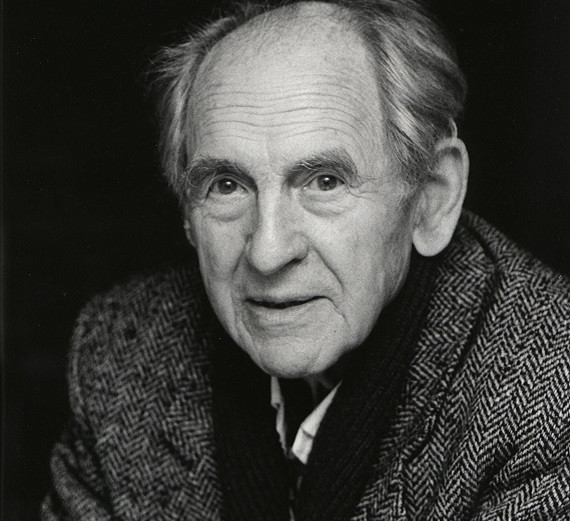

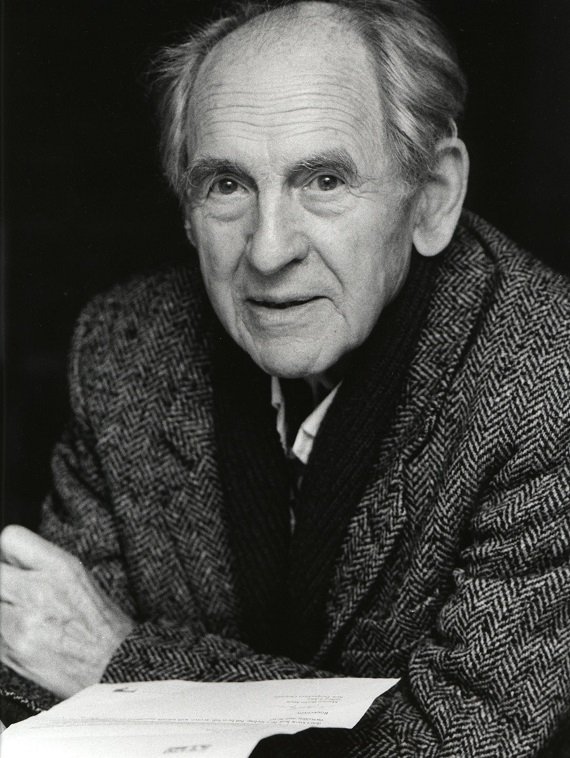

The time is ripe for a rediscovery of Leopold Kohr. Or perhaps better: the time is ripe for the discovery of Leopold Kohr, since few have any idea who he was. A select group of readers might connect him with E.F. Schumaker, author of Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered (orig. 1973). Kohr was one of Schumaker’s instructors, and the two remained lifelong associates and friends.

I.

Roughly three years after the Meltdown of 2008 I encountered an article online with the curious title, “This Economic Crisis is a “Crisis of Bigness.” It attracted my attention, because like many other observers I’d become convinced long before that both government and corporations had grown too large to accomplish even well-intentioned goals. The impulses for a more centralized society and a more economically integrated world — the impulses, that is, that bring about “bigness” — were mistakes from the get-go. Globalization promised universal prosperity, but instead has made the rich richer, slowly and painfully begun wiping out the American middle class, and created legions of unemployed or underemployed poor people — precariat is the term some writers are now using for this new class. The precariat consists of the army of adjunct faculty, temps, short-term contract workers, etc., most doing what they are doing because it is the only work they can find in the globalized “new economy.” The underemployment crisis heralds eventual civil unrest, especially with the Bureau of Labor Statistics insisting, against all experience, that the unemployment rate is just 5.5% (the U-3 figure as of this writing). Does anyone really think this is good, whether for workers or the economy at large?

