Illinois has been known as the “Land of Lincoln” for the past sixty years . . . the state legislature having officially adopted the motto in 1955, but a century prior to that most residents of the state’s sixteen southern counties would certainly have objected to the term. That area of Illinois has been called “Little Egypt” or merely “Egypt” since the early 1800s, with town names such as Cairo, Karnak and Thebes dotting the landscape. While there are conflicting stories concerning the origin of the nickname, “Egypt” was definitely pro-Southern territory in the Nineteenth Century, with a majority of the area’s settlers having migrated there from various Southern states, and many of them having brought their slaves with them. Even though Illinois had been admitted to the Union as a “free state‘ in 1818, an exception was granted to those who had owned slaves or who had employed indentured servants prior to statehood, most of whom were in “Egypt” where many worked in the area’s coal and salt mines. Elsewhere in the state, however, other slave-related activities continued to exist even after Illinois was admitted as the 21st state, such as the practice known as the “reversed underground railroad” in which a large number of free African-Americans were kidnapped throughout Illinois and taken South to be sold as slaves up until just prior to the War Between the States. One of the major “stations” for this “railroad” was Hickory Hill, the 30,000-acre plantation of John H. Crenshaw who had originally come to “Egypt’s” Gallatin County from North Carolina. Crenshaw owned over 700 slaves, many of whom worked in Crenshaw’s salt mines, and he was one of the wealthiest citizens of Illinois, where his taxes provided a seventh of the state’s total revenue. In 1840, Illinois State Representative Abraham Lincoln was a guest at the Crenshaw mansion when he traveled to Gallatin County to take part in some political debates in nearby Shawneetown. Lincoln also attended a ball on the second floor of the mansion in honor of the debates, an affair that took place just below the third-floor cells where Lincoln’s host imprisoned those who were soon to be transported South and sold as slaves.

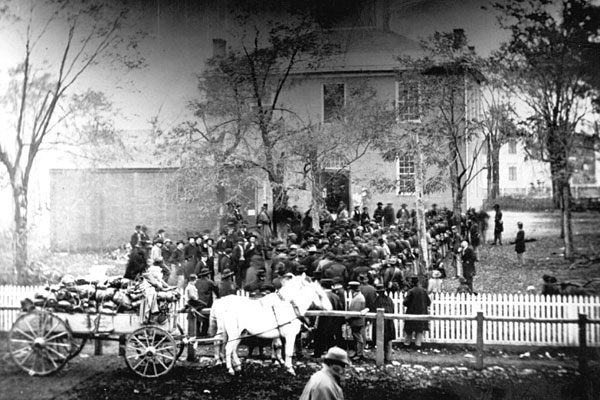

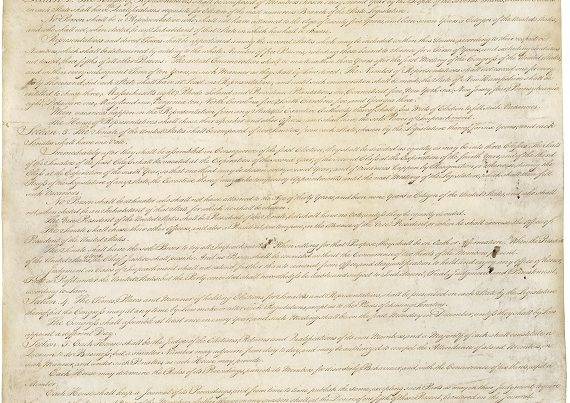

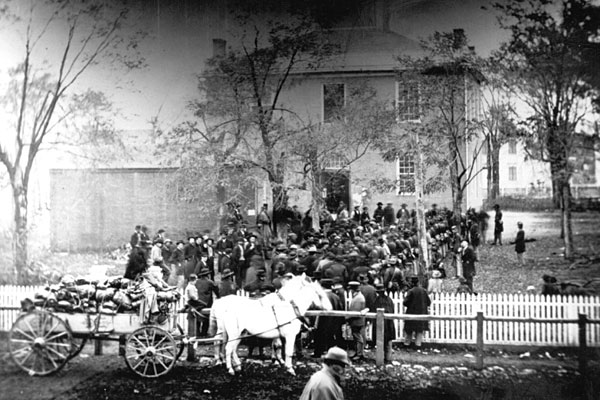

Illinois had also enacted its so-called “Black Laws” in 1819 which remained in effect until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Under these laws, the rights of all African-Americans in the state were severely restricted; they could not vote, bring an action or testify against a white person in court, gather in groups of more than three persons, serve in a state militia or possess firearms. Furthermore, if a person of color failed to carry an official “Certificate of Freedom,” he or she would be considered a runaway slave and treated as such. These laws also ruled that no free black person from another state would be allowed to remain in Illinois for more than ten days and if they did so, they would be subject to arrest, a $50 fine and deportation. The Senatorial elections of 1858 in Illinois were held under these culturally and politically combustive conditions, as well as the darkening clouds of sectional strife which were gathering over the entire nation. In Illinois, the newly formed Republican Party pitted their recently converted Whig politician, Abraham Lincoln, against the popular Democrat incumbent, Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Of course, voters would have to wait until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913 before they could vote directly for U. S. senators. Prior to that time, the members of the U. S. Senate were selected by their respective state legislatures, and in Illinois the vote of the General Assembly’s twenty-five senators and seventy-five representatives would decide between Douglass and Lincoln. Therefore, the famous series of Lincoln-Douglass debates were aimed at the election of the eighty-seven open seats in the General Assembly, with Douglass vowing to “trot him (Lincoln) down to Egypt” where he would challenge Lincoln to defend his anti-slavery views. The Republicans actually gained a 14,000-vote advantage in the state-wide elections, but in “Egypt” thirteen of the area’s sixteen counties went Democratic by over seventy-five per cent, with the remaining three at over fifty-five per cent. The end result saw the Democrats winning forty-six of the General Assembly races, and Douglass being returned to the Senate.

