The 1970’s were an interesting time in the South. The 1970’s were the last time Southerners could be Southern without feeling the need to apologize for, or be ironic about, their Southern identity. In fact, in the 1970’s, it seemed to actually go a little beyond this. We shouldn’t push this too far, but in 1970’s America there seemed to be an acceptance of the South as a cultural asset to American life, something that added value to that classic 70’s notion of the ‘Great American Melting Pot.’ In America in the 1970’s, being Southern could be a good thing. It could even been cool to be Southern.

It’s not entirely clear when and why this happened, although it seems to have essentially come to an end by the time of Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in 1981. It’s remarkable, though, that it happened at all. What most defined the South in the minds of non-Southerners during the 1960’s was the Civil Rights movement; those indelible images of burned-out buses, Bull Conner, Birmingham, Selma and so forth. These images shocked Americans outside the South, but also did something else. During the early 60’s at least, it allowed those Americans to rest comfortably in the idea that racial tension and social unrest, while terrible to look at, was at least something confined to the South, that troublesome, benighted region, that odd place always out of step with the real America in which everyone else lived. This was a Southern problem because the South was itself a problem. It had always been a problem. It was an echo of Robert Penn Warren’s old ‘treasury of virtue.’

And then something happened. That comfortable bubble of virtue popped. Kennedy was assassinated. The conspiracy theories started. All of a sudden something didn’t seem quite right in America, never mind the South. Meanwhile, Lyndon Johnson, a Southerner from Texas, pushed through the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act which seemed to win for the Civil Rights movement all it had aimed for. That movement turned its focus elsewhere, like the big cities of the North. Martin Luther King, Jr. said that he never encountered the same level of hostility in the South that he did in Chicago. There was the Vietnam War, the antiwar movement and the growing counterculture which looked askance at what it considered an arrogant and conformist American society, one which, maybe not so ironically, had looked down its nose at those backwards Southerners just a few years before. By 1968 the country was at a boiling point. King was assassinated by a petty criminal from Illinois. More conspiracy theories followed. Riots erupted in Detroit, Los Angeles and Washington. The Democratic convention in Chicago was a disaster for the party. RFK was assassinated in California. There were still more conspiracy theories. There was Tet, Nixon, Woodstock, the Summer of Love, Linebackers I & II, and finally Watergate. By the beginning of the 70’s, Americans might be forgiven for having thought that not all of their problems were confined to the South.

Perhaps what seemed now like an easing of racial tensions in the South, especially with the new awareness that social conflict was an American phenomenon, not just a Southern one, led to an openness to rethink what the South meant to America? If Southern history was a tragic history, then at the beginning of the 1970’s it seemed like all of America had passed through a tragic era. While something might have been gained, it felt like something had been lost too.

Or maybe this new found sympathy for the South came from hearing Senator Sam Ervin’s wonderful old North Carolina accent during the Watergate hearings in 1973? Ervin seemed like a voice of wisdom and integrity from the days of the Old Republic against the organization men of the Nixon administration. Or maybe it was going to the movies in 1973 and watching Joe Don Baker portray a Tennessee Sheriff named Bufford Pusser, walking tall, carrying a big stick, and taking on a different kind of corruption in McNairy County?

Positive depictions of the South and Southerners could be found all over the place in movies and on television in the 1970’s. Just watch Clint Eastwood in The Outlaw Jose Wales (1976), or Burt Reynolds in Smokey and the Bandit (1977), or even John Travolta in Urban Cowboy (1980). There was the Waltons, set in Depression era Virginia, (1972-1981) the most popular show on television and, of course, there was The Dukes of Hazzard (1979-1985). Burt Reynolds was the epitome of cool in the 70’s. Watch White Lighting (1973) and Gator (1976). Burt Reynolds proudly identified as and was recognized by everyone else as a Southerner. Network television even still occasionally showed Gone with the Wind and Disney’s Song of the South, all without feeling the need for a disclaimer or a content warning.

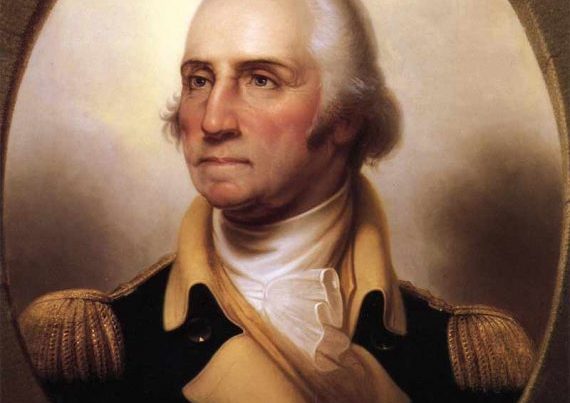

1976 seems to have been a watershed for the South’s place in American life during the decade. It was, of course, the Bicentennial year. This sparked a renewed interest in the Revolutionary Era and the Founding Fathers, reminding Americans that many of the most critically important Founders were, after all, Southerners. You don’t have a Bicentennial without the South, and we should recall how unabashedly celebratory was the tone of the Bicentennial. The South was an integral part of this glorious moment in American history and of its two hundredth anniversary as well.

And of course, there was the election of Jimmy Carter in 1976. People sometimes think of Carter’s election as a fluke, coming after Watergate and the Nixon pardon, the taint of which Ford just couldn’t shake. Certainly, there’s some truth in that, but it’s worth noting that when pollsters asked Americans, in the Bicentennial year of 1976, what they most wanted in their next president it was honesty, integrity and decency. And who they chose was a previously unknown governor from Georgia over not just Gerald Ford of Michigan but several more prominent candidates for the Democratic nomination. Carter clearly benefit from a national perception of the South and Southerners as being more authentic, ‘real’ and ‘down to Earth.’

Think about 1976. The election that year was razor thin, but remarkably placid and dignified when compared to more recent contests. This was a political world very different from ours, although it really wasn’t all that long ago. It was a far less partisan, less ideological time. This was a time before most Americans had cable television, before the internet, when making a long distance phone call was expensive and people didn’t do it much. People still wrote letters, by hand, to each other in 1976. All of these technologies we have today which were supposed bring us together, to make communication easier, make ideas flow more freely, certainly did some of that, but they also seem to have made us, ironically, more isolated, more distrustful, less willing to speak freely, more angry, and more rigidly ideological.

The South could also be heard very clearly on the radio, the turntable and the 8-track in the 1970’s. By the 1970’s country music had become mainstream American music. Its influence was everywhere in the culture in the 70’s. This was the era of Outlaw Country; Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings and when Austin City Limits seemed to have nothing but country artists on its show. Even in Rock music you could hear lots country influences. Just take a listen to the Eagles. This was a time when genre boundaries were not quite as rigid as they later became, and mainstream artists felt free to explore different influences. In fact, one could argue that the 1970’s was the most creative period in the history of post-World War II American popular music. An important part of all of this creativity was Southern Rock. The earliest Rock pioneers had been Southerners making Southern music, but for various reasons, by the early 1970’s, the connection between Rock music’ origins and the South had been forgotten. Whatever Rock was, it wasn’t Southern.

