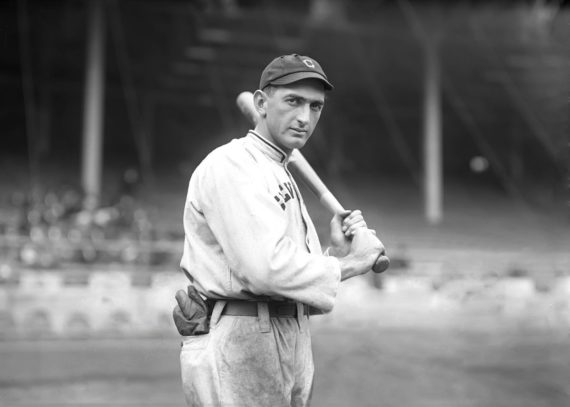

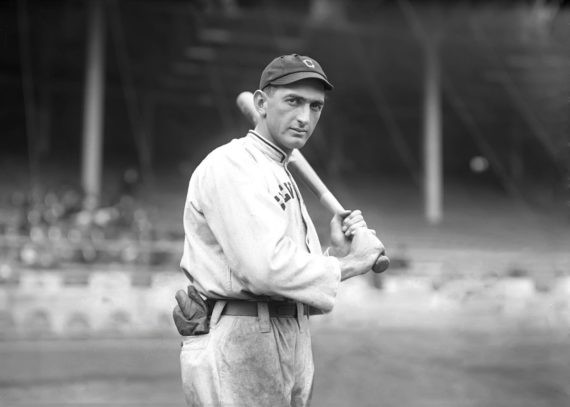

Two of the poems I most admire are very short. One is simply a name – Shoeless Joe Jackson. Read it aloud and feel the assonance and alliteration. The other is a phrase Say it ain’t so, Joe, delivered sadly, with its final rhyme. There is a mythic quality in both of these poems.

The name, Shoeless Joe Jackson; the actual historic figure born in the rural South; his bat, Black Betsy, and his role in the 1919 Black Sox Scandal; the wounded plea of a small boy on the courthouse steps; and baseball itself-are all the stuff of mythology. And mythology is sort of a hanging curveball for writers and film-makers.

Born in Pickens County, South Carolina, around 1888, give or take a year (the Jackson family Bible, which recorded such events, was destroyed in a fire) Joe Jackson, by all accounts, was a remarkable natural athlete.

Donald Gropman’s 1979 biography Say It Ain’t So, Joe! contains most of the details of Jackson’s life, although it is scarcely an unbiased account. Jackson was Gropman’s immigrant father’s favorite player, and although the author spent extensive time with interviews and yellowed newspaper clippings-his work is essentially a tall tale with tragic overtones, a glorification of Jackson’s abilities and a defense of a player whose illiteracy and Southern background led to shabby treatment from the press even before the Scandal. Gropman is unwavering in his belief that Jackson’s claim (supposedly spoken the day before he died in 1951) “I don’t deserve this thing that’s happened to me” was valid.

Gropman is also completely unskeptical of the legend of Jackson’s fabled bat, “his talisman,”: Black Betsy. The bat, presumably the Southern boy’s most prized tool, was a gift to Joe when he was fifteen or sixteen from a Charley Ferguson, “the local batmaker” who “selected his best billet of seasoned lumber…a long four-by-four which he had cut from the north side of a hickory tree a year or so before.” After “clamping it in a lathe and fashioning the pale white wood into a bat, Charley rubbed it in a coat or two of tobacco juice because he knew Joe favored black bats.” Throughout his playing days, fans would yell, “Give ’em Black Betsy, Joe!” and Jackson would respond with the line drives his fans called “blue darters.” Stories surfaced, if not during Jackson’s playing days at least later, that Joe reportedly took his bat to bed with him every night, as well as down South each winter because he believed she preferred the warmth. Jackson, when he was in his early fifties, presumably gave the bat to the mayor of Greenville, South Carolina (where he had grown up and where he lived most of his life). The bat, thus according to legend, went unbroken through countless Mill League, minor league, and exhibition games. The “Black Betsy” story was recast by Bernard Malamud in his 1952 novel The Natural as the main character Roy Hobbs (a composite of Joe Jackson, Babe Ruth, and Eddie Waitkus) travels with his bat “Wonderboy” fashioned from a tree struck by lightning. To my knowledge and that of Baseball Digest, whom I contacted, those are the only two recorded instances of a baseball bat receiving a “Christian” name.