The above article cited Leopold Kohr, on the grounds that he had predicted central aspects of the present situation over half a century ago in his magnum opus The Breakdown of Nations (1957). I immediately ordered Kohr’s book, and when it came, I put every spare minute into reading it straight through. It is not light reading. Works that raise fundamental issues in political philosophy as well as economics never are. I wondered why I’d never heard of Kohr or Breakdown before. Then I realized: unlike someone such as Joseph Schumpeter, whose analysis of the long-term fate of capitalism as an industrial system in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1947) was the most interesting I’d run across, Kohr was not at Harvard. He’d been exiled to lowly University of Puerto Rico. He was not part of the academic one percent.

Kohr had spent ten years, moreover, trying to find a publisher for Breakdown. This was no surprise, as the book’s basic premises, methodology, and conclusions ran 180 degrees counter to the then-reigning doctrines in all the fields he was addressing. Fascination with bigness gripped the social sciences. Large nation states were the primary visible actors on the global scene, and taken for granted as most were known quantities. Large corporations, likewise, were using new telecommunications technology to extend their reach. With the founding of the UN and the establishing of Bretton Woods, financial power had begun to migrate quietly to transnational organizations (e.g., the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, NATO, etc.). This, it was widely assumed by those at the levers of power, would continue until we had achieved a stable “new world order” in some sense of that term. The idea was not necessarily malicious in intent. It was presented as the culmination of a natural progression. Many of its advocates saw global unity as the best means of ending the dangers of high-level war, especially in light of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in light of the fact that newer nuclear weapons promised even more destructive force. These factors all worked against a manuscript like Kohr’s being taken seriously.

Breakdown was finally published in 1957, but was ignored completely and sank without a trace. It went out of print and remained out of print until 1978. A second edition, issued by a small press without fanfare, also disappeared despite the attention growth-related issues were receiving (courtesy of the Club of Rome’s The Limits to Growth). In 1986, we saw a repeat. The book was again out of print until Green Books reissued it in 2001. Its author had died in 1994.

Today, the situation is somewhat different. Widening wage gaps all over the world are one of the more conspicuous features of our times. Even globalist elites have expressed worry about them. High-level war is no longer perceived as the biggest danger civilization faces; the danger, now, is from populist groups and decentralized terror networks. Not to mention man-made climate change; if it is happening, it just illustrates the idea that systems (in this case, industrial civilization which burns fossil fuels for energy) cannot grow indefinitely without eventually disrupting surrounding systems and forcing them to reconfigure, very likely to our detriment. Thus we are seeing slightly less unanimity among thinking people on the fundamental benevolence of globalization and the possibility of endless economic growth. We have seen the formation of mega-states such as the European Union, but the supposed need for “austerity” measures is prompting rebellion in the voting booths in countries such as Greece, perhaps indicating that such entities are inherently unmanageable and doomed eventually to destabilize and collapse, just as the Soviet Union did. There are independence stirrings all over the world, from the Catalans wanting freedom from Spain, the Kurds wanting out of Iraq, the Chechens wanting freedom from Russia, Tibetans wanting independence from Beijing, and so on. Move to the U.S. Despite Americans’ “one nation under God,” equivalent movements exist in the South, Texas, Hawaii, Vermont, southwestern Oregon, and in doubtless in other states as well. In a sense, Leopold Kohr was their prophet.

Who was Kohr; and what, precisely, was his message?

II.

Leopold Kohr was born in 1909 in the small town of Oberndorf bei Salzberg, in Austria, where he grew up. He would retain fond memories of his hometown, which he came to see as governed efficiently and effectively. Oberndorf remained his regulative ideal for the proper size and reach of a political unit. An exceedingly bright youth, Kohr studied law at the University of Innsbruck and political science at the University of Vienna, obtaining doctorates in both subjects. Then he studied economics at the London School of Economics.