Then The Allman Brothers kicked the door open for Southern Rock musicians and bands identified with the South and the Southern Rock Movement. As a presidential candidate, Jimmy Carter embraced the movement and the movement embraced him. Southern Rockers, Lynyrd Skynyrd among them, played fund-raising concerts for Carter. The Marshall Tucker Band even played at Carters’ inauguration party, and Carter picked Charlie Daniel’s “The South’s Gonna Do it Again” as his campaign song. To get a sense of what this all meant read the first paragraph of an article from The New York Times published on July 24, 1977. It was written by respected music writer Robert Palmer. Admittedly, the cultural moment Palmer describes didn’t last very long, but it was real, and it’s been largely forgotten.

“Confederate flags waved in Central Park last summer when the Marshall Tucker Band performed, and longhaired fans in overalls square danced. The Atlanta Rhythm Section, opening shows for Alice Cooper on his current tour, has been greeted by rebel yells in the most unlikely places. Clearly, Southern rock has a mystique all it’s own, one which transcends regional differences. In part, this is because white Southerners still seem exotic, and therefore fascinating, to many Americans-‐a Southern friend was recently asked in New York whether his people had really wanted to secede-‐and because our Southern president has popularized Southern chic. But the Southern rock band predated and perhaps helped create the climate for Jimmy Carter, and exotic or not, the music is distinctive enough to have created a nationwide audience strictly on its own merits.”

Confederate flags waving in Central Park! The South is chic! Southerners are exotic and interesting! Southern Rock music blazed the path for Jimmy Carter! These are fascinating images and notions, and they are important because Rock music mattered in the 1970’s. As it was later in the 1980’s and 1990’s, but perhaps less so today, young Americans defined themselves by the music they listened to. This was powerful stuff. For young Southerners, Southern Rock was a way to affirm and express their Southern identity in this new, confusing and crazy world of the 1970’s. And it was fun, upbeat and positive. It felt good to be Southern. The South was hip, culturally relevant and cool.

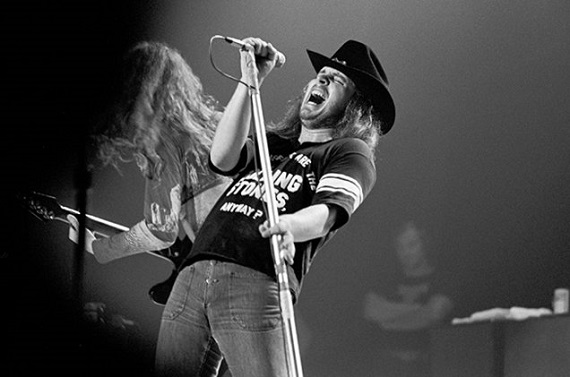

While the Allman Brothers Band was certainly important, the band that perhaps most represents the Southern Rock moment of the 1970’s is Jacksonville, Florida’s Lynyrd Skynyrd. To appreciate Skynyrd, you have to understand Ronnie Van Zant. If Southern Rock had a representative figure, the one person who most embodied the ethos of 70’s Southern Rock, it was Skynyrd’s lyricist and lead singer. Ronnie Van Zant was the heart, the soul and driving force of Lynyrd Skynyrd. He’s now a Rock icon, and I think we can add Southern icon to that too. Ronnie Van Zant is also one of the most unappreciated lyricists in Rock history. In his Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame induction speech for Skynyrd in 2006, Robert James Ritchie, a.k.a. Kid Rock, said that Ronnie Van Zant was a Southern poet. Kid Rock is right. Ronnie was a genuinely significant 20th century Southern voice who is due a proper recognition.

That it hasn’t been fully granted may be because the image of Ronnie and the band he led has loomed so large, and for so long, it has hid his songwriting. It won’t come as a revelation to anyone that the music scene of the 1970’s embodied the now well-worn phrase of “sex, drugs and rock and roll.” All you can say is, “It was the 70’s,” and that was the lifestyle for a large number of Rock musicians and fans. Hedonism, recklessness and self-indulgence defined the era, and it wasn’t just at Studio 54. It was everywhere. Lynyrd Skynyrd had a reputation, however, for not just keeping up with the Joneses, but of setting a standard for others to follow. There were hotel rooms trashed, T.V.s thrown out of windows, drunken rampages, drug use and lots of fights.

Part of that image is Ronnie Van Zant as a mean, tough, Florida redneck who liked to drink and fight with equal gusto. Well, there is as much truth as myth here. It’s not the whole story, but it is a part. Early in Skynyrd’s rise, manager Allan Walden took the band to New York to do some interviews. Asked by one journalist if it was true what he had heard, that he and the Skynyrd boys were just a bunch of rednecks, Ronnie looked him in the eye, sneered, and said, “Hell Yea. Damn right. Where’s your daughter?” Was this playing to type, or a straightforward and honest declaration? Maybe a little of both? Ronnie Van Zant was a very savvy guy.

Ronald Wayne Van Zant was born in 1948 and grew up in the Westside area of Jacksonville in a modest house at the corner of Mull Street and Woodcrest Road. It’s now a Florida State Historic Site, compete with a sign. His father Lacy was a long haul trucker working the East Coast and his mother Marion Virginia “Sister” Hicks worked in a donut shop at the time he was born. She would have an enormous influence in shaping his character since his father was often on the road. At the time, the Westside was a large, sprawling, semi-rural, blue-collar neighborhood that was more or less the transition zone from rural North Florida to downtown Jacksonville. Many there worked for the railroad or the port in Jacksonville. Some of the roads were paved. Others were dirt. In 1968 Jacksonville and Duval County consolidated making Jacksonville the largest city in the world by land area. The Jacksonville and Northeast Florida that Ronnie grew up in was still culturally very Southern. It was often called ‘South Georgia south.’

Fully grown, Ronnie would stand a stocky 5’7, and his own mother recognized that he was one of the toughest boys around. Ronnie liked to fight, especially when a point of personal honor was at stake, but sometimes because, well, because it was fun. Lots of other Westside boys like to fight too. Ronnie won his share, but apparently didn’t win every time either. Ronnie wasn’t just a fighter though. He is remembered by an early girlfriend as sweet, romantic and gentlemanly, a kind of dirt road knight errant; a fighter and a lover. More than fighting, Ronnie loved the outdoors. He and his childhood friend Gene Odom would go fishing in nearby Cedar Creek and other local fishing holes. Gene claims that Ronnie loved fishing even more than music. They would sometimes catch huge sacks of mullet from the creek and give them all away to various people in the neighborhood. If not fishing, the two would go squirrel hunting or just wander the woods which were thick in the surrounding area.

There was also the nearby Speedway Park, famed as the fasted half-mile dirt track in the U.S. and once part of the NASCAR circuit. Ronnie and Gene would climb trees tall enough for them to watch for free. Richard Petty, Junior Johnson, Fireball Roberts, the Allison brothers, and Wendell Scott all raced there. In fact, Lee Roy Yarbrough, winner of the 1969 Daytona 500, lived in the Westside neighborhood and Ronnie and Gene would spend hours hanging out with him as he worked on his cars. Ronnie did some drag-racing himself and once owned a red 1965 Ford Mustang with the 289 cubic inch engine with the three speed stick shift. He considered being a professional racer car driver for a while but crashing the Mustang put an end to it. He later worked at an auto parts store where he knew every part and its location by memory.