Other aspects of Jackson’s youth and life are less fanciful. His tenant farmer father and his three brothers all worked in a Brandon Mill, South Carolina, sawmill until the father moved to Pelzer, south of Greenville where he found a job in the engine room of a new cotton mill. Jackson himself began working seventy-hour weeks in the mills at age six. Educational opportunities were non-existent. The mill owners sponsored baseball teams to create a “sense of community” -actually to provide local entertainment to appease employees and to discourage them from moving their families from the shanties they rented and away from the Company Store.

Jackson’s abnormally long arms, huge hands, and natural playing ability (he could hit, run, field and throw) made him a star on the mill teams, and supposedly his brothers “passed the hat” into which spectators threw coins whenever Joe got a timely hit or made a stellar catch or throw. (Jackson did some pitching, but, after one of his deliveries struck a batter breaking his arm, he converted to outfielder). The Greenville News in 1900 commented favorably on the fact that “goodly sums of money” were being bet on the games, interpreting this as proof of baseball’s growing popularity.

According to Gropman, Jackson acquired the “Shoeless Joe” nickname around 1908. It was not a case of a country boy unused to shoes preferring to play in his bare feet. Supposedly

Jackson, attempting to break in a new pair of spikes, the next day experienced painful blisters which would not permit him to wear footwear. In the scheduled game against an Anderson, South Carolina, mill team, Jackson played in his stocking feet and homered, and, as he rounded third, a fan shouted, “Oh, you shoeless sonofabitch!” The baseball writer for the Greenville News, Scoop Latimer, coined “Shoeless Joe Jackson” in his column the next day much to his readers’ delight.

Jackson’s major league playing time extended from 1908-1920 although the equivalent of full seasons in the majors spanned only 8.2 years, not thirteen as has often been given. He was purchased by Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics, had difficulty adjusting to the northern city and his teammates, and spent one season with Savannah in the Sally League and another with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern League. (Jackson felt comfortable and found his teammates more hospitable and less given to pranks in the southern cities). In 1910, Connie Mack traded the talented but unpredictable Jackson (in 1908 he left the parent club to return to Greenville) to the Cleveland Indians, and in 1915 he was traded by Cleveland to the Chicago White Sox. His .356 lifetime batting average is the third highest in major league history behind Ty Cobb (who consistently bested Jackson in the batting races) and Rogers Hornsby and currently still ahead of Wade Boggs. A rather suspect story claims that Babe Ruth copied Jackson’s swing because it was the smoothest he ever observed, while Ty Cobb is on record as describing Jackson as “the best natural hitter he ever saw.”

In Chicago, Jackson played for owner Charlie Comiskey, who savored the power of “indentured servitude”- baseball’s reserve clause binding players to the team that held their contracts (prior to Curt Flood’s legal case a half-century later). Comiskey was steadfast in his view players should not be overpaid. Jackson’s highest salary with the White Sox was $6,000 in 1919. Characteristic of Comiskey’s tight-fisted strategies (except in the case of the college-educated second baseman Eddie Collins who earned $10,000 in 1919) was his handling of star pitcher Eddie Cicotte, master of the knuckler (involving specially-prepared imbalanced baseballs) and the now illegal shine ball (involving paraffin on the pant leg). Cicotte was promised a bonus if he won 30 games. When the pitcher reached 29 wins, he was removed from the rotation (the team had already clinched the pennant, and the argument given was that Cicotte needed to be rested for the World Series).

Comiskey’s role as a symbol of insensitive capitalism became pivotal for at least three contemporary writers; the historian of the 1919 Series Scandal Eliot Asinof in his 1962 investigative account Eight Men Out; the socially conscious author (Union Dues) and screenwriter-director (The Return of the Seacaucus Seven and Matewan) John Sayles, who scripted and directed the film version of Eight Men Out and who cast Asinof in a small role as president of the National League; and playwright Lawrence Kelly who wrote the 1976 off-Broadway drama Out For them, Shoeless Joe Jackson is forever a doomed innocent, mistreated and held in low regard by his employer, and susceptible to the money-making pleas of a few select teammates and the mushrooming complexity of a Watergate/Irangate-like conspiracy.

