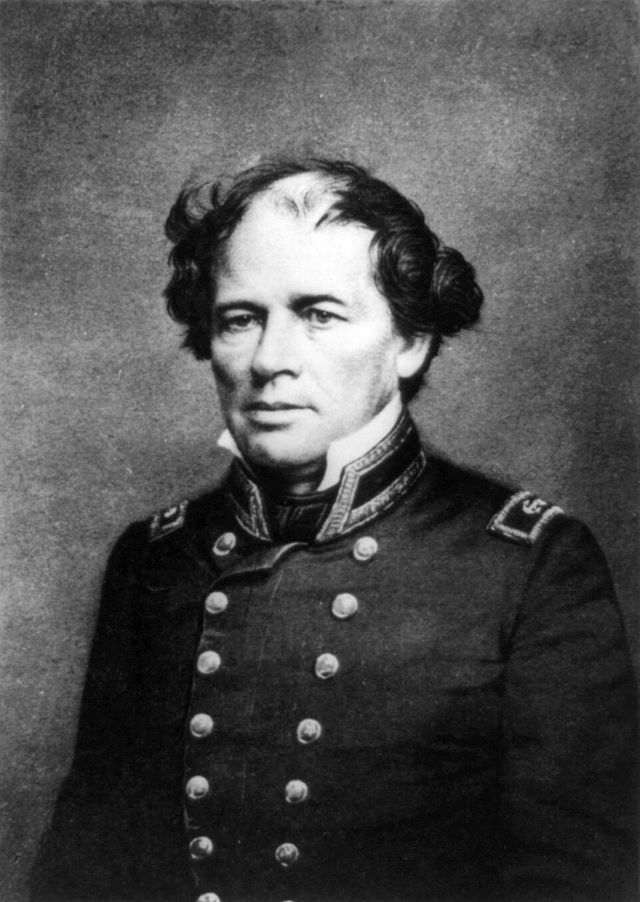

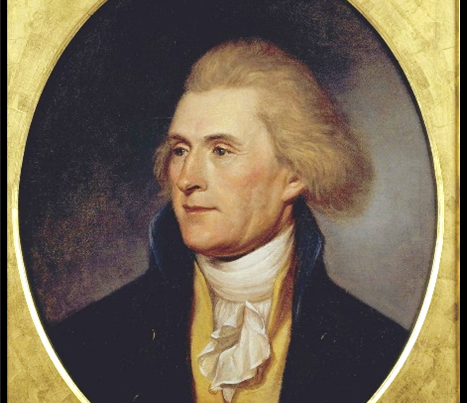

Few Americans know of the great American scientist Matthew Fontaine Maury, and those that do probably do not know of his steadfast devotion to the Confederate States during the War for Southern Independence or his firm commitment to the South and her people. Maury was a native Virginian and his father had once been a teacher to Thomas Jefferson. Maury joined the United States Navy at 19, but after a stagecoach accident left him crippled, he dedicated his life to science, in particular meteorology and oceanography. His work in sea currents, weather patterns, and ocean navigation led to international acclaim. He was possibly the most well-known American on foreign shores, and his The Physical Geography of the Sea (1855) was considered the definitive textbook on oceanography. He was also a humanitarian who proposed to eradicate slavery in the United States through a complex colonization proposal that received little traction either at home or abroad.

When the War began in 1861, Maury resigned his naval commission and joined the Confederate Navy. He was placed in charge of coastal defenses and developed an electrical contact torpedo that effectively curtailed Union naval activity in many Southern ports. He also spent time in Europe pressing for foreign arbitration to end the War. After the War, he accepted a teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute. He died in 1873, exhausted by a world tour on the importance of meteorology.

Below are sections of one of the last pieces he wrote for publication in 1871. It was his view on the causes of the War and a defense of his native soil, Virginia. Following that is an award winning 1939 short documentary on Maury. He was concurrently an American and a Southern hero. The two were long considered and still should be considered synonymous.