Ronnie was a good baseball player too, enough to have aspirations of being a professional, and since he was good with his fists, he thought about boxing too. Ronnie loved Muhamad Ali but came to like Ali’s words more than his punches, his ‘fly like a butterfly, sting like a bee’ style of pithy poetry. Ronnie was a budding poet of sorts himself, secretly, and quietly, keeping a little journal under his bed with jokes, sayings, stories, and strands of lyrics. He attended Robert E. Lee High School, and did well enough, but dropped out his senior year. By then Ronnie had already decided what he wanted to do.

The world in which Ronnie Van Zant grew up certainly wasn’t the Old South. It was a New South, but one still connected to old rural ways. He and his companions in Jacksonville’s Westside were just a generation or two removed from the farms and fields. These were the same sort of people who, if this had been the Southern Piedmont instead of North Florida, would have been working in the cotton mills. Instead, they worked for the railroad, at the port, joined the navy or the army, or drove stock cars. Ronnie’s father Lacy was a teller of tall tales, and clearly that love of storytelling rubbed off on Ronnie. Lacy also loved old time country music, and from an early age Ronnie loved it too. One of his favorites was Merle Haggard, but he was saturated in the stuff and would have heard all the great country crooners of the 50’s and 60’s. These influences would be essential for Ronnie. (Ed King would later say that Lynyrd Skynyrd was a rock band fronted by a great country singer.)

Like everyone else, Ronnie listened to the popular music of the early and mid-60’s, but he had a special fondness for the offbeat stuff like Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs who had hits with “Wooly Bully” and “Little Red Riding Hood.” He also liked the Beach Boys when they came out, interesting since Ronnie and Skynyrd sound nothing like the Beach Boys.

In 1965, at the age of seventeen, Ronnie and friend Bill Ferris saw The Rolling Stones perform live in Jacksonville. This was at the peak of Beatlemania, and the Stones weren’t yet a top draw. But the experience made an impression on Ronnie. Skynyrd would sound more like the Stones than the Beatles. Ronnie was a lifelong Stones fan, as all the guys in Skynyrd would be. In 1976 the Stones headlined a massive concert in Knebworth Park in Hertfordshire, England. Several bands were on offer, among them Skynyrd who by all accounts put on a better performance than the headliners.

By his senior year of High School, Ronnie had already decided he wanted to pursue music, and he pursued it with a steady determination. He was soon joined by some other Westside boys; guitarists Allen Collins and Gary Rossington and Bob Burns on drums all of whom had played in local high school bands. Together they began to play local shows throughout Jacksonville at places like the Comic Book Club, a local teen hangout. From the beginning, Ronnie was the leader, and it wasn’t just his singing, or the lyrics. Ronnie would beat you up if you were late for practice, if you weren’t giving 100% during a show, if you missed a fill or screwed up a solo. That was Ronnie’s drive to succeed. Without a doubt, you would have never heard of Lynyrd Skynyrd if Ronnie hadn’t driven his bandmates like stubborn mules plowing a spring field. They started as the Noble Five with Larry Junstrom on bass, then they were the Pretty Ones, and then the One Percent.

One of the first songs Ronnie ever wrote, in the late 60’s, was an anti-Vietnam war song he titled “Chair with a Broken Arm.” Having long hair and playing in band in North Florida in the late 60’s could be a little dangerous. At a show in Perry, Florida, these long-haired, redneck rockers from the Westside of Jacksonville ran into some old school, crew-cut rednecks who probably thought they were hippies and took after them. Nonetheless, they escaped to play another day.

The One Percent played a lot of covers; CCR, Cream, Rolling Stones, even some early Zeppelin. Playing constantly, but unsatisfied with their name they sought a new one. Gary and Bob Burns, were constantly in fear of R. E. Lee High School gym coach and dress code enforcer (and later real estate agent) Leonard Skinner. In constant fear of getting busted for their long hair and smoking, they joked about Leonard Skinner always harassing them. And then the joke became the name. That’s the origin of the name ‘Lynyrd Skynyrd.’

Soon afterward, the newly named Skynyrd got big time attention. In 1969 Greenville, SC native and Mercer University graduate Phil Walden founded Capricorn Records in Macon, Georgia to be the record label for the Allman Brothers Band. Walden had managed R&B giants such as Al Green and Percy Sledge and Duane Allman, originally from Daytona Beach, tipped Phil and his brother Allan off to all of the musical talent in Florida, particularly the Jacksonville area.

In 1970 Allan Walden came to Jacksonville for a local band showcase in an old warehouse. Skynyrd was there and was the best of the bunch. He soon had them doing recordings at the legendary FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama and tried to get his brother Phil to pick them up on Capricorn. But, Phil rejected them as sounding too much like the Allmans.

Skynyrd’s Muscle Shoals experience was critical for their development. They spent time in the studio with producer Jimmy Johnson, one of the best, learned how to arrange and record songs and further developed a work ethic which would serve them well. Allen and Gary came up with some of the greatest riffs in Rock history, but they would have acknowledged that there were better players out there. Ronnie’s voice was strong and distinctive, but he would have tipped his hat to singers with greater vocal range. They would have all kicked your butt, however, if you called them lazy. No band in Rock history worked harder than Lynyrd Skynyrd and as a live band there wasn’t anyone better.

Despite all of this, by the beginning of 1973, outside of the Southern club and bar circuit, Skynyrd was still relatively unknown. They had been at this for several years now, but had little to show for it. Then it happened. In early 1973 Ronnie and the boys were given a chance to play as the house band for a week at a club called Funochio’s in Atlanta. By Allan Walden’s account, this was the premier spot in Atlanta for drug addicts to hang out and get their fix. In other words, if Skynyrd could get the audience more interested in music than drugs, they could make it anywhere. True to form, Ronnie and the boys went to work and delivered.

In the audience one night was Al Kooper. Kooper was already a successful musician from New York, having most famously founded Blood, Sweat and Tears in 1967. Now, Kooper had turned his attention to producing and recording in addition to performing and he was in Atlanta to work with an early incarnation of the Atlanta Rhythm Section. He listened to Skynyrd, liked what he heard, and soon joined them on stage.

It was 1973, and what dominated the rock charts at that moment was Progressive Rock; bands like Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Prog Rock featured long, almost classically composed music, expert musicianship, and ponderous lyrics with often fantastical or science-fiction themes. In fact, this was the very brief golden age of Prog Rock, which would develop a devout following, but be utterly despised by Rock critics.

Al Kooper had come up playing blues, jazz and R&B. He thought this Prog stuff was kind of soulless and what he heard in Skynyrd was an antidote; a heavy, meaty, aggressive, Southern-American version of the British band Free; a sound rooted in old fashioned rock n’ roll. And, of course, there was Ronnie, whose stage presence, voice and lyrics struck Al as being raw, powerful and ‘real.’ Skynyrd was what Rock music needed at the time.

Thus began one of the most fruitful, and profitable, relationships in Rock history. Kooper decided to start his own label to feature Skynyrd and other Southern bands he might discover. This was Sounds of the South Records, later bought out by MCA. Kooper would become an essential part of Skynyrd’s success. His relationship with the members of the band, particularly Allen, wasn’t always sweet, but he and Ronnie had a connection. These were two guys who, on paper, might appear to have had little in common but developed a real friendship and sincere respect for each other as artists.