Generally accepted details of the fix disclose the scheme was initiated by first baseman Chick Gandel, who, encouraged initially by minor gambling elements and finally supported by kingpin Arnold Rothstein, easily recruited Cicotte, who was anxious about his financial security after his playing days ended. Six other members of the White Sox, including Jackson, were approached. In the Series, Jackson collected twelve hits, batted .375, and made no errors in the field. Later, after the Cincinnati Reds’ victory over a Sox team that some experts have claimed was as formidable as the 1927 Yankees, Jackson received $5,000. Gropman in his biography claims Jackson attempted to reveal the plot to Comiskey, was denied access to the owner, and was later told by the club to keep the money. During the 1920 season, an investigation prompted by sportswriters led to three of the eight confessing before a grand jury. Jackson, supposedly with assurances and on the advice of Comiskey’s lawyer, signed a confession with his “X.”

The “say it ain’t so, Joe” line first appeared in a September 30,1920 article by Hugh Fullerton in The New York Evening World the day after Jackson’s grand jury appearance. According to Fullerton:

While he related the sordid details to the stem faced, shocked men, there gathered outside the big stone building a group of boys….After an hour, a man, guarded like a felon by other men, emerged from the door. He did not swagger. He slunk along between his guardians, and the kids, with wide eyes and tightened throats, watched, and one, bolder than the others, pressed forward and said “It ain’t so, Joe, is it?” Jack-son gulped back a sob, the shame of utter shame flushed his brown face. He choked an instant, “Yes Kid, I’m afraid it is,” and the world of faith crushed around the heads of the kids. Their idol lay in the dust, their faith destroyed. Nothing was true, nothing was honest. There was no Santa Claus. Then, and not until then, did Jackson, hurrying away to escape the sight of the faces of the kids, understand the enormity of what he had done.

According to Gropman, Fullerton’s account was mere fiction, the fantasy of a biased, opportunistic reporter who had, in 1911, predicted Jackson “would fail in the major leagues because he was ignorant” and who delighted in presenting as truth the old yarn that “the club was forced to hog tie him to get shoes on him as he wailed he couldn’t hit unless he could get toe holds.” Gropman provides Jackson’s assertion that, when he left the courthouse, the only words exchanged were between himself and a deputy and that no member of the waiting crowd spoke to him. In any case “Say It Ain’t So, Joe” became fifty years later the title of a hit song by Murray Head.

In Malamud’s The Natural, the fictional Roy Hobbs is shot in a hotel room by a deranged woman (as real-life Phillies star Eddie Waitkuswas). Finally years later Hobbs, now in his mid-thirties, enters the majors and crushes home runs with his Black Betsy-like bat named Wonderboy. A bout of gluttony sends him to the hospital during a crucial time in the season (the recasting of a Babe Ruth story), and, prior to the pennant playoff game, Hobbs is tempted with a bribe by the club owner and his gambling associate to throw the contest.

Hobbs, after deciding to win the game with a last-inning hit, is struck out. The cloud of conspiracy surfaces, and on the last page of the novel, a boy thrusts a newspaper at Hobbs and asks, “Say it ain’t true, Roy.” The source for the line is obvious although Malamud’s use of assonance in “true’/’Roy” is less successful. The Barry Levinson-directed film version with Robert Redford as Roy Hobbs has a positive, mythic ending as Hobbs wins the playoff game with a god-like home run that knocks out a light tower, showering the field with sparks, retires (his old wound so dictating), and spends his remaining years with the Good Woman (Glenn Close), who unbeknownst to him always supported Roy, and their son. The real Joe Jackson had no children, but his 1908 marriage to Katherine Wynn did last 43 years until his death in 1951.

In the February 1921 trial, held five months after the grand jury indictments, the eight players were acquitted largely because evidence including the signed confessions had been stolen and was thus unavailable. Speculation exists that the theft was planned jointly by Comiskey and Rothstein, strange bedfellows working together to protect their own interests. Supporting this charge is the fact that, in 1924, when Jackson filed a lawsuit against Comiskey and the White Sox to collect two years salary, amounting to $18,000, on his contract, his confession reappeared and was used against him by the defense attorneys who argued the slugger had voided his contract when he implicated himself in the fix. Jackson lost the case as the judge not only overturned the jury verdict but sentenced Jackson to a brief jail term for perjury.

