In talking about the Southern political tradition, it is most appropriate to point to the North Carolina Regulators and the Battle of Alamance Creek. This event was, in fact, only one of many such episodes in the colonial South–in the first 169 years of our history as Southerners before the first War of Independence.

There was Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia in 1676, which I recently learned to my delight one of my ancestors participated in. Just the next year the people of North Carolina ran out the officials in what is known as Culpeper’s Rebellion and for two years, had a government of our own choosing without any appointed officials and tax collectors from Britain. In 1719 the legislature and militia of South Carolina made the officials appointed by the Lord Proprietors flee in fear, never to return. There are other examples.

Alamance was the largest of all these events and the one immediately before the War of Independence. The old historians understood that these uprisings were precursors of the War of Independence when the colonists declared that governments must rest on the consent of the governed and can be justly overthrown if they do not.

As one of the old historians wrote of the Regulators:

“The boldness displayed by reformers opposed to royal authority provided a lesson in the use of armed resistance, which patriots employed a few years later in the American War for Independence.”

History is now perverted and you will hear such events as Alamance (and indeed everything about Southern history) interpreted according to Marxist class conflict theory. This is ludicrous, but it is what happens when your history is written by and presented to you by people who hate you, and regard the South as something alien to be destroyed. I don’t know what approach they take at the (Alamance) Historic Site, but knowing how much North Carolina Archives and History has been reconstructed by carpetbaggers in just the last few years, I am wary.

These rebellions all have the same outline in common. The people of a particular region, the neighbours and kinfolk who made up the society, had real grievances against government. They petitioned in an orderly way for relief and were ignored. Being free men, they then organised and acted to bring their grievances forcefully to the attention of the ruling powers. In most cases some of the participants paid a price with their lives, but in every case the powers were shaken up, discredited, and had to satisfy legitimate grievances.

They illustrate a point I would like to make about the Southern political tradition. Our basic Southern political instincts and assumptions differ from “Those People,” as General Lee always politely referred to the enemy.

The South, as M.E. Bradford wrote, was a thing that was “grown, not made.” The political philosophy long defended by Southern spokesmen rested on the implicit assumption that their society was a good thing, a product of the action of God acting through history. Therefore, government, merely a contrivance of man, should be the servant and not the master of society.

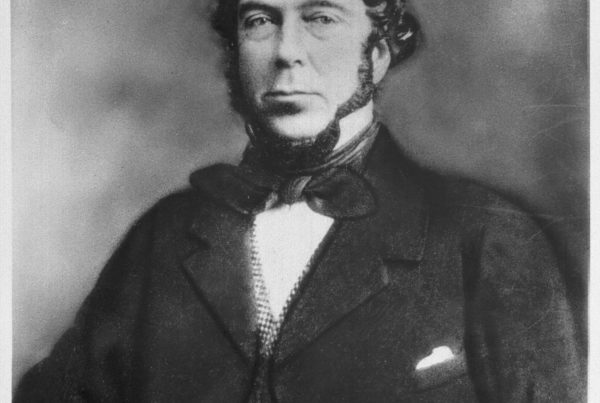

Robert Lewis Dabney, the brilliant theologian, made an address to the students at Davidson College just a year after The War. Most of the students were impoverished Confederate veterans making great sacrifices to continue their education—something that was typical of the South for the next half century. Dabney expresses what Bradford means. He calls his speech “The Duty of the Hour.” He advises the students that they should build and secure the family and thus save the living South even under defeat and evil occupation.

Dabney continues thus:

“Government is not the creator but the creature of human society. The government has no mission from God to make the community. On the contrary, the community is determined by Providence, where it is happily determined for us by far other causes than the meddling of governments—by historical causes in the distant past, by vital ideas, propagated by great individual minds—especially by the church and its doctrines. The only community’s which have had their characters manufactured for them by governments, like the Chinese and the Yankees, have had a villainously bad character. Noble races make their governments. Ignoble ones are made by them.”

John C. Calhoun had made the same point in his last testament, A DISQUISITION ON GOVERNMENT. And Calhoun was only putting into intellectual form what had been the starting assumption for Southern politics from the beginning. Society is natural, essential, and self-justifying, proceeding from man’s God-given nature as a social being. The legitimate purpose of government is to protect and preserve society. Thus, the Constitution should be the instrument of the people’s control of the government, and not of the government’s control of the people. This basic attitude could be seen at Alamance. It governed the War of American Independence, which was carried out and understood by our forefathers as the preservation of their natural “grown” society that was threatened by domination of a distant government of men that they could not hold responsible. This was the basic assumption that governed Jefferson and his successors in the United States government.

God, acting through history, made the Southern people. The U.S. government is a contrivance made by men. Our forefathers agreed to it because they regarded it as a way of protecting their people. When it becomes an enemy of society it has lost all claim on legitimacy.