Kooper produced the first three albums, 1973’s Pronounced ‘Leh-nerd Skin-nerd’, 1974’s Second Helping and 1975’s Nuthin Fancy. More albums and great songs from the band were to come, but by the time Kooper and Skynyrd parted ways, most of the band’s classic rock anthems had been recorded.

While it’s important to acknowledge Skynyrd’s musical debt to British bands like the Stones and Free, the traditional country, blues and Southern roots influences abound in Skynyrd’s music. When it comes to Ronnie’s lyrics those were uniquely Ronnie Van Zant, and they were undeniably Southern. I don’t know if Ronnie Van Zant ever read a single book by William Faulkner, Flannery O’Conner, Robert Penn Warren, or any of the others in the pantheon of Southern Literature. We shouldn’t automatically assume he didn’t at some point, because he could have encountered these or other writers as a student along the way. Everyone who seriously knew Ronnie remembered him as smart, perceptive and creative, the personality type who tends to be a writer or student of literature. If I had to compare Ronnie’s lyrics to a Southern author it might be Harry Crews or, if we want to go back further, to George Washington Harris, Johnston Jones Hooper or Augustus Baldwin Longstreet. Ronnie would have fit right into the Southwestern humorist tradition. If you’ve ever read Longstreet’s Georgia Scenes you’ll understand. But even if Ronnie never cracked open a book in his life, it doesn’t matter. Great literature doesn’t come from other literature. It comes from life. Its Ronnie’s unique take on life as revealed in his songs that makes them great and deserving of inclusion in the long tradition of Southern artistic expression.

Several themes occur in Ronnie’s lyrics. These themes also permeate the Southern literary tradition; the importance of family, a deep connection to the land, to place, the presence of the past, a stoic resolve to take life as it comes, and the recognition of humanity’s fallen nature, and the ability to point that out, and even laugh at it when called for. We find these emerging on the very first album, Pronounced. For many, “Sweet Home Alabama” is Skynyrd’s signature anthem, but I think a better candidate for Ronnie’s personal statement is “Simple Man.”

Mama told me when I was young

“Come sit beside me, my only son

And listen closely to what I say

And if you do this it’ll help you some sunny day”“Oh, take your time, don’t live too fast

Troubles will come and they will pass

You’ll find a woman and you’ll find love

And don’t forget, son, there is someone up above”“And be a simple kind of man

Oh, be something you love and understand

Baby be a simple kind of man

Oh, won’t you do this for me, son, if you can”“Forget your lust for the rich man’s gold

All that you need is in your soul

And you can do this, oh baby, if you try

All that I want for you, my son, is to be satisfied”“And be a simple kind of man

Oh, be something you love and understand

Baby be a simple kind of man

Oh, won’t…

When Ronnie wrote this, Skynyrd had yet to make it big, but one can sense he was already contemplating how future success might change him, and it worried him. To head off the inflated ego that fame could bring, Ronnie was looking to home, and to the values his mother taught him. We can read “Simple Man” as an expression of Southern stoicism. Troubles will come, and they will go. Fame and fortune may come, but what are they if you don’t have roots, if you don’t know who you are or where you come from? Notice that Mama doesn’t tell her son to be simple, or simple-minded, but a simple kind of man. Human affairs may be complex to the point of incomprehension, but what makes for a good life is still and always to be found in the simple virtues and simple pleasures.

Mama is a symbol of home and family. Family and friends and affection for and connectedness to home and to place are everywhere in Ronnie’s songs. You hear it in what is probably my favorite Lynyrd Skynyrd song, “Am I Loosing” off 1975’s Nuthin Fancy. After coming off tour to support Second Helping, MCA wanted another album right away. So in January of 1975 they went into Studio One in Doraville, Georgia with only one song already done, “Saturday Night Special” which had been recorded the previous year and famously used in the opening scene of the Burt Reynolds’ film The Longest Yard. They had less than a month to write, record and mix an entire album of new material.

The pressure of recording Nuthin Fancy was enough for Kooper. It was the last he produced for the band, saying he would rather be their friend than their producer. The band themselves, as well as music critics, have tagged it as their least impressive effort. Overall, however, it’s my favorite Skynyrd album with the next, Give Me Back My Bullets, in second. I hear so much in these two albums that sounds like later Americana but just harder and meaner.

The inspiration for “Am I Losing” may have been the departure of drummer and old friend Bob Burns from the band. Burns had played badly one night on the road, and Ronnie had chewed him out royally. This caused Burns to have a mental breakdown and soon afterward he quit. In the song, I think you hear some regret on Ronnie’s part, but there is also a return to the theme of “Simple Man.” Now that success has come, is he not living by what Mama told him? Is Burns’ leaving a sign that he is losing touch with where he came from and the people he grew up with on the Westside? It’s a deeply heartfelt song, and Ed King’s guitar work just nails the mood.

In “Every Mother’s Son” off of Give Me Back My Bullets you hear the same lament for fractured friendships and strained lives caused by success and getting above your rasin’. The antidote to all of this is to put things in the proper perspective, one which Mama in “Simple Man” would’ve validated. These three songs, “Simple Man,” “Am I Losing” and “Every Mother’s Son,” form a sort of trilogy, a meditation on loyalty to family and friends.

The South and Southern places and Southern people are also everywhere in Ronnie’s songwriting, and no place looms larger that Alabama in how Ronnie and Skynyrd are remembered. If the casual fan out there has heard anything by Skynyrd its “Free Bird” off of Pronouned or “Sweet Home Alabama” off of Second Helping. “Free Bird” is the epic guitar jam that showcases Allen Collins’ guitar playing. Lyrically it’s a fine song, but it’s the guitar work that is the focus along with pianist Billy Powell’s iconic accompaniment. It’s important to remember that while the beginnings of “Free Bird” can be traced back to 1971, it was only by playing it live in the mid 70’s that the song became a classic rock anthem. Its influence has been massive. There wasn’t a single six-string gunslinger in denim or spandex walking L.A.’s Sunset Strip in the 1980’s looking to join a band who didn’t cut his teeth playing “Free Bird.” It went beyond L.A. too. When a young Steve Clark auditioned for Joe Elliot in 1978 to join his new band Def Leppard in Sheffield, England, what he played was “Free Bird.” It got him the job.

But its “Sweet Home Alabama,” that more than any other song has come to represent Skynyrd, and I’d have to argue, as a Southern song, it’s the “Dixie” of the Rock N’ Roll Era, made so by the love of countless Southern fans. But there you have it. It’s also been called Lynyrd Skynyrd’s most controversial song, and it’s typically been what critics point to when they wish to argue that Ronnie and Lynyrd Skynyrd weren’t just North Florida rednecks who liked to drink and fight. They were racists too. The song’s lyrics and the band’s use of the Confederate flag as a backdrop in concerts and elsewhere have been cited as conclusive proof of this. I want to address this notion of ‘controversy,’ but first some context is needed.

Early in the recording process of the Pronounced album bassist Leon Wilkerson quit. Apparently Leon wasn’t sure if he could make the kind of commitment necessary to see the thing through and, as a devout Christian, he wasn’t sure the life of a rock star was going to be consistent with his faith. Ronnie tapped a fellow named Ed King to be Leon’s replacement. Ed was a California native from Glendale who had been a member of a hippie-vibed, psychedelic-pop fusion band named The Strawberry Alarm Clock which had had a hit song in 1967 with “Incense and Peppermints.”