By now it was the 1930s. With the Spanish Civil War having broken out and the world inching toward the larger war to come, Kohr worked as a war correspondent where he befriended George Orwell, Ernest Hemingway and André Malraux. He observed with great interest the mostly self-contained separatist movements of Aragon and Catalonia within Spain, before returning to his native Austria. As a Jew, his stay there was short lived. He fled to the U.S. right before the Nazis annexed Austria, applied for, and received U.S. citizenship. His philosophical ideas forming rapidly, he began intensive work on what would become his major achievement: The Breakdown of Nations.

From the early 1940s until the mid-1950s Kohr taught economics and political philosophy at Rutgers University. During this period he struggled unsuccessfully to find a publisher for Breakdown. The manuscript — a treatise devoid of the charts, graphs, and equations that filled books and technical journals of mainstream social science — probably bewildered academic acquisitions editors. Was this economics or sociology? Or political philosophy? It was interdisciplinary, during an era when micro-specialization completely ruled academia (unless you were famous, like Schumpeter).

Moreover, as we noted, with its attack on the cult of bigness during a period of fascination with incipient global governance, Breakdown was swimming against a very strong tide. In the 1950s, almost no one knew what to make of Leopold Kohr. Without the assistance of British philosophical anarchist Herbert Read, the manuscript might not have found a publisher for many more years, if at all. Read persuaded British publisher Routledge & Kegan Paul to issue Breakdown, and Kohr’s major work came out in 1957. As we also noted, it met with complete indifference.

Kohr had accepted a position teaching economics at the University of Puerto Rico, and also advised local planners. The poor reception accorded Breakdown doesn’t seem to have fazed him, as he soon published a follow-up, The Overdeveloped Nations: The Diseconomies of Scale, in 1962. It also disappeared. In 1973, now 64, he moved to rural Wales, taught for a while at the University College of Wales Aberystwyth, lent his support to a Welsh independence movement, and published Development Without Aid: The Translucent Society (1976). He finally retired from teaching and began to divide his time between his Welsh residence and one near his beloved Austrian hometown. Meanwhile, E.F. Schumacher’s books Small Is Beautiful and A Guide for the Perplexed referenced Kohr’s ideas. This won them a small but significant audience. In 1983 Kohr received the Right Liveliness Award, a sort of alternative Nobel Prize, “for his early inspiration of the movement for a human scale.” He had planned on returning to Austria permanently at the time of his sudden death at the age of 84.

III.

What was Kohr’s central message?

We have stated part of it. It came to be expressed it in a few succinct phrases. “When something is wrong, something is too big.” And: “There seems to be only one cause behind all forms of social misery: bigness.”

In other words, the problem wasn’t this or that ideology, “left” or “right.” Both, Kohr would note, had served as the basis for cruel, totalitarian regimes. Nor is the problem this or that economic system. “Socialism doesn’t work,” say rightists; “capitalism is mired in contradictions,” say leftists. But either public or market-driven systems can be rendered workable under the right circumstances. These involve the human scale: the scale at which everyone in the community has a say in the choices and policies that affect them. In very large nation states, this can’t happen, voting and other pretenses of representation notwithstanding. Those at the top do not see those at the bottom, or even in the middle, as persons like themselves. States must therefore be kept small, so those voices can be heard — and, in particular, so that aggressive impulses can be contained.

Kohr called his key idea the power theory of aggression. Social brutality and cruelty appear and worsen to the extent the perpetrators realize they can get away with it. The problem is not their ideology but their becoming immune to retaliation. Those atop empires command vast authority structures including military might, along with the necessary resources, so that their victims have no realistic hope of mounting a response. “Everyone having the power,” Kohr says, “will in the end commit the appropriate atrocities” (Breakdown, p. 47). These include breaking their own laws if there is no greater power to hold them in check. That greater power can only be the aggregate will of the people, which can only operate as a kind of feedback loop if the human scale is maintained. When it is not maintained, those at the top, or in the middle, become ciphers. He who accumulates sufficient power in a political system grown too big “does whatever it induces in its possessor the belief that he cannot be checked by any existing larger accumulation of power” (ibid.).

