A few days ago I ran into an old friend, an historian, who started in on the Partisan. “I’ve lived all my life in the South,” he grumbled, “but I don’t see what makes Southern life so wonderful that you and your friends want to impose it on the rest of the country.” I did my best to reassure him that nothing was further from our intention than any form of standardization—whether making the South like New England or vice-versa. He seemed somewhat mollified. Still, his remark set me to thinking about the great gulf between educated Southerners (like my friend the historian) and those plain folks we have learned to despise as rednecks, grits, and crackers.

We are in a period of time, when most affluent and educated Southern people have come to identify their interests with members of their own class in the Northeast and California, instead of with their region. They are, by and large, proud of urbanization (still more of suburbanization), commercial culture, and the values of liberation which characterize life in Atlanta and its Northern originals. Among such people, it is a race to see who can give up the most first (a reversal of “First with the Most” Forrest’s strategy): collards are replaced by spinach and mushroom salad, Country Music by Rod Stewart and Paul Simon (if you’re under 40), Wayne Newton (if you’re older), and regional dialects by a way of speaking that resembles a cross between Dan Rather and a California car salesman. A very decent businessman confessed to me recently that he hated to hear his own voice on a tape (sounded like a cracker) and always preferred to hire an actor with a “neutral accent” for any promotions.

But meanwhile, down on the farm and up at the mill, the plain folks are turning on their radios and listening to songs that amount to a Declaration of Independence from Yankee urbanity. Mixed in with the usual odes to adultery and divorce—pick-up trucks and picking up girls—are songs with a clear-cut social message: everything good, true, decent, and enjoyable is Southern or rural; and everything bad, false, rotten, and boring is found in Northern cities. It is not just Southerners who are getting this message, but all of rural and small town America.

Some of the songs are the usual tin pan alley stuff—in the same class with “Mammy” and “Rock-a-bye your baby with a Dixie Melody”—”Whispering” Bill Anderson’s “Southern Fried” is a good example; others express a genuine and sentimental affection for the South—like Charlie Daniels’ “Carolina,” but many of them can be taken as a thoughtful and downright hostile commentary on the sectional cleavage. Charlie Daniels’ “Ragin’ Cajun,” for example, breaks out of jail to rescue his sister (in some far-off Northern town) from “the soul-destroying punk” that put a needle in her arm. Merle Haggard, who kicked off the genre back in the late 60s with “Okie from Muskogee” and “Fighting Side of Me” has not given up speaking for the rural South and West—despite being born m Bakersfield, California.

The most provocative country singer appears to be Hank Williams, Jr., whose “Country Folks Can Survive” is less Southern but more explicit than the rest. The song is an apocalyptic vision of a worn-out and sterile urban culture, in stark contrast with people who can still hunt, trap, and make their own wine. When the singer’s friend gets stabbed in New York for $27, he comments: “I’d like to spit some Beechnut in that dude’s eye/and shoot ’em with my 45.” Try to imagine what went through the audience’s mind when Mr. Williams insisted on singing it on the David Letterman Show.