Since then, the band’s fortunes had tanked, and it was during a final tour doing some shows at various Southern colleges, shows that Skynyrd were also doing, that Ronnie met Ed. They immediately struck up a friendship, and Ed offered his services to Skynyrd if Ronnie ever needed them. Ed was a guitarist, but what Ronnie needed at the moment was a bassist, so Ed took the job. (Sometimes you hear people say that Ed was the only non-Southerner in Skynyrd. That’s not true. Larry Junstrom, who was the bassist in The One Percent and then Lynyrd Skynyrd, was originally from Pennsylvania. He later became the bassist for .38 Special.)

By this time, Skynyrd were rehearsing in a small, rented cabin on Peter’s Creek in Green Cove Springs, Florida about 30 miles south of Jacksonville. It was an isolated, rural area with moss in the live oaks and alligators in the creek. Ronnie liked it because the band could get away from people, be as loud as they wanted, and he could go fishing while the rest of the boys worked on arrangements, solos and new material. They had had some equipment stolen, so for his first task, the band told Ed he had to spend the night an entire week at the cabin. This was the legendary Hell House. It was November 1972. Ed was so terrified of the swamp noises he heard outside he left the lights on the whole week. One night a gator came up to the cabin, and Ed had to go get the man who owned the place come and shoot it. So, this California kid who just a few years before was wearing hippie outfits and playing a hit song about incense and peppermints was now alone in a Florida swamp fighting off alligators. Welcome to Skynyrd!

This is where Sweet Home Alabama was written. As Ed remembers it, the band would arrive between 8:00 and 9:00 in the morning and work straight into the evening, almost every day, with military-like discipline; no drinking, no drugs, no girlfriends, just the band and the music. Work on the Pronounced album was done in early May of 73 with the release in August. So the band was spending the summer of 1973 deep in the Florida woods working on new material, in the heat and humidity, with the flies, bellowing alligators and the constant ring of guitars and crash of drums, in this tiny cabin with no air conditioning.

One day in June magic happened. First, Leon came back. He had been working in an ice cream factory in Jacksonville, but Ronnie had talked him back into the band. As soon as Ed showed up that morning, he heard Gary playing an interesting riff on an acoustic guitar. Immediately, Ed complimented it with something he had been toying with. And there it was; the iconic opening riff to “Sweet Home Alabama.” Ronnie told them to keep playing it over and over while he thought of some lyrics.

He sat in the corner of a little sofa, head in his hands. Ronnie never wrote his lyrics down, saying if they weren’t good enough to remember they weren’t good enough to sing. In just a few hours it was all done. The song was written. Ed’s solo in the song is something he claims to have heard note for note in a dream. They knew right then it was going to be a hit. Ronnie later told Ed “There’s our Rambling Man,” a reference to The Allman Brothers hit song. Ronnie quickly called Al Kooper and said the band had a great song and they wanted to record it right away. When he first heard it Kooper too knew it was a hit.

Ronnie’s reference to “Ramblin Man” is significant. Skynyrd was at that moment still a road band, with no hits and no radio play. Ronnie was looking for a hit record, but obviously inspiration came to him from what was going on in 1973. The country had been riveted by the Watergate hearings that May. They had been carried live on T.V. by all the networks when there were only three of them. They had left a sour taste in many people’s mouths, Ronnie’s among them.

Let’s take a careful look at these lyrics:

Big wheels keep on turning

Carry me home to see my kin

Singing songs about the Southland

I miss Alabamy once again

And I think it’s a sin, yes

Here the narrator of the song is a homesick singer from Alabama, who sings songs from and about the South, on a tour bus headed back home, but he feels guilty for missing such a place as “Alabamy.” In fact, it’s a “sin.” Well, why is that? Because of Neil Young.

Well I heard mister Young sing about her

Well, I heard ol’ Neil put her down

Well, I hope Neil Young will remember

A Southern man don’t need him around, anyhow

Is this Ronnie himself, or is it a character Ronnie has created who is speaking? I think it’s a little of both. Neither Ronnie nor any of the other Skynyrd members were from Alabama, but Ronnie was a Southerner already singing some songs about the Southland. It’s interesting to note that the first Southern state featured in one of Ronnie’s song wasn’t Alabama but Mississippi, in Pronounced‘s “Mississippi Kid.” In that song a tough Mississippi kid announces:

I’ve got my pistols in my pockets boys, I’m

I’m Alabama bound

Well, I’m not looking for no trouble

But nobody dogs me ’round

Now, in “Sweet Home Alabama,” Ronnie isn’t warning Alabama, he is defending her in his riposte to Neil Young. Young had recorded two songs that Ronnie references here, “Southern Man” from his 1970 album After the Gold Rush and “Alabama” from 1972’s Harvest. Ronnie knew these songs, of course, because he was a fan of the Canadian singer/songwriter. In “Southern Man,” Young sings:

Southern man

better keep your head

Don’t forget

what your good book said

Southern change

gonna come at last

Now your crosses

are burning fast

Southern manI saw cotton

and I saw black

Tall white mansions

and little shacks.

Southern man

when will you

pay them back?

I heard screamin’

and bullwhips cracking

How long? How long?

Young is clearly laying upon Southerners a legacy of slavery, Jim Crowe and racism, and doing it in a very singular way, the implication being racism is the defining attribute of being a Southern man, and it is he would has to atone for this sin.

In Alabama, Young had sung:

Alabama

You got the weight on your shoulders

That’s breaking your back

Your Cadillac

Has got a wheel in the ditch

And a wheel on the trackOh, Alabama

Banjos playing through the broken glass

Windows, down in Alabama

See the old folks

Tied in white robes

Hear the banjo

Don’t it take you down home?

This is Tobacco Road, ‘Snuffy Smith’, Deliverance imagery here.

In “Sweet Home Alabama,” after signaling that he’s heard all of this, Ronnie tells Young where to get off. Instead of anger, however, I think we should hear Ronnie’s tone as it was intended. It’s playful. In several interviews Ronnie made that clear. Ronnie was a fan, and in later years when performing “Sweet Home Alabama” he would wear a Neil Young T-Shirt. (Legend has it he was buried in one). Ed King also remembers Ronnie asking him what he thought Neil would think of the lyric. Ed told him he though Young would get the joke. In his autobiography, Waging Heavy Peace, Young said he thought the song was more a response to “Alabama” than “Southern Man” and said he, “richly deserved the shot Lynyrd Skynyrd gave with their great record. I don’t like the words when I listen to it. They are accusatory and condescending.” That’s doubtless how Ronnie heard them.

In the second verse of “Sweet Home Alabama,” we perhaps have the more ‘controversial’ lines:

In Birmingham they love the governor, (boo! boo! boo!)

Now we all did what we could do

Now Watergate does not bother me

Does your conscience bother you?