Bigness thus corrupts nation states. Those at its center tend to accumulate more and more power, and to play faster and looser with whatever rules they began with, such as a Constitution. Eventually they will invade weaker neighbors, as Germany had done with Austria under the Nazis and the Soviets had done when they acquired Eastern Europe later. Then they become empires, whose rules know only aggression and force, whether against other nations or against their own people.

But under very large regimes, lines of authority become bureaucratic and unwieldy. They grow in complexity, often to correct for the unwieldiness. Bureaucracies tend to operate in ways that justify their own existence and expansion first, moreover. This frequently sends them not in search of solutions but manufactured problems that did not exist before. The entire system becomes less and less accountable, and there is a growing sense — even (or especially) under an immense totalitarian regime like the Soviet Union — that those in power literally do not know what they are doing. Ordinary Russians learned early in life not to depend on agents of the Soviet state; today, many U.S. citizens are figuring out the same thing.

Every kind of system, Kohr seemed to be saying, has an optimal size. If it exceeds that size, it experiences increasing dysfunction, be this turning against other systems or against its own.

Why, for example, would a 200-foot tall man (as in that cheesy 1950s sci-fi film The Amazing Colossal Man) be impossible? Because such a person would be crushed by the immense weight of his own skeletal structure, and a muscular system strong enough to hold him upright would just add to his enormous weight. Or consider cancer. While cancers differ, all are abnormal, chaotic, cell growths that disrupt their surroundings and eventually destroy the life of their host.

What is true of biological systems is true of political and economic ones. They have an optimal growth potential and size. If they get too big, problems grow and multiply. They attack their surroundings; and they start to self-destruct. There really are “limits to growth.” Some are imposed by their environment; others are inherent to the systems themselves.

IV.

But when Kohr was writing, wasn’t there a glaring exception to this: the United States of America? The “indispensable nation,” as neocons would begin calling it much later?

Following the Second World War, this seemed to be true, at least superficially. By the time Breakdown appeared, the U.S. had become the most powerful nation in the world, militarily and economically. But America seemed benevolent. Americans wore the white hats. We had been the good guys, and were viewed as such in Western Europe at least, where we had taken the lead in vanquishing Hitler.

Kohr was undeterred by this. Things would change for the “land of the free.” They had to, because the organic logic of bigness required it. In a chapter entitled “The American Empire” — Kohr might have been the first author to use those two words together — Kohr all but predicted the general trend of the next 70 years of U.S. history. Military might required a powerful central state to oversee it. Power always grows aggressive, and though it might take a generation or so, the U.S. would turn into everything it had once opposed. The Soviet Union had also emerged from World War II a much stronger entity. Kohr saw that the two superpowers were on collision course, and unless one or both collapsed from within, the result would be a third world war. As it turned out, we saw a frightening arms race, but no war because the Soviet Union collapsed. But Breakdown’s predictions for the U.S. came to pass!

Unlike previous empires, the Anglo-American world exercises economic rather than political domination, as City of London, Wall Street investment banks, and other leviathan corporations eventually had their political classes bought and paid for. Global corporations now reach around the world courtesy of so-called free trade agreements, the first of which was GATT in the late 1940s. The U.S. had actually begun to pursue an aggressive foreign policy to secure foreign holdings before Breakdown was published. Kohr apparently did not know that the CIA had already sabotaged the democratically elected government of Muhammed Mosadegh in Iran, so corporations could continue extracting that nation’s oil and taking the profits out of the country. At the end of his presidency, Dwight D. Eisenhower sounded the first public warnings about the “military-industrial complex.” It was probably already too late!