One of my professorial colleagues, a classic example of Midwestern progressive, has a sub-teen son who was moved by the fears about the gasoline supply and the environment. He wrote to the President of the United States: “You should make everybody ride horses.”

Now conservation is a good thing, and horses are a good thing. But no Southerner who has a good idea automatically moves to wanting to use the government to make everybody else obey his good idea. Here is the difference between the South and America in a nutshell. It does not occur to a Southerner that he has a duty to correct other people. It would be presumptuous, unneighbourly, and, frankly, un-Christian. It does not occur to us that we have a divine right to stamp out the grapes of wrath wherever we think we see them.

But we are under the thumb of people whose life and identity is wrapped up in the notion that government should be our master and enforce their agenda. So our lives and our grandchildren’s future are being changed against our will in ways we do not like. “Those people” refuse to see the value of a Southern identity that is older than the United States. Their characteristic assumption is that America is a noble theory and righteous motives—as defined by themselves; that they must impose their theory, by force, to justify their claim to righteousness; that historical reality we know as the South has ever been a reproach to them that has to be destroyed.

Southerners are a stateless nation, a fact formally recognised by international geographers. Like the Welsh and the French Canadians until recently, our lives and our territory are in the power of people who do not represent our interests. It used to be that our state governments and our representatives in Congress to some degree represented us, but that is no longer true. Our representatives represent political parties, or banks, or special interests. They do not represent North Carolinians.

I refer you to the founding mission statement of the League. We declared that we were for the well-being and independence of the Southern people in every respect—political, economic, social, cultural.

That is a pretty revolutionary statement. We postulate that there is such a thing as a Southern people among all the myriad peoples of the earth, without reference to “American.” Even worse, we declare that we as a people have a right to determine our own fate.

We ought to frequently recur to that. We thought then that the noble and venerable thing known as the South was threatened. That is even more evident today. The powers that be in the United States are intent on disappearing us as a people. I am glad that the League is beginning to pay attention to what Southerners need to do in terms of economy. We are quickly becoming a minority in our own land that our ancestors claimed from the wilderness more than three hundred years ago.

What is the South? It is larger in territory and population than most of the independent countries of the earth. It has a distinctive history and long-lasting culture. It has been an important means of self-understanding for millions of people over many generations. Unlike “America,” which is an imagined thing in the notions of men, the South is a real thing—a society created to answer to our God-given human nature. Like a real living culture we can draw people to us and make them our own. During The War for Southern Independence every foreigner and Northerner who had lived in the South for any period of time identified with his people as a good Confederate. Need I mention General Pat Cleburne and our own outstanding North Carolina Chairman?

I know what I mean by a Southerner. I no longer know what an American is—it is a category empty of cultural and religious and historical content. An American is apparently anyone who claims to believe in democracy and is interested in making a buck. America is a business operation covered by dishonest platitudes. There is nothing wrong with a business operation, but the soul requires something more.

We are in one important way unlike most stateless peoples. We are more American than those who call themselves Americans who now rule us. We are the original Americans, the true Americans, so we may say that Americans have no power in what is now the empire called “American.” As a friend of mine puts it, the War for Southern Independence was a war between the Americans and the Yankees.

Our situation means that we will have to take care of ourselves. Our ancestors laboured and fought so that their posterity, us, could be free and prosperous. We must do the same for our posterity or see the South vanish forever. We have to accept that the institutions of our land are our enemies and create our own institutions. We have to be able to guarantee that nobody in the future will face loss of livelihood by being a Southerner. We have to guarantee that our culture and traditions continue to be part of the education of the young. We have to be militant about asserting and maintaining our speech, our manners, our customs, our traditional attitudes, our unique and admirable history. Change is inevitable in human society, but we still have the option to change in our direction not in theirs. In fact, the South is a living thing and it has thrived with dynamic change throughout its history without ceasing to be the South. It is a losing game for the South to try to be more “American” because America is moving so fast in the wrong direction that we could not keep up even if we wanted to.

This is a tall order. We operate under very different circumstances than our forebears who moved in a land still under development. We have to move in a highly-developed context. Armed resistance is not an option. It would be futile and counter-productive. But we can learn from our forebears’ spirit. We must obey the conqueror most of the time but we don’t have to accept his claims of legitimacy. We can abjure the realm, secede in spirit and in every other legal way we can. I think the dedication and the talent exists out there to keep Dixie vitally alive while “America” is dissolving.

There are costs to be paid, but we can minimize the costs with mutual support and clear goals.

Remember that the South always has been and is admired by many of the finest people beyond our borders. This confounds our enemies. The South is intrinsically admirable, a thing worth preserving for the benefit of ourselves, our posterity, and for the good of America and the world. Our enemies complain that people still love Dixie even though they have proved to their satisfaction that it is a bad thing. That is our great strength if we will build on it.