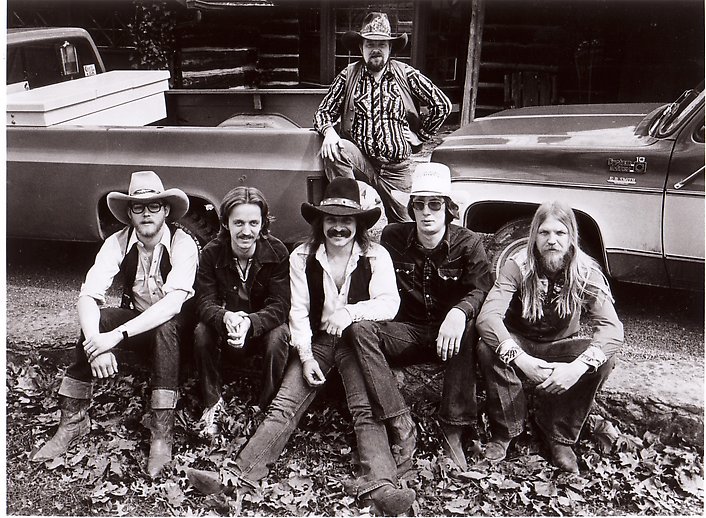

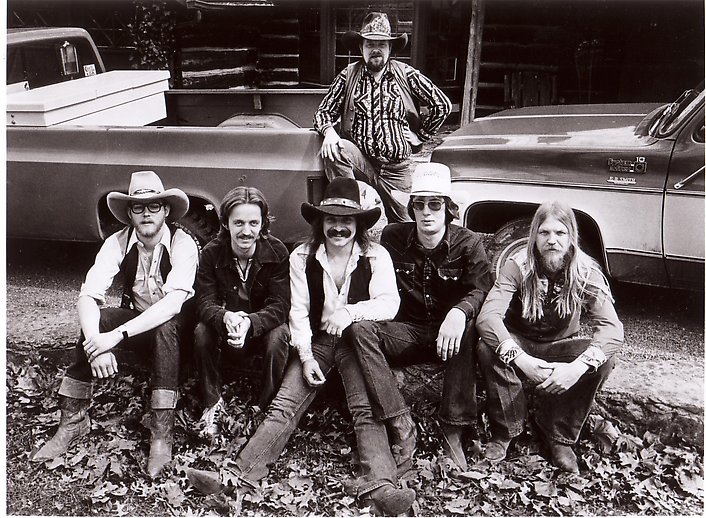

The song that best sums up the resurgent Southern feelings of a good many ordinary people is Charlie Daniels’ “The South’s Gonna Do It Again.” The song is, in fact, just a celebration of Southern Country-Rock groups like Lynnyrd Skinnyrd and the CDB, but the refrain is suggestive: “You can be loud and be proud/Cause the South’s Gonna Do it Again.” Do what? It is better that he does not say. But there are more than a few beer-swilling (or dope-smoking) rednecks, riding around in their pick-ups and listening to Charlie and Hank and Merle. Their discontent with the way things are is often expressed as complaints over high taxes, crooked politicians, and our gutless foreign policy, but their feelings run much deeper. These people once had a culture, a way of life (including an aristocracy) all their own. Now they are made to feel like exiles in the land their ancestors carved out of the wilderness.

These people are beginning to believe that the election of Ronald Reagan was not, in any sense, a revolution. Not only does the social and moral disintegration continue with no perceptible abatement, but even the much-heralded tax cut is being rolled back—with a special burden imposed on the Southern tobacco industry and on anyone rash enough to save his money. Even if prosperity were just around the corner, certain people have been heard to wonder—out loud—what difference it would make. America is already richer than Babylon and almost as moral as Sodom. It is not money our people crave, but life “and that abundantly.”

Of course, even rednecks give the Republicans their due: they are a lot smarter about money than the Democrats. Some Republicans arc under the delusion that the desire for money is the root of all goodness (read George Gilder and Michael Novak, if you won’t take my word for it). The real difference between the two parties is simply this: While Republicans know how to make money, the Democrats only know how to spend it.

Certain cynics on the right—people like Kevin Phillips and our own Samuel Francis—have been predicting an upsurge in conservative militancy, an activism born of despair. If increasing numbers of people become convinced that elections do not, cannot change things in the U.S., the discontented middle and working classes may well turn to more direct action, taking their cue from the tactics of other discontented groups: organize, demonstrate, and exert the sort of moral pressure no politician can resist— money and votes. If we can draw any conclusion from the evidence of country music, some Southerners, and, in fact, the plain folks of the whole country, are waking up to the fact that no one, but no one is going to lift a finger to help them, if they will not help themselves—not their own Jimmie Carter and not the well-meaning Ronald Reagan. If some sort of social revolution does take place in this country, it will not be made by discontented Chicanos, alienated radicals, or country club Republicans. It will come from the dispossessed ordinary Americans of the South, West, and Midwest. The plain Southern folks have more than once in the past demonstrated their ability to make trouble—in two revolutionary wars, for example—and they could be dangerous once more, if they ever decide just what it is the South is going to do again.

This article was originally printed in Southern Partisan magazine, Fall 1982.