The U.S. would begin to pursue wars on false pretexts, such as in Southeast Asia in the 1960s. There were plenty of other instances, vastly smaller, in which democratically elected popular leaders were crushed by U.S. might when they stood up to corporate interests, as did (for example) Omar Torrijos in Panama. Officially, Torrijos died in a helicopter crash in 1981. Many Panamanians maintain he was assassinated.

Things have indeed gotten worse. When the Soviet empire collapsed, the U.S. war machine needed new enemies to fight. With the rise of neoconservatism which was essentially aggression concealed inside Straussian political philosophy, the 1990s saw a move towards initiating wars of choice for “regime change.” The government of Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega who assumed power after Torrijos’s death had been crushed by the first Bush regime in 1989. The following year saw the Gulf War which began an ongoing campaign of aggression against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Next came Kosovo, under the Clinton regime. Then, even more obviously, were Afghanistan and Iraq under the Bush II regime following 9/11. Those nations are now in shambles. One reason the U.S. empire could attack Iraq was the clear perception that Iraq had no real capacity to fight back. This perception was right. It took less than three weeks to bring the regime down and send Saddam into hiding. “Nation building,” however, proved to be impossible, costing roughly 4,500 Americans their lives, maiming thousands more, and rendering hundreds of thousands of Iraqis dead or homeless. It is no exaggeration to call the Iraq War a nearly-unprecedented military and public relations disaster for the U.S.

Or consider the rise of the domestic police state. It is common knowledge that the past several years have seen an explosion of deadly police violence against usually innocent people. If you live in the U.S., you are now more likely to be killed by a cop than by a criminal. Police are armed to the teeth with weaponry more suited to a battlefield, nearly all of it the product of the Department of Homeland Security. True to what Kohr would have said, police now act as if they are on a battlefield, with the civilian population the enemy. Explosions of aggression by a government against its own people also result from a size and scope of governmental entities that diminish accountability: police shoot innocent people because they usually get off with slaps on the wrist. If their department is sued successfully, taxpayers pick up the tab. What bullies and sociopaths can get away with, they will get away with! If there is no contrary power base to retaliate against the bullying, it will grow worse, as with a cancer. This, Kohr argues, is human nature. Only the balance of power that exists in small states where most everybody knows everybody else, and in a balance of power between small states, or other organizations (corporations, police departments, etc.), will we minimize the damage bullies and sociopaths are able to do.

Kohr’s predictions in Breakdown were spot on, in other words! Today, the U.S. federal government is widely regarded as the most aggressive entity in the world. We have gone from a state of affairs in which people fled the Soviet Union to the U.S. in search of freedom to one in which an Edward Snowden seeks asylum in Russia to be out of reach of what has become the world’s most aggressive power.

V.

Kohr’s thesis accounts nicely for other states of affairs. Consider North Korea, which illustrates very well the power theory of aggression. North Korea appears safe from attack, because they have nukes and a large and very well-disciplined military. The U.S. won’t threaten North Korea as it did Iraq. It is clear that anyone who invaded North Korea by conventional means would find themselves up to their necks in blood — their own. Anyone attacking using nukes would be retaliated against in kind. By the same token, the North Koreans are surrounded by governments with sufficient power (South Korea, Japan, China) that they don’t dare aggress! Thus the balance in that part of Asia. One unhappy result is that the sociopaths running North Korea turn viciously against their own on the slightest provocation. Theirs is easily the most repressive regime on the planet, where people disappear along with their families into prison camps for uttering even the slightest criticism of the government or belief in Christianity.

Or consider Iran. The war of words between the Iranian leadership and that of the West has continued for years over the former’s presumed nuclear program. The latest saber-rattling notwithstanding, it is likely that the U.S., probably alongside Israel, would have attacked Iran by now if both governments did not fear the repercussions: unlike Iraq, not only does Iran have the means to fight back conventionally (they could mine the Strait of Hormuz, for example), but the country has a sufficiently strong ties with both the Russians and the Chinese that an attack on Iran could lead to that third world war.