In November 1920, two weeks after he had been named Commissioner of Baseball with absolute power by the owners, former District Court Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis made his feelings on the eight players known: “There is absolutely no chance for any of them to creep back into Organized Baseball. They will be and remain outlaws….It is sure that the guilt of some of them at least will be proved.” The day after the jury verdict was reached, Landis-certainly to the pennant-minded Comiskey’s dismay–issued his sentence: “Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ball game; no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are planned and discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.” Landis’s announcement sealed the fates not only of those who followed through on the conspiracy, but also of Buck Leonard, who supposedly knew what certain teammates were planning but who played as well as he personally could in the Series, and of Jackson.

Stories persisted-and have been wrongly validated by the ending of Sayles’s Eight Men Out-that, after the Landis ban, Jackson played under assumed names where he could on the fringes of baseball, collecting $5 a game and $7.50 for a double-header. In the final scene of Eight Men Out, a sparse crowd watches an aged Jackson (D.B. Sweeney) slam a double; a fan claims he thinks that’s Shoeless Joe, but another spectator, an unrecognized Buck Weaver (John Cusack), affirms sadly and defiantly, “No, that’s not him.” According to Gropman, however, after his expulsion from the majors, until age 45, Jackson played under his own name in the semiprofessional South Georgia League and in promotional contests, where he was advertised in posters and warmly treated by fans. Later Jack-son and his wife operated a Greenville, South Carolina, dry-cleaning business called the Savannah Valet Service, employing over twenty people. The house in Greenville where Jackson lived and where he suffered his fatal heart attack in 1951 still stands. Older residents of the area recall his playing ball on the streets on weekends with neighborhood kids until the last days of his life.

Vestiges and usages of the Joe Jackson myth in popular culture are many. Chicago writer Nelson Algren (The Man with the Golden Arm, Walk on the Wild Side) contributed a poem: For Shoeless Joe is gone, long gone A long yellow glass-blade between his teeth And the bleacher shadows behind him.

In the Broadway musical Damn Yankees (Tab Hunter in the film version playing the role of Joe Hardy, the old man who traded his soul to become a major league star), one of the strongest numbers is “Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, Mo.” A 1950’s television series “On Trial” (with depictions of the trials of infamous 20th century personages) included an episode on Jackson with a scene where a tattered newsboy runs up to Joe on the witness stand and utters the famous five-word plea. Gropman and Asinof contributed non-fiction prose accounts and Malamud with The Natural a fictional one. Film versions include The Natural, Eight Men Out, and, most recently, Field of Dreams.

An American Indian writer whose works often-but not always-revolve around baseball (The Iowa Baseball Conspiracy, The Thrill of the Grass), W.P. Kinsella, first presented the tale of a ghostly Jackson appearing on a baseball diamond built in an Iowa cornfield in a short story “Shoeless Joe Jackson Comes to Iowa,” which appeared initially in the literary magazine Aurora and later in a 1980 collection Shoeless Joe Jackson Comes to Iowa. In 1982 the 17-page short story grew into the novel Shoeless Joe, which served as the source for the 1989 film Field of Dreams—directed by Phil Alden Robinson with Kevin Costner, James Earl Jones, and, as a right-hand hitting Joe Jack-son, Ray Liotta. The mood of both the novel and the motion picture is wistful. A baseball fan, dreamer, and former student-turned farmer–(played by Costner and named in the film, appropriately enough, Kinsella) is told by a benevolent voice to “build it and he will come.” The forces behind the voice offer Jackson heavenly reinstatement in baseball and effect a reconciliation between a celebrated hermit writer and humanity, and between Kinsella and his deceased father.

Although at least one reviewer, Harlan Jacobsen in Film Comment, criticized the film’s Capra-like spirit and the substituting of a black writer (Jones) for the J.D. Salinger of the novel, the film was a summer success reinitiating interest in and sympathy for Shoeless Joe Jackson. Previous efforts and petitions to have Jackson reinstated during the terms of Landis and Commissioner Happy Chandler had been dismissed, but the film’s popularity led to fresh attempts. A June 12, 1989 Sports Illustrated article by Nicholas Dawidoff questioned how Jackson with his .356 lifetime batting average could be prohibited from inclusion in Baseball’s Hall of Fame, petitions circulated in movie theaters, and state legislators pursued motions.

