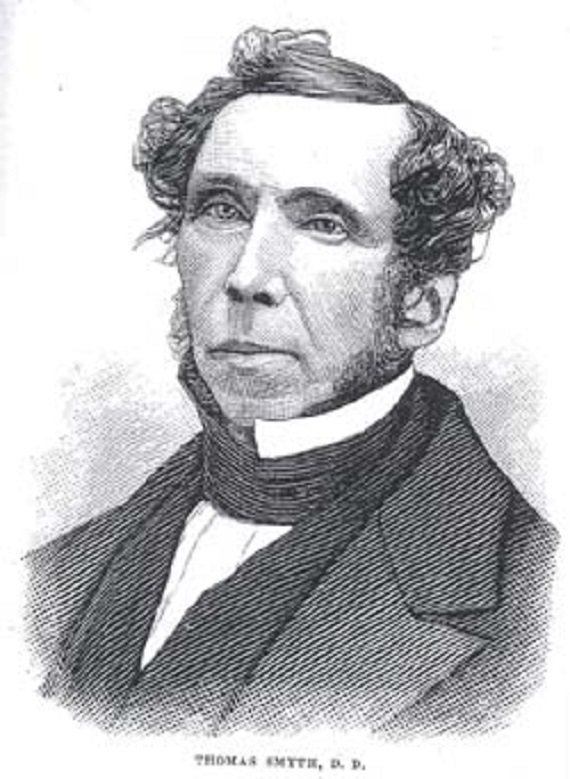

Lately there has been mention of Dr. Thomas Smyth in two Abbeville Institute blog and review posts, namely, “The Theology of Secession” by M. E. Bradford, and “What Lincoln’s Election Meant to the South” by Bradley J. Birzer. Having written about this Charleston clergyman in an upcoming book, I thought our readers might be interested in learning a little more about him.

Thomas Smyth (1808-1873), a native of Ireland, came to America as a young man and attended Princeton Theological Seminary. In 1831 he accepted a call from Second Presbyterian Church in Charleston, South Carolina, where he would serve as pastor for several decades. Upon his arrival in the city he was befriended by James Adger, a wealthy Charleston businessman and a fellow native of Belfast. Smyth soon developed an attachment to Adger’s daughter Margaret and married her in 1832. The Adgers were a devout family, and when Smyth’s brother-in-law James B. Adger returned to Charleston from foreign mission work in 1847, he dedicated his life to “the religious instruction of the negroes in Charleston.” Lamenting an inadequacy in “church accommodations” for them, as well as “a want of suitable instruction,” Adger, Dr. Smyth, and others advocated the establishment of a “separate colored church.” The Episcopalians had already had organized Calvary Church in Charleston for this purpose, and though it initially met with opposition by some of the white citizens, the congregation (which included white members) flourished.

In 1850 Second Presbyterian Church established a mission church for the black people, and then in 1858, with enthusiastic support from Dr. Smyth and members of the Adger family, the mission church was transformed into “a self-sustaining church with white Eldership and members of its own.” Under the leadership of the great preacher John L. Girardeau, the membership increased until it became necessary to build “the largest church edifice in Charleston” to accommodate them. John B. Adger wrote of this church, which was named Zion: “This immense building, costing twenty-five thousand dollars, was all paid for by the white citizens of Charleston, as an expression of their interest in the religious welfare of the colored people…The main floor was occupied by negroes, for whom the preaching was chiefly designed; but there were galleries on three sides facing the pulpit for the white people.”

During the 1850s and earlier Southern clergymen and laity responded to abolitionist attacks on slavery by urging reforms for the institution that would bring it into more conformity with Christian principles. Because of his support of such reforms and his involvement in the establishment of Zion Church, Smyth was sometimes accused of being an abolitionist. Although he likely supported the emancipation movement in Great Britain, he did not espouse such views after adopting South Carolina as his home, probably because no similar program of compensated emancipation had been offered in America. Like John B. Adger, Smyth held the view that “Southern slavery was just a grand civilizing and Christianizing school, providentially prepared,” and that “the two races were steadily and constantly marching onwards and upwards together” to eventual emancipation, when the enslaved race was ready to “graduate.”

Dr. Smyth was an influential writer who published numerous sermons and articles and authored thirty theological books. The degree of “Doctor in Divinity” was conferred on him in 1843 by Princeton Seminary for his “attainments in Theological Learning” and his “labours in the cause of truth and righteousness.” Besides theology, Smyth had active interests in science, medicine, law, art, and literature, and for many years he was a member of Charleston’s Literary and Philosophical Society (also known as the Conversation Club), which Smyth’s biographer described as being comprised of “the most intelligent men of Charleston.” In 1850 Dr. Smyth authored a book entitled The Unity of the Human Races, refuting the theories of Dr. Samuel George Morton of Philadelphia, his protégé Louis Agassiz of Harvard University, and others who believed that the races came from separate origins. Smyth was also a passionate bibliophile, amassing a library of nearly twenty thousand volumes.