No one’s power elites, it seems, wish to preside over a radioactive wasteland!

Finally, it should be clear that Kohr was dead set against creating a European Union! He prophesied and promoted the division of Czechoslovakia into Slovakia and the Czech Republic, and the breakup of Yugoslavia into several smaller nations after Tito’s death. He continued to advise independence movements in Spain, Wales, and elsewhere for as long as he lived.

It is not hard to figure out what he would say to the new Greek government: send the EU packing! Forget making deals with the money titans in the euro zone. Default on their debt as their price for having made bad loans; leave the euro; establish your own currency; and begin the hard work of cleaning up the mess made by ever joining the euro-boondoggle! This course of action would, clearly, entail a very rough ride for the Greek people whose standard of living would probably drop further than it has. Investments would leave the country, a sign of disapproval by globalists. But if Greece persevered, self-determination could be her reward down the road! Plus, her having told the euro-crats to take a hike could destabilize the EU and lead to a stampede of other nations out, beginning with Italy and Spain. If that happened, the EU would unravel rapidly. What the Greek government does this year could determine the future of Europe: a return to autonomous nations, or continuance under the heels of a mega-state bureaucracy run by the money titans — who know that as Napoleon once put it, the borrower is always the slave of the lender.

Kohr’s thesis applies to more than just governments and mega-states, as the above example implies. If applied to corporate behemoths, e.g., leviathan banks, it predicts the increasing dysfunction to be found in those as well. It explains how such irresponsible practices as Enron “accounting” and mortgage “robo-signing” can get established. It explains how dangerous financial instruments such as derivatives can be invented, and how they can create a bubble capable of bringing down much of the world’s financial system. This is what happens when too many organizations not only grow too large but are networked together into a still-larger and more expansive system yet: today’s bloated edifice of global crony one-percenter capitalism.

Greed, bad political moves (e.g., the repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999), and short-term thinking precipitate increasing dysfunction, and from these we got the Meltdown of 2008! The bought-and-paid-for U.S. government rescued the leviathan banks instead of allowing them to tank. Too big to fail became the watchword of the day. Today, of course, these leviathans are still larger; the bubble on Wall Street is larger; the financial system is leveraged to the hilt; and none of the fundamentals have changed. This is why despite the present happy-talk about the U.S. “economic recovery,” many observers from various perspectives (Paul Craig Roberts, Peter Schiff, Doug Casey, Gerald Celente, Simon Black, and many others) are predicting a future meltdown that will make the last one look like a walk in the park by comparison!

VI.

Like Herbert Read his publishing benefactor, Kohr described himself as a philosophical anarchist. Anarchism denies that there can ever be either rational justification or moral legitimacy for the state, as a self-legitimizing monopolist of aggression. Well over 200 million people have been murdered by states just during the twentieth century. The philosophical anarchist eschews violent action as the appropriate response to the state, however. It is not just that such action typically leads to an even more violent response, but because violence is the way of the state, not a free people. Philosophical anarchists do not believe the state has any inherent right to command, or that any person has an obligation to obey, though of course it may be prudent to do so — especially if its agents have guns pointed at your head!

Kohr’s work thus has quixotic overtones he himself recognized. The shortest chapter in Breakdown follows “The Elimination of Great Powers: Can It Be Done?” with “Will It Be Done?” The text for this chapter consists of the single word, “No!” This is probably the shortest book chapter in the history of political ideas.

Kohr was therefore philosophical about the prospects his views had for a serious hearing, much less their being realized. Indeed, their impact has been limited to a relatively small counter-culture. There are things we can do, however. Kohr believed in local action out of a spirit of benevolence, working with people on the human scale to solve problems that the state arrogated for itself, the goal being to exhibit the state as redundant and irrelevant. The morality at work: one shouldn’t hurt people. At first, do no harm! One should help them, cheerfully, enabling their independence and freeing their minds from beliefs that encourage submission to the state and enable repressive state actions.