Two years later, in the presidential elections of 1860, with the Democrats split between three national candidates, Douglas, John C. Breckinridge and John Bell, Lincoln was elected with less than forty per cent of the popular vote. Lincoln did win a bare majority of the popular vote in his home state of Illinois (50.7%), sufficient to give him the state’s eleven electoral votes, but in “Egypt,” the results were about the same as what they had been in 1858, with fifteen of the area’s sixteen counties casting over sixty-five per cent of their votes for Democratic candidates, mainly Douglas, and nine of those counties giving over seventy-five per cent of their votes to the Democrats. Prior to Lincoln’s election, an organization called the Knights of the Golden Circle had been active throughout “Egypt” . . . this was a pro-Southern group that supported a confederation of not only all slave-holding states and areas within the United States, but all other Western-Hemisphere nations in which slavery was allowed. After the start of the War, “Egypt” remained a pro-Southern stronghold, and resolutions to secede from the state were proposed in 1861, with actual Ordinances of Secession being drawn up in some of the counties. These overt moves were thwarted, however, by the presence of Illinois state troops under the command of Brigadier General Benjamin M. Prentiss, who had also been sent to Cairo to blockade the Mississippi River and help coerce neighboring Kentucky into remaining in the Union. The majority of “Egypt’s” residents still remained in opposition to the Lincoln Administration throughout the War, with many in the area becoming “Peace Democrats,” also known as “Copperheads” who were followers of Congressman Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, and later as active supporters of General George B. McClellan’s presidential campaign in 1864. Others, however, took a more militant stance by going South to serve in the Confederate armed forces, with one group from Jackson and Williamson Counties known as the “Illinois Rebels” traveling en masse to Tennessee where they joined other Southern sympathizers from Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri and Pennsylvania to form Company “G” of the 15th Tennessee Infantry Regiment, a unit which saw heavy action at both the battles of Pittsburg Landing in Tennessee and Chickamauga in Georgia.

=Moving the calendar ahead to the next century, we have another “Egyptian” who also found his place in the South, the author Stanley Preston Kimmel from Perry County in the upper tier of “Egypt’s counties. Kimmel was born on June 12, 1894, in the coal mining town of DuQuoin where his father operated a lumber business. He left Illinois to study law at the University of Southern California, but then sailed to Europe in 1916 to serve in World War One as an ambulance driver for the French Army. After America’s entry into the War Kimmel returned to America, but was later sent back to Europe as a U. S. Navy pilot. In the years following the War, Kimmel wrote three books of poems and essays about his travels through Europe and the Orient, “The Strange Voyage,” “Crucifixion” and “Leaves on the Water.” While in France during the early 1920s, he also became friends with such American literary giants as Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Kimmel finally returned to America and lived in New Orleans for several years, working first as a reporter for the Times-Picayune and then as the editor of New Orleans Life Magazine. It was in New Orleans in 1926 that Kimmel married Blanche Ethel Vignes, with whom he ultimately shared a grave at the Metairie Cemetery in that city following his death in Sarasota, Florida, on July 28, 1982.

Prior to his final residence in Florida, Kimmel lived for a number of years in the Georgetown section of Washington, D. C., where he entertained many of his literary friends, as well as such notables as the Duke of Windsor, Great Britain’s former King Edward the Eighth. It was also on his way to Washington in 1934 that Kimmel first visited Tudor Hall in Maryland and became interested in the family of John Wilkes Booth. Two years of intense research led to his writing a series of articles on the Booths for the Washington Star, and after four additional years of digging deeper into Booth history, Kimmel finally saw his definitive work on the family, The Mad Booths of Maryland, published in 1940. The book immediately made the best-seller lists nationwide, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and the massive file of his research notes displayed in the Library of Congress. The author’s interest in events during the Nineteenth Century continued, however, and in 1957 and 1958 his twin volumes on the two wartime capitals, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington and Mr. Davis‘ Richmond, were published. The two books each contained a highly accurate and extremely even-handed description of the events and protagonists in both cities during the War Between the States, as well as a massive number of rare photographs from that period. At the time of their publication over half a century ago, while neither book attained the status of Kimmel’s previous study of the Booths, they were each widely acclaimed by both the general public and wartime historians.

What makes Kimmel’s three books about Nineteenth Century America so relevant now is the simple fact that the author never allowed himself to become bogged down with the heavy baggage of political correctness. Kimmel always approached his subjects with an eye to contemporary history, and in the context of the period in which such events actually took place, rather than attempting to fit them into present-day mores. Furthermore, he always tried to describe the events on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line as they might have been witnessed by the people of that period, not as people currently prefer to view them. On Kimmel’s literary stage there appeared many true heroes dressed in both Confederate gray and Union blue, each proudly waving on high their nation’s banners . . . would that the theater of today allowed such balanced performances.