After Lincoln’s election in 1860, the South Carolina legislature passed an act calling for a convention to deliberate the issue of secession. Soon afterward, the governor proclaimed a day of humiliation and prayer, and on the appointed day of November 21, Smyth preached one of his most important sermons. Those who are familiar with the writings of the great Presbyterian churchman James Henley Thornwell will recognize echoes of his ideas in it. Concerning the deadly sectional rift between North and South, Thornwell wrote: “The parties in this conflict are not merely Atheists, Socialists, Communists, Red Republicans, Jacobins on the one side, and the friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is a battle-ground, Christianity and atheism the combatants, and the progress of humanity the stake.”

Printed under the title The Sin and the Curse, Smyth’s sermon lamented the death of “this glorious constitutional union,” and identified America’s “the true source of disunion” in the “infidel, atheistic, French Revolution, Red Republican principle” embodied in the egalitarian ideas of the Declaration of Independence. “All men are not born equal,” Smyth contended. “The only equality is that all men are born in sin.” The nation was divided, he argued, because of the influence of a group of Americans who rejected the divine inspiration and infallibility of the Bible, and who developed their own code of morality, or “higher law principle.” Smyth wrote that they were “an overwhelming mass” of

…atheists, infidels, communists, free-lovers, rationalists, Bible haters, anti-christian levelers, and anarchists…[who held] a self-developing morality…[and who decided that] a majority of his creatures can decide for God, and against God, that slavery is, in its essential nature, absolutely sinful; further, that it is so essentially and heinously wicked, that in order to overthrow it, compacts may be broken, and robbery, murder, arson, treason, rebellion and massacre with all the hellish crew of bigotry, hatred, uncharitableness, [and] excommunication… are let loose to devastate and destroy.

They pervert the great doctrines of personal responsibility, liberty of conscience… thought, opinion and…action. This they do by requiring all others to adopt as God’s truth, that which is… beside and contrary to Scripture; and by assuming that they are responsible for the opinions and conduct of other men…And what, we ask, could finally be the result of this higher law—that is, the majority and equality-principle—but anarchy, prodigality, profanity, Sabbath profanation, vice and ungodliness in every monstrous form, and in the end the corruption and overthrow of the Republic, and the erection, upon its ruins, of an absolute and bloody despotism, of which coercion… is the vital principle. An anti-slavery Bible must have an anti-slavery God, and then a God anti-law, order, property and morality; that is no God but ‘THE GOD OF THIS WORLD.’

The “God of this world” as identified in the Bible, is Satan.

Though Dr. Smyth regretted the dissolution of the Union, he believed that it was was necessary for the safety and welfare of the South. On December 24, 1860, a few days after South Carolina seceded, Smyth wrote to a fellow clergyman and expressed the view of most South Carolinians that the platform of the Republican Party was “sectional and destructive to any continued Union with the South.” He added, “I have no sympathy with Secession per se, but be it death, it is better than degradation.”

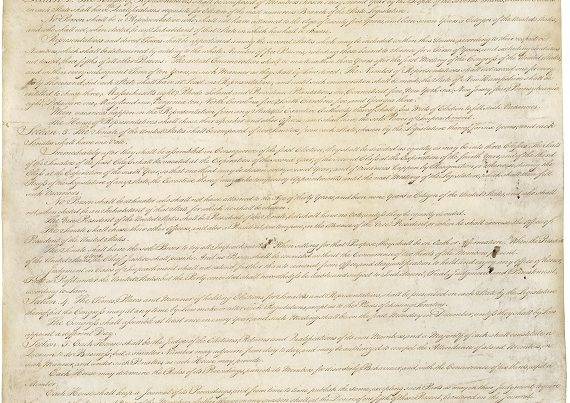

During the secession crisis, Dr. Smyth received numerous letters from concerned friends and colleagues all over the country, and some appealed to him to use his influence to oppose secession. On December 21, 1860, Dr. M. W. Jacobus of the Alleghany Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania wrote to Smyth and pleaded with him to speak out “in behalf of Peace and Union.” Later, in January1861, Dr. Jacobus urged Smyth to “counsel utmost moderation,” and begged him not to “despair of our nation,” adding, “You cleave to the Constitution. Why can we not live together under it as aforetime? Even Mr. Seward declares himself ready to go for an amendment prohibiting any future interference with slavery, where it exists.” Jacobus was referring to the Corwin Amendment, which was introduced in the House of Representatives by Thomas Corwin of Ohio and eventually passed by a two-thirds majority of Congress. It would amend the Constitution to explicitly forbid any interference with the institution of slavery where it already existed, stating, “No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give Congress power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of the State.” The outgoing president James Buchanan supported the amendment, as did William H. Seward and the president elect Abraham After the amendment passed both houses, the ratification process began in the state legislatures, the Ohio General Assembly becoming the first to ratify it. Maryland was next, but the advent of war brought an end to the ratification process.

Once the war began, Dr. Smyth supported the newly formed Confederacy wholeheartedly. A colleague, Dr. Gilbert R. Bracket, wrote that Smyth “espoused the cause of the South” because he believed it was contending for the principles of “civil liberty and free government.”