Sound was the first victim of the attack on southern heritage. In October 1971, the University of Georgia’s “Dixie Redcoat Marching Band” dropped the word “Dixie” from its name and discontinued playing the song “Dixie” after the National Anthem. Many people, even to this day, will argue that “Dixie” was played and perpetuated to uphold white supremacy. But the tradition goes much further back in college football history, specifically to when the University of Alabama defeated the University of Washington in the 1926 Rose Bowl. The Atlanta Georgian labeled the 1926 Rose Bowl victory as “the greatest victory for the South since the first battle of Bull Run.” The Atlanta Journal argued the football team belonged in the pantheon of Confederate leaders Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson: “The Crimson Tide no longer belongs exclusively to Tuscaloosa and the state of Alabama. It belongs to the whole South just like the Stone Mountain Memorial.” In addition, after the Alabama Crimson Tide returned to the Rose Bowl in 1927, the marching band performed the song “Dixie” as the players stormed the field.

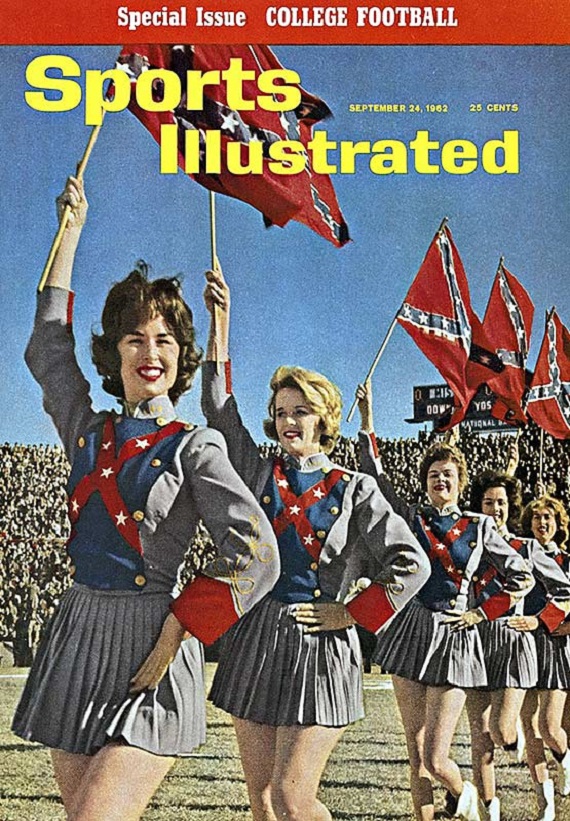

In a 1941 game against Yale, College Topics reported “a thousand hands” lifted the Confederate battle flag and fans from both teams sang “Dixie” at halftime to mark the first documented example of Confederate recognition at a Virginia football game. The situation was best exemplified when “Dixie” was played in 1947 after an African-American tackle from Harvard, Chester Pierce, broke the southern color line in a home game at Charlottesville. Many accounts show that Pierce received applause upon leaving, and he even stated: “I don’t recall a hint of anything racial on the field. I remember nothing different in that game from any other I played at Harvard … It was no big deal and took no courage by me.” In 1997, the University of Virginia awarded Pierce its Vivian Pinn Distinguished Lecturer’s Award. It is given for lifetime achievement in the field of health disparities. Pierce was also invited back to Charlottesville in 2007 to speak at Virginia’s second annual Symposium on Race and Society. Also in 1962, the Florida Gators wore Confederate flags on their helmets and entered the stadium to the tune of “Dixie” as they defeated the favorite, Penn State, in a win at the Gator Bowl. Simply put, Confederate symbols and sounds were a part of southern college football.

“Dixie” was played at football games, along with people waving Confederate flags, for decades without incident. Once the University of Georgia purged its history of “Dixie,” many other Universities began doing the same to bow to the pressures of political correctness. While most of these institutions did so in the name of inclusiveness and diversity, they were really done for political expediency. Just as modern politicians look to make names for themselves by assaulting Confederate heritage, so too do these Universities and coaches. In 2015, after the Emmanuel Church shooting, Steve Spurrier tweeted on June 23rd: “The South Carolina football team, players and coaches strongly support Governor Haley’s decision to remove the flag from the capitol.” He then resigned that October after several mediocre seasons.

This obsession with sports and how they intersect with our daily lives is solid proof of national decline. Before the fall of Rome, for example, chariot races and gladiator games became a central part of society. The most famous charioteer of the time was named Gaius Appuleius Diocles, who amassed a fortune of 35,863,120 sesterces – the equivalent of $15 billion today — while many Romans were still of the Plebeian class and depended on the government for food. Similarly, our modern athletes are paid fortunes for minutes of playtime. When you break down how much they actually compete compared to how much they are paid, many athletes earn more than the average person’s yearly salary in one quarter of a sports game, while the US Census Bureau showed in 2016 that there were 40.6 million people living in poverty. Professional sports are simply a distraction to keep us from discussing real issues and problems within society, and we can clearly see that we have more sports now than ever.

Don’t just take my word on this, the athletes themselves are using their platform to bash America. To allow the waving of Confederate flags and for marching bands to continue playing the southern sound of “Dixie” in such a time would be like openly welcoming the disintegration of America. Part of the reason for this contention is that “Dixie” in itself is a very “American” sounding anthem. Lincoln himself stated: “I have always thought `Dixie’ one of the best tunes I have ever heard. Our adversaries over the way attempted to appropriate it, but I insisted yesterday that we fairly captured it. I presented the question to the Attorney General, and he gave it as his legal opinion that it is our lawful prize.” It was almost as if Lincoln wanted to take the song and remake it in his image, which eerily reminds us of the assault on Confederate heritage today.

But the assault on “Dixie” did not end with sports. In 1990, the state of Texas asked the Texas State Fair to discontinue playing Elvis Presley’s “American Trilogy” because of it’s “Dixie” content. Elvis was a man that always tried to appeal to all Americans, black and white. His songs like “If I Can Dream,” “In the Ghetto,” and “America the Beautiful” all looked to provide hope. Presley’s “American Trilogy” took distinct cultures in America and blended them for a patriotic and meaningful experience. The trilogy consisted of “All My Trials” an African American spiritual set to a Bahama lullaby, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to honor the Union, and “Dixie” to honor his southern homeland.

Sources show that Elvis had several Confederate ancestors: one fought for South Carolina and another married into John Bell Hood’s family. A direct ancestor named Darlin Presley of North Carolina, fought in Pickett’s charge, and was later captured and died at Point Lookout Prison Camp in Maryland. Finally, Elvis’s great-great grandfather is thought to be Duane Presley, Jr., who twice joined and deserted two Confederate regiments in Mississippi.

Charles Reagan Wilson wrote in Judgment and Faith in Dixie (1997) that Elvis’s “slow, reflective, melancholy” performances of the song in the 1970s “suggested an emotional awareness of the complex past of regional conflict and Southern trauma.” With no concrete evidence of “Dixie” being used as a tool of white supremacy, it seems odd that by 1990, people were making a push to remove the anthem completely from the public arena. In 1934, the music journal The Etude declared that “the sectional sentiment attached to Dixie has been long forgotten; and today it is heard everywhere–North, East, South, and West.”

The people who sing “Dixie” and wave the Confederate flag are the same people that stand during the National Anthem and win America’s wars. Even though “Dixie” might have been removed from the public arena, it will always live on in the hearts and minds of all true southerners. There’s no reason for us to stress, because we are in the process of writing a new song for the south.