun were among the Jeffersonian republicans who closely studied money and banking, and most importantly, shaped monetary and banking policy in the early republic and antebellum period. The Jeffersonians were deeply concerned about the consolidation of both political and financial power, and they wished to prevent this consolidation. For this reason, Alexander Hamilton’s plan for a national bank was deeply concerned Jeffersonians. While Hamilton’s bank did not achieve a monopoly on the currency, it did create a situation where it could become the government’s chief creditor and thus exercise an undue influence upon national policy. Moreover, the Jeffersonians were concerned that Hamilton’s advocacy of a perpetual public debt would result in a system of perpetual taxation to pay the holders of the debt and the stockholders of the national bank. Hamilton conceded this point, but he found this an advantage, a way to bring men of capital into a symbiotic relationship with the new federal government.

Lastly, the Jeffersonians, especially John Taylor, realized that the expansion of currency via loans made to the federal government, could result in price inflation if the new currency was used by its recipients to purchase goods and services. Taylor recognized that price inflation was a tax that fell upon the farmers, artisans, and poorer classes. These folks did not have access to the new loans, more wealthy folks did. The wealthy recipients of this new money could then purchase goods and services before prices adjusted for the inflation in the currency. Essentially, the wealthy and powerful were able to use new currency to purchase goods and services at old prices. By the time the new currency made its way down the chain to farmers and artisans it was no longer “new,” and the prices of goods and services had adjusted upwards. The price increases of the goods and services purchased by the farmers and artisans almost always increased at a faster rate than the prices that these folks could command for their products and labor.

The Jeffersonian challenge was to propose an alternative to the Hamiltonian system. In the realm of practical public policy this took the form of a Treasury Department, independent of any central bank, issuing its own notes to meet the fiscal needs of the federal government. Proponents of the Hamiltonian system, to this day, criticized the Independent Treasury as a dangerous repetition of the old paper continental financial system used during the American Revolution, which resulted in a rapid debasing of the value of that paper currency.

There were, however, two significant differences between the old continentals and Treasury notes. First, Congress had no way of removing the continental from circulation because the Continental Congress lacked the power to tax. Second, the old continental, like today’s Federal Reserve Note, did not bear interest and it could not be exchanged for gold and silver as the Continental Congress had little to nothing in the way of silver or gold. The Jeffersonians pointed out that the Federal government did have a taxing authority to drain excess liquidity and fight price inflation, that Treasury notes could bear interests and thus retain their value, and that the government could certainly redeem any the Treasury notes in gold and silver. The Jeffersonians understood that confidence was the most important variable in a currency’s success. The risk premium, i.e. the interest rate attached to many of the Treasury notes used to finance the War of 1812, and the notes’ use for the payment of taxes went a long way to shoring up confidence in the Treasury note as a form of currency.

We know the Jeffersonians to be correct in this assessment. During the War of 1812, the federal government used a mixed system of loans and Treasury note issues to finance the war effort. Those Treasury notes which did not bear an interest rate depreciated badly against gold and silver and the banknotes of sound banks. Those Treasury notes that did bear an interest rate held their value quite well, and after the war the federal government was able to retire the notes by accepting them as payment for taxes in lieu of gold or silver. Indeed, with the fortunate demise of the Second Bank of the United States during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, the Independent Treasury system was eventually established and functioned well until it was replaced by the Federal Reserve Bank.

MMT would deeply disturb a Jeffersonian. First, the currency being used is not the federal government’s obligations, but a currency that is the monopoly property of a private bank with some quasi-public features. This currency, the Federal Reserve Note, is acceptable for the payment of taxes and has a legal tender status, but it is redeemable in nothing, or better yet it is redeemable in base metal coins. The Federal Reserve Note is a debt, but it bears no interest. Moreover, to create more of the currency, the federal government has to issue bonds as the Federal Reserve Note is a debt-based currency, if more currency is issued it has to be through the mechanism of federal government deficits. This is why the debt ceiling cannot and will not ever work. These are the ingredients of a fiscal witch’s brew to destroy confidence in the currency. Moreover, who will benefit? The new currency created will go to those banks and firms who will have the benefit of using the currency at today’s prices. By the time the currency shows up as wages in the hands of worker, prices for the goods and services these folks purchase will have adjusted up, and most likely at a rate faster than their wage increases. Too much inflation? Raise taxes and these same working folks are hit with a double whammy: higher taxes, increasing prices, and before you know it 1970s era stagflation. The very people the Democrats hope to benefit will instead be ruined. The Jeffersonian solution? “Love of peace, hatred for offensive war, a loathing of public debt, excises, and taxes, tenderness for the liberty of the citizen, jealousy, Argus eyed jealousy of the power of the executive.” I might add to Mr. Randolph’s list of true republican principles the following: end the Federal Reserve system, end fractional reserve lending, restore the Independent Treasury and a metallic based currency, and put an end to all forms of crony capitalism, especially in banking and finance. In brief, a free market where banking, finance, and all industry shoulder their own risks and are regulated by the old common law maxim of do no harm to thy neighbor. Otherwise, the “New Green Deal” will just be more of the same with some added progressive virtue signaling that is every bit as insufferable and phony as Ben Bernanke taking credit for saving the universe.