When most Americans hear the word slavery today, their minds instantly conjure up only images of either a black African in chains or a group of such people toiling away in the fields of some Southern plantation. This distorted, even psychotic, mental picture of an institution that is as old as civilization itself is now, of course, being used not only as both a means of erasing from history any object or individual that might have been in any way connected with its practice and a divisive propaganda tool to further the aims of certain political campaigns, but also an attempt to gain unwarranted monetary compensation for any descendent of such a Southern slave. As it does not fit into either the current political agenda or politically-correct mantra, virtually no attention is ever given the black slavery that existed in the American colonies and states above the Mason-Dixon Line for more than two centuries. Neither is any serious thought usually given to the origins and rationale of slavery that began over six thousand years ago or its existence in every civilized society throughout the world until the late Nineteenth Century and a practice that even continues today, with upwards of fifty million people in some form of bondage in parts of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, including those held by the so-called Islamic State “Caliphate” in the Middle East and its barbaric offshoot in Nigeria, Boko Haram.

While some forms of slavery probably existed at least ten thousand years ago, its actual practice as a recorded institution began about 4000 BCE in the Sumerian kingdom located within the “Cradle of Civilization,” the fertile crescent of land that lies between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers known as Mesopotamia which is now the nation of Iraq. The first written laws pertaining to slavery appeared two millennia later in the Code of Hammurabi, the sixth king of Babylon. That section of his Code even contained a clause relating to the return of escaped slaves and demanded the death penalty for anyone who stole a slave and carried such person beyond the borders of Babylon . . . sort of a forerunner to the United States’ Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Slavery continued to expand into the Egyptian, Assyrian and Persian empires, and then spread around the entire Mediterranean area to the ancient empires of Carthage, Greece, Macedonia and Rome, as well as throughout Africa, Asia, Oceania, the pre-Columbian Americas, Europe during the Middle Ages and the later Turkish Ottoman Empire that existed until the end of World War One.

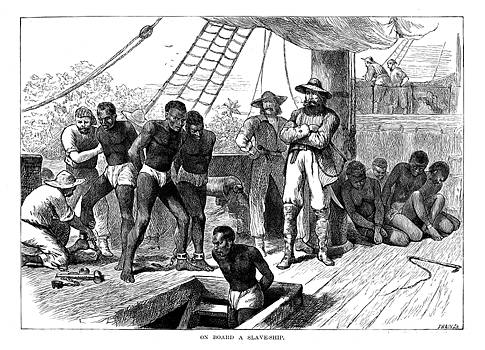

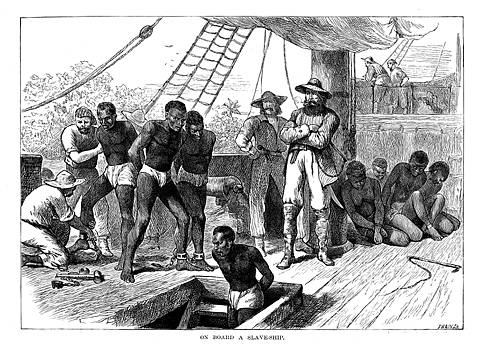

While the slaves in those earlier civilizations were mainly men and women of all nationalities captured in conquered lands, those enslaved from the early Seventeenth Century on by the more modern nations of England, France, Holland, Portugal and Spain were mainly Africans purchased from Arab slave traders who had previously bought them from some other Africans. Attempts had also been made by such nations to enslave other ethnic groups from their colonial empires in Asia and South, Central and North America, but most such native people proved to be unsuitable as slave laborers. By the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, while serfdom continued in much of eastern Europe, actual slavery and the slave trade itself had ended in the western European nations. In the United States, most slavery in the North was banned on a state-by-state basis during the early part of the Nineteenth Century, with the last vestiges coming to an end in New Jersey and the southernmost counties of Illinois, the area known as “Egypt,” by the close of the War Between the States. Even so, it is estimated that as late as 1800 approximately two hundred forty million people, three-quarters of the world’s population at that time, were still held in some form of bondage or serfdom, with the last nation in the Americas to enact a legal cession of slavery being Brazil in 1888 and last nation to do so worldwide the Islamic Republic of Mauritania in Africa almost a century later.

One must also not fail to include the countless generations of people who have had to work under slave-like conditions in countries throughout the world, including the United States during its earlier history. Nor should they forget the many millions of slave laborers used by the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany and similar totalitarian nations prior to, during and after World War Two . . . all of whom lived and worked under the most horrible conditions imaginable, with many either falling dead while performing such labors or being exterminated by their masters when they were no longer able to work. With all of this in mind, it should certainly be evident to any thoughtful individual that slavery is not merely a simple black and white issue which is unique to America in general and the South in particular, but a problem that has had an extremely long and complex history which has, during one era or another, brutally touched every nation on earth in some manner. Sadly this is not the case, as such facts do not fit well into the current agendas and run counter to today’s dictates of political correctness. The basic myth that the noble North only went to war to end the curse of slavery, while those in the South rose up en masse to defend the evil institution has been repeated so often by so many historians, the media and self-serving politicians that it has now become accepted in toto by a majority of the public. Even the secondary myth that Lincoln’s proclamation of 1862 freed all of the slaves in America with the sweep of a pen has become historic dogma. This is in spite of the fact that a simple reading of the so-called emancipation document would reveal that Lincoln’s hundred-day order did not apply to any of the slave states still in the Union, namely Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland and Missouri. Moreover, the proclamation specifically excluded both the areas of Louisiana and Virginia then under control of the Union Army, as well as all the Virginia counties that would later become the unconstitutionally-created State of West Virginia. In Lincoln’s own words, all the areas he so delineated were to be “left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.”

All of which unfortunately goes to prove as correct the old adage that if any lie, no matter how massive it might be or what gross misinformation it might contain, is told long enough to a sufficient number of people . . . it will one day be accepted as factual by everyone.