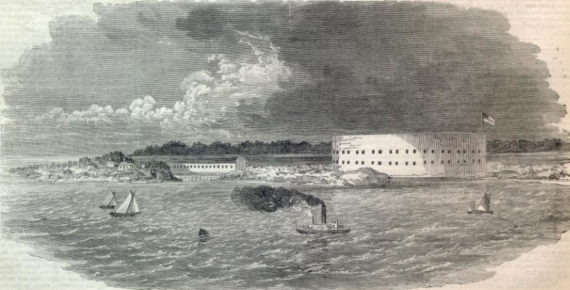

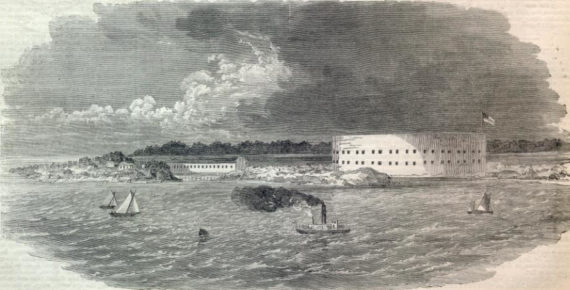

When the Pacific phase of World War Two began in December of 1941, Great Britain’s main bastion of power in Southeast Asia was its eighty-five thousand man army behind the fortifications at Singapore, the so-called Gibraltar of the Pacific. The problem was, however, that all the island’s massive protective firepower faced the Straits of Singapore rather than the Malay Peninsula through which General Yamashita’s thirty-six thousand Japanese troops were rapidly advancing toward the island fortress. Within a week, the Japanese Army poured through Singapore’s unprotected rear and captured or killed the entire garrison. Eight decades prior to that, a similar scene was being enacted at Charleston, South Carolina, just before that State’s secession from the Union on December 20, 1860. In that instance, the guns of the only fortification occupied in any strength by Federal troops, Fort Moultrie, were facing Charleston Harbor rather than the city. To compound the tactical problem, a row of private homes had been built within a stones throw of the open rear of the aging fort and anyone or anything, including livestock, were able to gain easy entry into the facility. The garrison’s commanding officer, Major Robert Anderson, of course realized that his position was indefensible and that he and his seventy-five troops would soon have to move to the unfinished and unoccupied, but far more defendable, Fort Sumter in the middle of the harbor. There was, however, one obstacle to such an action . . . one that was political rather than military.

During this period of extreme sectional unrest and amid the darkening clouds of war, negotiations had been conducted in Washington on December tenth between the six South Carolina congressmen and President Buchanan regarding the military situation in Charleston. While no written agreement had been made on the matter, the president did offer a verbal pledge that if South Carolina did not attack the forts, the Federal government would maintain the status quo there, and Buchanan included his promise that no reinforcements would be sent to the area and that the State would be immediately informed of any change in policy. Thus was formed a de facto truce which the South Carolina delegation had regarded as a binding gentlemen’s agreement that also meant that Major Anderson would not be ordered to move his garrison to Fort Sumter. On the other hand, while President Buchanan did not consider the rather ambiguous agreement to be in any way binding, he did for the time being give up his plans to reinforce Anderson. However, in spite of this tacit agreement, the following day a War Department representative, Major, and later major general, Don Carlos Buell met with Anderson in Charleston and informed him that should the situation call for it, he had official permission to remove his command to Fort Sumter.

When South Carolina seceded later that month and after Anderson had made his move to Fort Sumter, General Winfield Scott, the Union’s commanding officer, ordered a secret plan be prepared to immediately reinforce the fort by means of an unarmed passenger steamship, the “Star of the West.” The ship was to be loaded with troops, munitions and supplies and make an unscheduled port stop in Charleston as part of its normal route between New York and New Orleans. As always in Washington, the covert action was leaked, this time by outgoing Interior Secretary Jacob Thompson of North Carolina, with news of the reinforcements soon making its way to Charleston. When the “Star of the West” attempted to enter Charleston Harbor on January ninth, the cadets from the Citadel Military Academy stationed at the battery on Morris Island fired a shot across her bow and the ship sailed back to New York. History has termed that single shot to be technically the South’s first actual hostile act of the coming war, but that honor really belongs to the North, for the first authentic shot was not from a Southern gun at Charleston, but from those fired by Federal troops six hundred miles to the South. Neither was the North’s secret attempts to reinforce a Federal fort in the South prior to hostilities relegated to only South Carolina.

The day before the “Star of the West’s mission was turned back, and two days prior to Florida’s secession on January tenth, a group of Florida militiamen led by Colonel William Chase arrived at Fort Barrancas in Pensacola and requested the fort’s surrender. The facility was being held by fifty Federal troops under the command of Major John Winder, later a Confederate brigadier general and the commander of Libby Prison in Richmond. Major Winder, however, was absent at the time and the acting commander, Lieutenant Adam Slemmer, ordered that warning shots be fired to force the Southern intruders to retire. Lieutenant Slemmer, like Major Anderson, also felt his position on the mainland, as well as that at nearby Fort McRee and the Pensacola Navy Yard, would be difficult to defend in the event of a full-scale attack, and the next night he moved his troops and thirty sailors from the Navy Yard to the stronger, and then unoccupied, Fort Pickens on Santa Rosa Island in Pensacola Bay. On January fifteenth, Colonel Chase went to Fort Pickens, a facility he had helped design and build while a captain in the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, and made an unsuccessful demand for the fort’s surrender. A few days later, General Scott gave confidential orders that a contingent of Regular Army troops under the command of Captain Israel Vogdes of the First Artillery Regiment, a former professor of mathematics at West Point, be sent to Fort Pickens aboard the twenty-one gun sloop of war “U. S. S. Brooklyn.”