Connected in the summer of 1989 to the resurgence of Jack-son as an entertainment icon was the Pete Rose case, in which baseball’s most proficient all-time base hit leader faced removal from the game on gambling charges, and the news stories and commentaries often included mention of Jackson and the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, the incident that had led professional baseball and its Commissioner to their position on players gambling on games. The decision on Rose’s status rested with a former literary scholar and President of Yale, Commissioner Bart Giamatti.

Shorty after the lifetime banning of Rose, Giamatti reviewed an appeal by South Carolina State Senator Ernest Passailaigue requesting the reinstatement of Joseph Jefferson Jackson. As might be expected from a man whose published works included Exile and Change in Renaissance Literature, Play of Double Senses: Spenser’s Faerie Queen, and a reflection on baseball Take Time for Paradise, written just before his death, Giamatti’s response, quoted in the August 11, 1989 issue of The New Times, read, “I share the view that a resurrection by me of the case today would not be appropriate” as he “did not wish to play God with history.” Perhaps for the academically-trained and inclined Giamatti, Joe Jackson and Pete Rose were variations of Spenser’s Red Cross Knight, who would have to face the consequences of encounters with any of the Seven Deadly Sins, and on the concept of noble, tragic human freedom that Giamatti defined so verbosely and abstractly in Take Time for Paradise: “Is not freedom the fulfillment of the promise of an energetic, complex order? Clearly I believe the answer is yes, and clearly, therefore, I believe we cherish as Americans a game wherein freedom and reunion are both possible. Baseball fulfills the promise America made itself to cherish the individual while recognizing the overarching claims of the group.

The “group,” one would assume, is not just the team and the opposing players but the fans, the writers, and all who participate in the spectacle. Giamatti continues, “It sends its players out (from home plate around the bases) in order to return again, allowing all the freedom to accomplish great things in a dangerous world (of strikeouts, tags and caught fly balls).” (One might also add of gamblers.) “So baseball restates a version of America’s promises every time it is played. The playing of the game is a restatement of the promises that we can all be free, that we can

all succeed.”

The freedom of which Giamatti writes, one would guess, is not simply of open spaces but of the capability to choose action. He continues: “If we have known freedom, then we love it; if we love freedom, then we fear, at some level (individually or collectively), its loss. And then we cherish sport. As our forebears did, we remind ourselves through sport of what, here on earth, is our noblest hope. Through sport, we re-create our daily portion of freedom, in public.” I suspect that the “fearful” aspect of freedom for Giamatti was not simply the momentary decision to swing at a bad pitch or turn the wrong way on a fly ball but, at least in the cases of Jackson and Rose, darker, available choices of which others must be warned. The case of Jackson includes a historic precedent involving the consequences of an act of freedom judged, one that has become the basis of an essential principle in the mythic and moral makeup of the sports universe.

The legend and legacy of Shoeless Joe Jackson-revolving around the colorful name, the playing prowess, and the special bat–along with the controversy over the extent of his involvement in the 1919 Black Sox affair now constitute more than the problem of whether Jackson should be posthumously elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In a way, he is already there. Anyone who has visited Cooperstown knows there is more to the structure than the room where the plaques of Hall of Famers are located. There are mementos not just of distinguished careers, but of passing successes—large photos of Roger Maris hitting a home run in 1961 and of Harvey Haddix throwing a pitch during the twelve perfect innings of the game against the Milwaukee Braves that he eventually lost. Planned is a new exhibit with items from baseball movies to include the replica of Black Betsy Sweeney used when he portrayed Shoeless Joe in Eight Men Out, Jackson’s legacy is both lyrical and poignantly symbolic. It includes images of dueling, diverse examples of authoritarian exploitation, prejudice in action, stem justice deserved and extracted, injustice perpetrated, the possibility of forgiveness and resurrection, and the persistence of fantasy and myth for artists continually to re-create—all this derived from a Southerner with special, splendid athletic gifts who never learned to read or write.

This article was originally published in the Third Quarter 1990 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.