Tell the truth

The governor, of course, was George C. Wallace, who had stood in the doorway in Tuscaloosa to oppose the integration of the University of Alabama in 1963 and had run for president as an independent in 1968. In the 1972 election, Wallace ran again, but for the Democratic nomination, and had refocused his message. Instead of now being identified as simply an Alabama segregationist, he was reaching out to a national electorate with a broader populist appeal. And it was working. He won the primaries in Florida, Tennessee, North Carolina and Michigan. On May 15, 1972, Wallace was shot in Laurel, Maryland, effectively ending his campaign, although he did win the Maryland primary too. A little over a year later, Ronnie was writing “Sweet Home Alabama.”

I have no idea if Ronnie voted in the 72 Florida Democratic primary, but I would imagine that a lot people on the Westside of Jacksonville did, and most probably voted for Wallace. Those blue-collar, working-class people were exactly who Wallace appealed to. This raises the question of what was in Ronnie’s mind that day in June of 73 as he sat on the sofa in Hell House composing lyrics to accompany Ed and Gary’s playing, and how listeners at the time interpreted the song. We should recognize that these are two different things, but accept that disentangling them completely isn’t possible.

One can imagine Wallace, particularly after he was shot, serving as a kind of symbol for white Southerners, even if they hadn’t agreed with everything he had said and done, although certainly many had. Coming out of the 60’s, these Southerners had felt the sting of harsh, negative stereotypes from the larger national culture. They felt misunderstood, insulted and defamed. I think on a certain level Ronnie felt this too. Add to it, though, Neil Young’s condescension, from an artist Ronnie respected, and it stung in a personal way. And then, there is the reference to Watergate, which many who analyze the song overlook, but which is a key to Ronnie’s intent in “Sweet Home Alabama.”

An interviewer once asked Ronnie his opinion of Wallace. “Wallace and I have very little in common,” Ronnie said, “I don’t like what he says about colored people.” That seems a fairly definite statement, although the line “In Birmingham they love the governor, Now we all did what we could do.” is ambiguous. Many Southern listeners at the time may have heard it as simply an assertion of survival during those tumultuous years.

In the context of 1973, I think Ronnie is using Wallace, consciously or not, as a symbol. It’s as if Wallace had been shot for the shortcomings and failures of the South in Civil Rights Era, but for those who admired Wallace, especially for his more populist turn by 72, they could also hear in it a note of tragedy because it foreclosed a nascent hope that something different, and something good, could have come from him and their region; a new synthesis of what they liked about Wallace but in the changed circumstances of the 70’s. Carter, with his softer, “A Government as Good as Its People” style populism, may have benefited somewhat from this in 76. Carter wasn’t Wallace, but a lot of Southerners who voted for Wallace in 72 didn’t in 76 but instead voted for fellow Southerner Jimmy Carter who, of course, Wallace later endorsed. Obviously as well, the attempted assassination of Wallace would have been linked in their imaginations with the successful assassinations of JFK, RFK and King.

I suspect that for some Southerners in 1974 “Sweet Home Alabama” served as an emotional catharsis for their experience of that whole era, but from Ronnie it’s also a snarky defense at the same time. Look, Ronnie is saying in the song, I’ve had it. I’m rising to the defense of Alabama, and by extension my people, Southerners. You think we’re uniquely bad? You want to dump all the sins of the country on us? Look at what’s happening in Washington. We should have our consciousness raised? Well, look at Watergate, does your conscious bother you? We Southerners, symbolized by Wallace and Alabama, didn’t have anything to do with that. That’s Nixon from California, who won the 72 election in a whopping national landslide.

Notice Ronnie doesn’t say that Alabama, or the South, is pure and sinless. He does, however, name the ‘Swampers’ from Muscle Shoals who have contributed great richness to American music. So, if you want to dump on Alabama think about what you might be burying in the process. The sin in this country is everywhere, and we’re all caught up in it. Take a look at yourself in the mirror and get off our backs.

Al Kooper claims to have been responsible for adding the “Boo, Boo, Boo” which follows “In Birmingham they love the governor.” I think if Ronnie intended the line to be unequivocally supportive of Wallace he would have objected to that inclusion, but he and the band thought it was a clever addition.

They also wrote “I Need You” the same day they wrote “Sweet Home Alabama.” It comes right after “Sweet Home Alabama” on Second Helping. It’s a classic love ballad. This might tell us something about the spirit in which “Sweet Home Alabama” was written. It seems incongruous to imagine Ronnie pumped into a furious rage at Neil Young while composing “Sweet Home Alabama,” only to turn immediately to writing a sweet, doleful love song. I think “Sweet Home Alabama” is comparable in some ways to Charlie Daniels’ “Uneasy Rider,” also from 1973. There’s some poking going on all around, some tongue in cheek, and enough space for listeners to provide their own take.

This brings us to flag. At some point in 1974 the band started performing with a large Confederate flag as a backdrop. Why they did this at this time is a point of contention. Al Kooper, a reliable source on all things Skynyrd, claims it was the bands’ idea. They wanted to do it because they felt it represented who they were and their Southern roots. Others claim they were told by Ronnie himself, that it was, in fact, the idea of the marketing people at MCA. When “Sweet Home Alabama” was released as a single on June 24, 1974 the sleeve for the 45 featured a set of feminine lips with a Confederate flag dripping out of them. I don’t imagine the band had much input into the design by the art department at MCA. Even if using the flag had been solely the band’s idea, MCA Records certainly didn’t have a problem using it. During the 1975 “Torture Tour”, the band would open by playing a rendition of “Dixie” with Ronnie wearing a grey Confederate officer’s coat and hat. No one at MCA threatened to drop the band if they didn’t stop.

That same year, as “Sweet Home Alabama” was all over the radio, Governor Wallace made the whole band honorary Lt. Colonels in the Alabama state militia. Ronnie did later described this as a, “bullshit gimmick thing.” And, it seems that sometime in 1976 or early 1977 the band moved away from using the flag in concert, although you can see photos from that time where Ronnie or Allen are wearing T-shirts with the flag on it.

I don’t think their initial use of the flag was insincere, although it’s possible that using it in the particular way they did might not have been their idea. These boys were Southerners (other than Ed), and they were young Rock N’ Roll rebels, who would have grown up revering the flag as a symbol of the fighting spirit of the South. Nor do I think they moved away from it out of shame or embarrassment. In fact, it might have been out of reverence, a sense that they might have been dishonoring it somehow by using it as a kind of token. More to the point, in interviews from this period Ronnie complained that all journalists ever wanted to ask him about was the drinking, the fights, the smashed hotel rooms, the off-stage drama; everything except the music, and by 1976 Ronnie and Lynyrd Skynyrd had matured as musicians and as a band. Ronnie wanted to be taken seriously as an artist. He wanted the music to be the focus. He wouldn’t have wanted people to think of Skynyrd as just the ‘rebel flag’ band.

We should add that while today people refer to all of this as “controversial,” in the 1970’s it simply wasn’t. Were there a handful of people upset by some of this? Maybe, but a handful does not make a controversy. This has more to do with contemporary attitudes about the flag and Confederate symbols than how these things were perceived then. “Sweet Home Alabama” was a top ten hit nationwide, peaking at #8. And, the Confederate flag was everywhere in the 1970s. It was a staple of American popular culture, especially in the South, but not exclusively. It was also on hats, T-Shirts, belt buckles, shot glasses, hanging in dorm rooms and from fraternity houses everywhere. In the form of the Georgia state flag it appeared on the front of Burt Reynolds’s black 1977 Pontiac Trans Am in Smokey and the Bandit. It was on the roof of the General Lee, the iconic 1969 Dodge Charger from The Dukes of Hazzard. Even if you say all of this was Good Ole Boy, redneck kitsch, it was seen as charming and fun and nobody much had a problem with it.