In consequence of the Berlin and Milan Decrees, the Orders in Council, the Embargo and the war which followed in 1812, the people of the whole country suffered greatly for the want of manufactured articles, many of which had become necessaries of life. Moreover, it was at that time against the laws of England for any artisan or piece of machinery used in her workshops to be sent to this country. Under these circumstances it was thought wise to encourage manufacturing in New England, until American labor could be educated for it, and the requisite skill acquired, and Southern statesmen took the lead in the passage of a tariff to encourage and protect our manufacturing industries. But in course of time these restrictive laws in England were repealed, and it then became easier to import than to educate labor and skill. Nevertheless the protection continued, and was so effectual that the manufacturers of New England began to compete in foreign markets with the manufacturers of Old England. Whereupon the South said, “Enough: the North has free trade with us; the Atlantic ocean rolls between this country and Europe; the expense of freight and transportation across it, with moderate duties for revenue alone, ought to be protection enough for these Northern industries. Therefore let us do away with tariffs for protection. They have not, by reason of geographical law, turned a wheel in the South; moreover, they have proved a grievous burden to our people.” Northern statesmen did not see the case in that light; but fairness, right and the Constitution were on the side of the South. She pointed to the unfair distribution of the public lands, the unequal dispensation among the States of the Government favor and patronage, and to the fact that the New England manufacturers had gained a firm footing and were flourishing. Moreover, peace, progress and development had, since the end of the French wars, dictated free trade as the true policy of all nations. Our Senators proceeded to demonstrate by example the hardships of submitting any longer to tariffs for protection. The example was to this effect:—The Northern farmer clips his hundred bales of wool, and the Southern planter picks his hundred bales of cotton. So far they are equal, for the Government affords to each equal protection in person and property. That’s fair, and there is no complaint. But the Government would not stop here. It went further—protected this industry of one section and taxed that of the other; for though it suited the farmer’s interest and convenience to send his wool to a New England mill to have it made into cloth, it also suited in a like degree the Southern planter to send his cotton to Old England to have it made into calico. And now came the injustice and the grievance. They both prefer the Charleston market, and they both, the illustration assumed, arrived by sea the same day and proceeded together, each with his invoice of one hundred bales, to the custom-house. There the Northern man is told that he may land his one hundred bales duty free; but the Southern man is required to leave forty of his in the custom-house for the privilege of landing the remaining sixty. It was in vain for the Southerner to protest or to urge, “You make us pay bounties to Northern fishermen under the plea that it is a nursery for seamen. Is not the fetching and carrying of Southern cotton across the sea in Southern ships as much a nursery for seamen as the catching of codfish in Yankee smacks? But instead of allowing us a bounty for this, you exact taxes and require protection for our Northern fellow-citizens at the “expense of Southern industry and enterprise.” The complaints against the tariff were at the end of ten or twelve years followed by another compromise in the shape of a modified tariff, by which the South again gained nothing and the North everything. The effect was simply to lessen, not to abolish, the tribute money exacted for the benefit of Northern industries.

Fifteen years before the war it was stated officially from the Treasury Department in Washington, that under the tariff then in force the self-sustaining industry of the country was taxed in this indirect way in the sum of $80,000,000 annually, none of which went into the coffers of the Government, but all into the pocket of the protected manufacturer. The South, moreover, complained of the unequal distribution of the public expenditures; of unfairness in protecting, buoying, lighting and surveying the coasts, and laid her complaints on grounds like these: for every mile of sea-front in the North there are four in the South, yet there were four well equipped dockyards in the North to one in the South; large sums of money had been expended for Northern, small for Southern defences; navigation of the Southern coast was far more difficult and dangerous than that of the Northern, yet the latter was better lighted; and the Southern coast was not surveyed by the Government until it had first furnished Northern ship-owners with good charts for navigating their waters and entering their harbors.

Thus dealt by, there was cumulative dissatisfaction in the Southern mind towards the Federal Government, and Southern men began to ask each other, “Should we not be better off out of the Union than we are in it?”—nay, the public discontent rose to such a pitch in consequence of the tariff, that nullification was threatened, and the existence of the Union was again seriously imperiled, and dissolution might have ensued had not Virginia stepped in with her wise counsels. She poured oil upon the festering sores in the Southern mind, and did what she could in the interests of peace; but the wound could not be entirely healed; Northern archers had hit too deep.

The Washington Government was fast drifting towards centralization, and the result of all this Federal partiality, of this unequal protection and encouragement, was that New England and the North flourished and prospered as no people have ever done in modern times. Scenes enacted in the Old World, twenty-eight hundred years ago, seemed now on the eve of repetition in the new. About the year 915 B. C., the twelve tribes conceived the idea of making themselves a great nation by centralization. They established a government which, in three generations, by reason of similar burdens upon the people, ended in permanent separation. Solomon taxed heavily to build the temple and dazzle the nation with the splendor of his capital; his expenditures were profuse, and he made his name and kingdom fill the world with their renown. He died one hundred years after Saul was anointed, and then Jerusalem and the temple being finished, the ten tribes— supposing the necessity of further taxation had ceased—petitioned Rehoboam for a reduction of taxes, a repeal of the tariff. Their petition was scorned, and the world knows the result. The ten tribe seceded in a body, and there was war; so thus there remained to the house of David only the tribes of Benjamin and Judah. They, like the North, had received the benefit of this taxation. The chief part of the enormous expenditures’ was made within their borders, and they, like New England, flourished and prospered at the expense of their brethren….

