Take up the White Man’s burden –

Ye dare not stoop to less –

Nor call too loud on Freedom

To cloak your weariness;

By all ye cry or whisper,

By all ye leave or do,

The silent, sullen peoples

Shall weigh your Gods and you…

– Rudyard Kipling, from The White Man’s Burden (1)

***

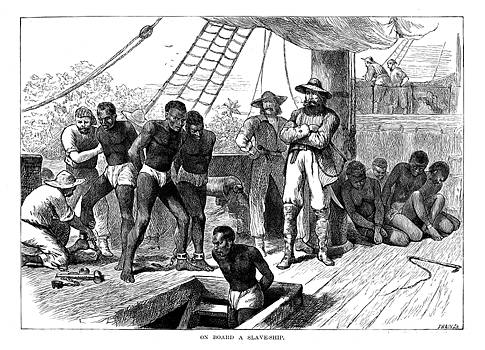

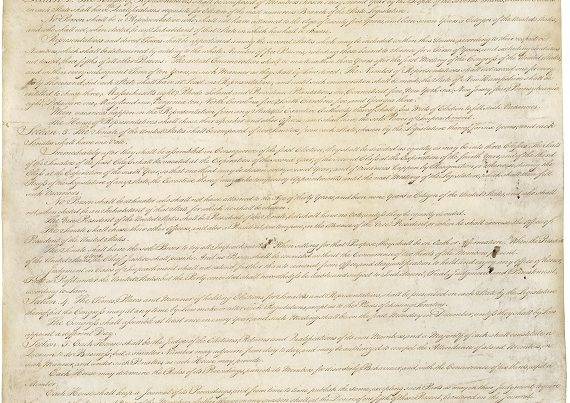

African slaves – purchased from African kings and slavers (2) – were first brought to the New World in1503 to the Island of Hispaniola. Eventually all the commercial nations of Europe were involved in the trade, and all their colonies in the Americas were supplied with them. Virginia received her first shipment from a Dutch Man-o’-War in 1619, but the carrying trade was left to Englishmen and to the illicit trade of the commercial colonies of New England. (3)

The pious “Puritan Fathers” of Massachusetts got into slavery early on with the enslavement of the Indians, but quickly got into the African slave-trade seventeen years after landing at Plymouth Rock. As The Rev. Robert Louis Dabney noted, “[I]t may be correctly said, that the commerce of New England was born of the slave trade; as its subsequent prosperity was largely founded upon it…” (4). Even after the trade was outlawed in the Constitution in 1808, New York, Boston, and Portland were the largest African slave trading ports in the world – doing illicit trading with Cuba and Brazil – when Lincoln took his oath of office (5).

As Dr. Dabney noted, “It is one of the strange freaks of history that this commonwealth, which was guiltless in this thing, and which always presented a steady protest against the enormity, should become, in spite of herself, the home of the largest number of African slaves found within any of the States, and thus, should be held up by Abolitionists as the representative of the ‘sin of slaveholding;’ while Massachusetts, which was, next to England, the pioneer and patroness of the slave trade, and chief criminal, having gained for her share the wages of iniquity instead of the persons of the victims, has arrogated to herself the post of chief accuser of Virginia…” (6)

But as John Randolph of Roanoke said, blood will tell in a four-mile heat (7). The “four-mile heat” was run in 1861-1865, and the blood of the Yankee and his altruism for the Black people showed itself in full relief…

Edward A. Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner during the war, reported:

The fact is indisputable, that in all the localities of the Confederacy where the enemy had obtained a foothold, the negroes had been reduced by mortality during the war to not more than one-half their previous number… In the winter of 1863-64, the Governor of Louisiana, in his official message, published to the world the appalling fact, that more negroes had perished in Louisiana from the cruelty and brutality of the public enemy than the combined number of white men, in both armies, from the casualties of war… The condition of the negroes at the various contraband camps in the Mississippi valley furnishes a terrible volume of human misery, which may someday be written in the frightful characters of truth. Congregated at these depots, without employment, deprived of the food to which they had been accustomed, and often without shelter or medical care, these helpless creatures perished, swept off by pestilence or the cruelties of the Yankees.