Was “Sweet Home Alabama” a political song? Only in the most narrow sense. If you wanted to find a political Skynyrd song you might take a look at “Saturday Night Special” from Nuthin Fancy. “Saturday Night Special” is Ronnie’s Southern Gothic Noir masterpiece.

Two feet they come a creepin’

Like a black cat do

And two bodies are layin’ naked

A creeper think he got nothin’ to lose

So he creeps into this house, yeah

And unlocks the door

And as a man’s reaching for his trousers

Shoots him full of thirty-eight holesMr. Saturday night special

Got a barrel that’s blue and cold

Ain’t good for nothin’

But put a man six feet in a holeBig Jim’s been drinkin’ whiskey

And playin’ poker on a losin’ night

And pretty soon ol’ Jim starts a thinkin’

Somebody been cheatin’ and lyin’

So Big Jim commence to fightin’

I wouldn’t tell you no lie

Big Jim done pulled his pistol

Shot his friend right between the eyesMr. Saturday night special

Got a barrel that’s blue and cold

Ain’t good for nothin’

But put a man six feet in a holeOh, it’s the Saturday night special, for twenty dollars you can buy yourself one too

Hand guns are made for killin’

They ain’t no good for nothin’ else

And if you like to drink your whiskey

You might even shoot yourself

So why don’t we dump ’em people

To the bottom of the sea

Before some ol’ fool come around here

Wanna shoot either you or meMr. Saturday night special

You got a barrel that’s blue and cold

You ain’t good for nothin’

But put a man six feet in a holeMr. the Saturday night special

And I’d like to tell you what you could do with it

And that’s the end of the song

Here we’ve got murder, betrayal, alcohol fueled rage, violence and death. This is the ugly, dark side of the human animal, and it’s very much an expression of the mean under-toe of the 1970’s, of rising crime rates, the latest local murder on the 6 ‘Clock News, of “if it bleeds it leads headlines.” Recall this is the era of Charles Manson, the Zodiac killings and the Son of Sam. There were lots of creepers creeping about. This is Ronnie’s inspiration here, although it’s not just from the news. Rap artists often say that the violence described in their lyrics is just a reflection of the world they’re from. Ronnie’s drawing from the world he came from too, the rougher parts of Jacksonville and the mean streets of 1970’s America, of bar fights with switchblades and pawn shop pistols. He knew what the inside of a jail looked like. He’s been in a few. He knew what it felt like to be shot, because he had been. Ronnie’s lyrics were rarely autobiographical in a literal sense, but instead were collages based on definitely real experiences.

The focus here, of course, is on those cheap, Saturday night specials, a snub-nose .38, or something like it, that you could buy at a pawn shop in a fit of rage and then kill an ex-lover or her new boyfriend, or even turn around and use to rob the pawn shop. Ronnie knew those kinds of stories.

Skynyrd fans have long debated if Ronnie really meant dumping them all into the sea. Could Ronnie really be suggesting gun control? An interviewer once asked Ronnie that very question, and he answered unequivocally yes. But, he quickly qualified that by saying he owned a gun himself, an old 1874 Springfield he had hanging on his mantle. (He didn’t mention the .22 pistol he also owned, used for shooting snakes when fishing, but maybe one that could serve as a Saturday night special in a pinch too.) Hand guns, ‘saturday night specials,’ however, were different, because, as the song says, they were made for killing other people, and had no sporting use.

You can agree or disagree with Ronnie’s sentiment here, but in the context of the song you’re left wondering what else would the narrator say? “Saturday Night Special” isn’t the high school debate team’s take on ‘the gun issue.’ I don’t hear a political agenda here, but a frustrated suggestion born out of a dark journey through the human underbelly.

For my money, “Saturday Night Special” is Skynyrd’s hardest rockn’ song, even more so than “Free Bird.” The guitars from Ed, Allen and Gary are just ferocious and unrelenting. It has a groovy, Funk-like beat, and sonically it’s definitely a song of the 70’s, but the dark, mean guitar tones and the three guitar, fret-board assault point toward the aggressive approach of later hard rock and heavy metal. Apparently, the band recorded an extended version of the song, longer than the album version. In it, Ed, Allen and Gary let it rip for an additional couple of minutes, ala “Free Bird.” Very sadly, those tapes were lost.

You have a comedic counterpoint of sorts to “Saturday Night Special” in “Gimme Three Steps” from the Pronounced album. The narrator is at place called the ‘Jug’ (There was a place in Jacksonville called the ‘Little Brown Jug’) putting the moves on another man’s woman, when her man comes in, with a gun in his hand, looking for her and sees the scene. He sticks a .44 in his face which leads the narrator to ask for just one favor, “give me three steps and you’ll never see me no more.” For an artist with such a ‘macho’ image, this is Ronnie’s ode to the occasional virtue of cowardice and self-preservation. It’s the most humorous of Ronnie’s songs.

Our theme, however, is the South and Southern places and what they meant to Ronnie. Take a listen to “Swamp Music” off Second Helping. It’s a full on celebration of the swamp, a landscape classically identified as emblematic of the South, and sometimes with less than sympathetic associations, a place of yellow fever, dangerous snakes and alligators, criminals, fugitives, and useless to agriculture. Simultaneous to this, however, is another tradition in Southern literature celebrating the mystery and natural beauty of swamps. The great 19th Century Southern writer William Gilmore Simms featured the swamps of his native South Carolina in numerous poems and stories. Those dense, dark swamps also afforded General Francis Marion protection during the Revolution so that he could attack the British with inferior forces and retreat to safety.

I suspect that Ronnie would have heard the great Georgia singer and guitarist Jerry Reed’s 1970 song “Amos Moses” whose subject lived by himself in a Louisiana swamp, hunting alligators for a living by knocking them in the head with a concrete stump of arm up to the elbow. The association in Reed’s song is between swamps and freedom. We hear a similar note in Ronnie’s “Swamp Music.”

What’s especially interesting is the shout out Ronnie gives to Edward James House, Jr., or Son House, the legendary bluesman from Mississippi. He compares the barking of his dogs on a coon hunt to Son House singing the blues and announces that he’d rather live with hound dogs for the rest of his life, to remain in this idyllic swamp landscape. Here we have the linking of coon hunting, fishing, blues music and the richly symbolic Southern swamp landscape all in one package.

Ronnie knew his sources, he knew his music history, and he respected that history. That’s very much on display in “The Ballad of Curtis Loew,” also from Second Helping. The song was not a hit at all, and the band only played it once live, but it has since become a favorite among serious Skynyrd fans. I think the song is Ronnie at his best as a songwriter. It’s personal, narrative storytelling with a strong tug on the heartstrings.