This order too was quickly learned of by those in the South and on January twenty-ninth, Senator Stephen Mallory of Florida, who would soon be named the Confederate secretary of the Navy, met with President Buchanan to try and prevent the action. The president informed Senator Mallory that the warship would proceed to Pensacola as ordered but pledged that unless Fort Picken was actually attacked, the troops would not be landed. This promise was kept, and the troops remained aboard the ship until Lincoln took office on March fourth, but on March twelfth, a month prior to the firing on Fort Sumter, further secret orders were sent to Captain Vogdes by General Scott and Navy Secretary Gideon Wells that his troops were to be immediately put ashore. Not trusting the security of the telegraph, these new orders were carried by Navy Lieutenant John Worden by rail and then by sea aboard the “U. S. S. Crusader” and were not delivered to Vogdes until March thirty-first. However, when Worden relayed the order to land Vogdes’ troops to Navy Captain Henry Adams aboard the “U. S. S. Sabine” the following day, Adams said he considered the landing to be an act of war and refused to carry out the order.

Meanwhile two other vessels loaded with both Army troops and Marines had also been put to sea from New York prior to the start of the War to reinforce Forts Pickens and Sumter . . . with the chartered steamship “Baltic” under the command of Navy Lieutenant Gustavus Fox heading for Charleston and and the warship “U. S. S. Powhatan” being sailed to Pensacola by Navy Lieutenant David Porter, as well as Commander Stephen Rowen also being sent to Charleston from Hampton Roads in Virginia with additional troops aboard the “U. S. S.. Pawnee” and the Revenue Cutter “Harriet Lane.” After the firing on Fort Sumter and the start of the War on April twelfth, while the troops sent to Charleston could not be landed because of the hostilities, those at Fort Pickens were all landed, the first being the ones led by Captain Vogdes on the night of the eleventh, a few hours before the actual firing on Fort Sumter, and the remainder on April sixteenth and seventeenth under the Command of Colonel Harvey Brown and Captain Montgomery Meigs. The “Powhatan” also arrived at the scene late on the seventeen flying the British flag in an attempt to mislead the Confederate shore batteries. Even though attacked by Confederate forces six months later during the Battle of Santa Rosa Island, the first major land battle to occur in Florida, Fort Pickens remained in Union hands until the end of the War under the command of Colonel Brown.

The Battle of Santa itself had been instigated by a Union Navy raid on September fourteenth that year which destroyed the Confederate privateer “Judah” that was docked at the former Pensacola Navy Yard. In retaliation the next month, the commander of the Confederate forces in that area, Brigadier General Braxton Bragg, ordered Brigadier General Richard Anderson to land over a thousand troops on Santa Rosa Island in an effort to capture Fort Pickens. The force was composed of elements from the First and Seventh Alabama Infantry, the First Florida Infantry, the Fifth Georgia Infantry and the First Louisiana Regiment. Their initial attack was made on a battalion of Union Zouaves that was camped on the beach about a mile from the Fort, the Sixth New York Volunteers under the command of Colonel William Wilson. After the opening Confederate volley, the former New York firemen panicked and fled to the Fort in wild disorder. Seeing this, Colonel Brown ordered Vogdes, by then a major, and about a hundred men to cover Wilson’s retreat, but when they were attacked by Company “B” of the Fifth Georgia under the command of Captain Samuel Mangham, the “Griffin Light Guards,” and Vogdes captured, a larger group of infantry and an artillery battery were then sent from the Fort under Major Lewis Arnold and they finally managed to drive Anderson’s forces off the island . . . with about a hundred casualties on either side.

As a footnote to these events, while visiting Fort Adams in Rhode Island during 1881, one of the veterans from Company “B” of the Fifth Georgia Regiment who had been a fifteen year old drummer boy at the Battle of Santa Rosa, Huger W. Johnstone from Idylwild, Georgia, happened to meet Israel Vogdes who was then a brigadier general and had only recently retired from the Army. While the two were reminiscing about the attack on Fort Pickens, the general told Johnstone that after his capture he had been one of the thirteen Union officers sentenced to be hanged in reprisal if the crew members of the Confederate privateer “Savannah” which had been captured near Charleston that June were executed for piracy in New York. He said that fortunately for all concerned, the charges against Captain Thomas Baker and his twelve sailors were dropped and that a year later both he and the Confederates had been exchanged. Vogdes also spoke of President Lincoln’s actions prior to the start of the War and admitted that he now agreed with Navy Captain Adams that the original order in March of 1861 to land his troops on Santa Rosa Island would indeed have been an act of war. As they parted, General Vogdes added that he had only later learned that his landing to reinforce Fort Pickens actually took place several hours before the bombardment of Fort Sumter had commenced. While Vogdes did not actually say so, it should certainly be obvious that his admission also provides added evidence to the charge that Lincoln’s strategy had been to force the South into firing the first shot in Charleston Harbor, a move designed to allow the North, and of course history, to lay the onus for the War at the doorstep of the Confederacy. . . . . . ergo, denset erant autem insidiamini!