We may take from Northern sources some accounts of these contraband camps, to give the reader a passing picture of what the unhappy negroes had gained by what the Yankees called their ‘freedom.’ A letter to a Massachusetts paper said: – ‘There are, between Memphis and Natchez, not less than fifty thousand blacks, from among whom have been culled all able-bodied men for the military service. Thirty-five thousand of these, viz., those in camps between Helena and Natchez, are furnished the shelter of old tents and subsistence of cheap rations by the Government, but are in all other things in extreme destitution. Their clothing, in perhaps the case of a fourth of this number, is but one single worn and scanty garment. Many children are wrapped night and day in tattered blankets as their sole apparel. But few of all these people have had any change of raiment since, in midsummer or earlier, they came from the abandoned plantations of their masters. Multitudes of them have no beds or bedding – the clayey earth the resting place of women and babes through these stormy winter months. They live of necessity in extreme filthiness, and are afflicted with all fatal diseases. Medical attendance and supplies are very inadequate. They cannot, during the winter, be disposed to labor and self-support, and compensated labor cannot be procured for them in the camps. They cannot, in their present condition, survive the winter. It is my conviction that, unrelieved, the half of them will perish before the spring. Last winter, during the months of February, March and April, I buried, at Memphis alone, out of an average of about four thousand, twelve hundred of these people, or twelve a day’…

In all the war there had been no servile insurrection in the South – not a single instance of outbreak among the slaves – a conclusive evidence that the negro was not the enemy of his master, but, in his desertion of him, merely the victim of Yankee bribes. Assured, through a thousand channels, as these negroes were, that they were the victims of the most grinding and cruel injustice and oppression; assured of the active assistance of the largest armies of modern times, and of the countenance and sympathy of the rest of the world; assured that such an enterprise would not only be generous and heroic, but eminently successful, our enemies had heretofore failed to excite one solitary instance of insurrection, much less to bring on a servile war. It was thus that the war itself had greatly cleared up our moral atmosphere, and swept away much mist and darkness of doubt and delusion. After nearly three years of bloody struggle, we had at least already attained this result: the assurance that it was we, the Confederates, who had in charge the cause of freedom in the Western continent against the wild anarchy of ignorant mobs – we, who were saving civilization from the frenzy of democracy run mad – we, above all, who were guarding the helpless black race from utter annihilation at the hands of a greedy and bloody ‘philanthropy,’ which sought to deprive them of the care of human masters only that they might be abolished from the face of the earth, and leave the fields of labor clear for that free competition and demand-and-supply, which reduced even white workers to the lowest minimum of a miserable livelihood, and left the simple negro to compete, as best he could, with swarming and hungry millions of a more energetic race who were already eating one another’s heads off, and who regarded him and his claims as an intrusion and superfluity upon earth – to be retrenched and got rid of in the most summary manner… (8)

As Congressman Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr., of Minnesota, said of the true Yankee interest in the slaves and their emancipation:

Rather than assume the care of the slaves, they would control labor with the use of capital. It necessarily followed that, when the laborer ceased to be of service because of sickness or old age, he would be of no concern to capital. He could either get well or die without the capitalist being obliged to provide medical attention or bury the dead. Such was the interest that capital had in the result of the Civil War. (9)

Notes

- Kipling, Rudyard. “The White Man’s Burden” (1899). Rudyard Kipling’s Verse. Inclusive ed. (Garden City & New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1919) pg. 372.

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” Ed. Deborah G. Plant. (New York: Amistad/HarperCollins, 2018) pgs. 9-10, and Dust Tracks on a Road: An Autobiography. 2nd ed. (1942; Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1984) pg. 200.

- Dabney, Prof. Robert Lewis, D. D. A Defense of Virginia [And Through Her, of the South] in the Recent and Pending Contests against the Sectional Party. (New York: E. J. Hale & Son, 1867).Reprinted by Sprinkle Publications, Harrisonburg, VA, 1977, pgs. 27-31.

- Ibid. pgs. 33-41.

- “The Slave-Trade in New York,” editorial, Continental Monthly, January 1862, 87, in W. E. B. DuBois. The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America 1638-1870 (New York: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1896) pg. 179.

- Dabney, pg. 43.

- Bruce, William Cabell. John Randolph of Roanoke 1773-1833. 2 vols. (New York & London: The Knickerbocker P, 1922) II: 203.

- Pollard, Edward A. Southern History of the War. 2 vols. (New York: Charles B. Richardson, 1866) 2: 198-199, 201-202.

- Lindbergh, Charles A., Sr. Banking and Currency, and the Money Trust. (Washington: National Capital P, 1913) pp. 102-3, in John Remington Graham. Blood Money: The Civil War and the Federal Reserve. (Gretna: Pelican Publishing Co., 2012) pg. 5.

*