Well, I used to wake the mornin’

Before the rooster crowed

Searchin’ for soda bottles

To get myself some dough

Brought ’em down to the corner

Down to the country store

Cash ’em in, and give my money

To a man named Curtis LoewOld Curt was a black man

With white curly hair

When he had a fifth of wine

He did not have a care

He used to own an old Dobro

Used to play it ‘cross his knee

I’d give old Curt my money

He’d play all day for mePlay me a song

Curtis Loew, Curtis Loew

Well, I got your drinkin’ money

Tune up your Dobro

People said he was useless

Them people all were fools

‘Cause Curtis Loew was the finest picker

To ever play the bluesHe looked to be sixty

And maybe I was ten

Mama used to whoop me

But I’d go see him again

I’d clap my hands, stomp my feet

Try to stay in time

He’d play me a song or two

Then take another drink of winePlay me a song

Curtis Loew, Curtis Loew

Well, I got your drinkin’ money

Tune up your Dobro

People said he was useless

Them people all were fools

‘Cause Curtis Loew was the finest picker

To ever play the bluesYes, sir

On the day old Curtis died

Nobody came to pray

Ol’ preacher said some words

And they chunked him in the clay

Well, he lived a lifetime

Playin’ the black man’s blues

And on the day he lost his life

That’s all he had to losePlay me a song

Curtis Loew, hey Curtis Loew

I wish that you was here so

Everyone would know

People said he was useless

Them people all were fools

‘Cause Curtis you’re the finest picker

To ever play the blues

Was there an old bluesman who schooled Ronnie in music? Yes and no. The real Curtis Loew was a composite of several people, but certainly among them was Claude H. “Papa” Hamner who owned a small grocery store in Jacksonville that Ronnie visited and worked at as early as 8 or 9 years old. Hamner grew up on a farm in Colquitt County, Georgia and moved to Jacksonville in 1952 and worked for the railroad until opening the grocery store. Hamner had taught himself to play the guitar. If you could hum it, he could play it and he loved playing songs like “Wildwood Flower” for his children and the neighborhood kids, Ronnie among them. Hamner actually taught Ronnie to play the guitar some and called Ronnie his ‘bottle boy’ because Ronnie’s job was to sort the soda bottles by brand and sweep up.

Another inspiration was Shorty Medlock, a popular country/bluegrass musician in Florida during the 1950’s. Shorty, another Georgia native, had been a sharecropper and was the grandfather of Ricky Medlock, a one-time Skynyrd band member (and current band member) and the lead singer for Blackfoot, another hard rockn’ 70’s Southern band from Jacksonville. Shorty played guitar, dobro, banjo, fiddle and harmonica and used to have jam sessions on his front porch attended by Ronnie, Allen, Gary, and of course, Ricky. Ronnie dedicated the Nuthin Fancy album to Shorty, and the song “Made in the Shade” is a tribute to him.

The interesting thing here is that Claude Hamner and Shorty Medlock were white men. In the song, however, Ronnie sings the praises of old Curtis, a forgotten Black bluesman who Ronnie says was the finest picker to ever play the blues. He’s clearly referencing Rufus “Tee-Tot” Payne, the legendary Alabama blues player who taught Hank Williams to play. And there’s Robert Johnson too. In essence, Ronnie was paying tribute to the whole Southern musical tradition in “The Ballad of Curtis Loew,” of every player who sat on a porch and picked a tune, some who made it big, but most who are forgotten. He wanted to be a part of that tradition. He was also clearly signaling that Blacks and Whites were inseparably linked in that tradition. Think about it, while primarily influenced personally by Hamner and Medlock, the praises fall on the fictional Curtis. When Hamner’s son Vernon first heard the song, he wasn’t shocked or outraged at this. He said, “That’s my daddy.”

Jacksonville in the 1970’s was a rapidly growing Sun Belt metropolis in the throes of suburban sprawl. The same thing was happening all over the South in what historian C. Vann Woodward had termed ‘The Bulldozer Revolution.’ Suburbs with names like Pine Lake, Happy Meadows, and Oak Forrest were being built on the outskirts of cities throughout the South. (It’s funny how subdivisions are named after the things they destroy.) With them came the shopping centers, strip malls, fast food restaurants, the interstates, by-passes and cross-town connectors. Ronnie saw this change taking place and hated it. He viewed this as destroying an older South, a rural and wild landscape that he cherished and which had helped form him.

“All I Can Do Is Write About It” from 1976’s Gimme Back My Bullets is Ronnie’s plaintive, nostalgic lament for this loss. It’s the sort of song that only die-hard Skynyrd fans will know. It wasn’t a hit, and I don’t think they ever performed it live. It’s the most country-sounding song that Skynyrd recorded. In fact, it’s far more country than anything heard on ‘country’ radio today. The producer of Gimme Back My Bullets, Tom Dowd, considered it a masterpiece, and it’s one of my favorites.

Lyrically, I think this is Ronnie’s deepest expression of his Southern spirit.

Well this life that I’ve lead has took me everywhere

There ain’t no place I ain’t never gone

But it’s kind of like the saying that you heard so many times

Well there just ain’t no place like homeDid you ever see a she-gator protect her young’ns

Or a fish in a river swimming free

Did you ever see the beauty of the hills of Carolina

Or the sweetness of the grass in TennesseeAnd lord I can’t make any changes

All I can do is write ’em in a song

But I can see the concrete slowly creepin’

Lord take me and mine before that comesDo you like to see a mountain stream a-flowin’

Do you like to see a young’n with his dog

Did you ever stop to think about, well, the air your breathin’

Well you better listen to my songAnd lord I can’t make any changes

All I can do is write ’em in a song

But I can see the concrete slowly creepin’

Lord take me and mine before that comesI’m not tryin’ to put down no big cities

But the things they write about us is just a bore

Well you can take a boy out of ol’ dixieland

But you’ll never take ol’ Dixie from a boyAnd lord I can’t make any changes

All I can do is write ’em in a song

I can see the concrete slowly creepin’

Lord take me and mine before that comes

‘Cause I can see the concrete slowly creepin’

Lord take me and mine before that comes

Ronnie clearly roots his Southern identity in his love of the land. You can take a boy out of ole Dixieland, but you’ll never take ole Dixie from a boy. You can imagine a young Ronnie roaming the North Florida woods outside Jacksonville with his buddy Gene, hunting squirrels, or fishing in Cedar Creek, catching Bream on a cane pole, breathing in the fresh, humid air and realizing this was who is was. You can imagine it, because those were things Ronnie actually did, and he was seeing that experience being steadily covered with concrete and asphalt and soon gone forever. He doesn’t know what to do about it, again there’s no political agenda attached, but he knows what his heart is telling him. That heart would be broken to learn that the wild countryside where Hell House was at is now an exclusive, up-scale housing development called Edgewater Landing.

In the 1970’s you are beginning to have environmentalist sentiments enter the popular culture. Recall the now famous Keep America Beautiful commercial with Iron Eyes Cody as the ‘crying Indian,’ paddling his canoe up a litter-strewn river and having trash tossed at his feet as he stands before a busy highway. You also might think of Joni Mitchel’s 1970 song “Yellow Taxi” where she says they “paved paradise and put up a parking lot.” But, the Keep America Beautiful commercial is vague and abstract. “Keep America Beautiful, don’t litter.” Ronnie’s song, however, is more ambitious and specific in what h

I enjoyed reading this article. The information imparted a heartfelt view of soul that was Ronnie Van Zant. It is very informative and descriptive. Thank you for the insights into his art.