This long list of grievances does not end here. The population of the North had, by reason of the vast numbers of foreigners that had been induced to settle there, become so great that the balance of power in Congress was completely destroyed. The Northern people became more tyrannical in their disposition, Congress more aggressive in their policy. In every branch of the Government the South was in a hopeless minority, and completely at the mercy of an unscrupulous majority for their rights in the Union. Emboldened by their popular majorities on the hustings, the master-spirits of the North now proclaimed the approach of an “irrepressible conflict” with the South, and their representative men in Congress preached the doctrine of a “higher law,” confessing that the policy about to be pursued in relation to Southern affairs was dictated by a rule of conduct unknown to the Constitution, not contained in the Bible, but sanctioned, as they said, by some higher law than the Bible itself. Thus finding ourselves at the mercy of faction and fanaticism, the Presidential election for 1860 drew nigh. The time for putting candidates in the field was at hand. The North brought out their candidate, and by their platform pledged him to acts of unfriendly legislation against us. The South warned the North and protested, the political leaders in some of the Southern States publicly declaring that if Mr. Lincoln, their nominee, were elected, the States would not remain in the Union. He was truly a sectional candidate. He received no vote in the South, but was, under the provisions of the Constitution, duly elected nevertheless; for now the poll of the North was large enough to elect whom she pleased.

When the result of this election was announced, South Carolina and the Gulf States each proceeded to call a convention of her people; and they, in the exercise of their inalienable right to alter and abolish the form of government and to institute a new one, resolved to withdraw from the Union peaceably, if they could. They felt themselves clear as to their right, and thrice-armed; for they remembered that they were sovereign people, and called to mind those precious rights that had been solemnly proclaimed, and in which and for which we and our fathers before us had the most abiding faith, reverence and belief. Prominent among these was, as we have seen, the right of each one of these States to consult her own welfare and withdraw or remain in the Union in obedience to its dictates and the judgment of her own people. So they sent commissioners to Washington to propose a settlement, the Confederate States offering to assume their quota of the debt of the United States, and asking for their share of the common property. This was refused.

In the meantime Virginia assembled her people in grand council too; but she refused to come near the Confederate States in their councils. She had laid the corner-stone of the Union, her sons were its chief architects; and though she felt that she and her sister States had been wronged without cause, and had reason, good and sufficient, for withdrawing from a political association which no longer afforded domestic tranquility, or promoted the general welfare, or answered its purposes, yet her love for the Union and the Constitution was strong, and the idea of pulling down, without having first exhausted all her persuasives, and tried all means to save what had cost her so much, was intolerable. She thought the time for separation had not come, and waited first to try her own “mode and measure of redress;” she considered that it should not be such as the Confederate States had adopted. Moreover, by standing firm she hoped to heal the breach, as she had done on several occasions before. She asked all the States to meet her in a peace congress. They did so, and the North being largely in the majority, threw out- Southern propositions and rejected all the efforts of Virginia at conciliation. North Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas all remained in the Union, awaiting the action of our State, who urged the Washington Government not to attempt to coerce the seceded States, or force them with sword and bayonet back into the Union—a thing, she held, which the charter that created the Government gave it no authority to do.

Regardless of these wise counsels and of all her rightful powers, the North mustered an army to come against the South; whereupon, seeing the time had come, and claiming the right which she had especially reserved not only for herself, but for all the States, to withdraw from the Union, the grand old Commonwealth did not hesitate to use it. She prepared to meet the emergency. Her people had already been assembled in convention, and they, in the persons of their representatives, passed the Ordinance Of Secession, which separated her from the North and South, and left her alone, again a free, sovereign and independent State. This done, she sounded the notes of warlike preparation. She called upon her sons who were in the service of the Washington Government to confess their allegiance to her, resign their places, and rally around her standard. The true men among them came. In a few days she had an army of 60,000 men in the field; but her policy was still peace, armed peace, not war. Assuming the attitude of defence, she said to the powers of the North, “Let no hostile foot cross my borders.” Nevertheless they came with fire and sword; battle was joined; victory crowned her banners on many a well-fought field; but she and her sister States, cut off from the outside world by the navy which they had helped to establish for the common defence, battled together against fearful odds at home for four long years, but were at last overpowered by mere numbers, and then came disaster. Her sons who fell died in defence of their country, their homes, their rights, and all that makes native land dear to the hearts of men.