The philosophical anarchist’s regulative ideal is the self-governing community, a community small enough that everyone has at least some awareness of all others in the community as persons — extended families with children, the elderly, the disabled, and so on — so that those who are well off are aware of the plight of those who are not, or who have experienced a run of bad luck. The former will not see the latter as statistics.

What matters is not the economic arrangements but the scale. A “Kohrian” believes that if political units can be kept small, the good will that is natural within communities will serve the purposes reformers, social engineers, and technocrats have believed only the state could serve. The human scale, again, is the scale at which human beings can participate directly in the systems governing their lives. It alone makes room for both freedom and safety nets, because a human scale will give rise to safety nets through natural benevolence. Kohr would doubtless have approved of the “mini-states” cropping up around the world today.

VII.

Kohr was not saying the human scale would magically make aggressive impulses or bad behavior disappear. There would still be sociopaths around, just as there always had been. In small communities whose inhabitants grew up together and in which there is an organic sense of unity, persons become known quantities and sociopaths find themselves ostracized if not expelled when they prove they can’t be trusted. A few, perhaps, here and there, would successfully dissemble and scheme their way into power along with like-minded henchmen, forming rogue states. In a world of small states in which communities are not policed by some continent-wide political entity, this is unavoidable. But if political units remained small, the capacity of rogue states to do damage, e.g., by aggressing against their neighbors, would also remain small. Small self-governing communities would be aware what their neighbors are up to, and nothing prevents them from forming alliances of convenience. Even a sociopath knows that if he bullies the wrong person he’ll be slapped down hard. He would have a strong disincentive to invade. Whatever wars did happen in a world of small states would be small, affecting no one outside a limited region. Rogue states could be contained through alliances of convenience on the part of vigilant neighbors who got wind of what was going on. Wars capable of laying waste to entire continents (or the planet itself) are only possible between expansionist empires.

From one standpoint, Kohr’s view of this world is somewhat bleak. He doesn’t invoke the Christian concept of original sin as such, but he clearly sees human nature as having its dark side (it is interesting that religious references permeate Breakdown). Although we can learn to behave morally, morality is not the human default setting. Immoral behavior isn’t held in check by principle but by lack of opportunity, or perception of such. Kohr wasn’t promoting an ideology, “left” or “right.” In the hands of bigness, all ideologies are dangerous. He was one of those thinkers who wrestled seriously with what some of us consider the fundamental unsolved problem of political philosophy: how does society contain power? Or perhaps more clearly and specifically: how do those who wish to live free and stable lives in autonomous communities place checks on that minority among us whose entire value system revolves around dominating others: exercising power, whether politically or economically, and who see human beings as expendable pawns on a global chessboard?

There is the power of the sword, which exercises power directly by pointing a gun at your head. Then there is the power of the purse, which accumulates wealth, often through dishonest manipulations, then buys the loyalty of the man with the gun. The latter is probably a fair description of American crony capitalism, with its political class essentially owned by Wall Street and other lobbyists. Checking power means checking both powers, and the only means of doing is: shrink all organizations to minimize their reach, and then keep them small!

Sadly, like many social thinkers with a vision of “how things ought to be,” Kohr had no idea how to get from point A (where we are now) to point B (where we want to be, someday). No one was more aware of this than he, which was why he was philosophical about the prospects of his vision. He understood that the only way anarchism could work was if human beings were sufficiently ethical to respect each other’s personhood and space, and be able to check their emotions with reason. In the world of human nature as it is, that wouldn’t be likely except under relatively rare and temporary circumstances.

What then, are the prospects for the “Kohrian” vision? There both had been, and would be continue to be, periods when small states could prevail. In them, freedom would be possible for at least some. The U.S. in the 1800s offered this kind of circumstance for some, although obviously it wasn’t freedom for all. Blacks did not enjoy basic freedoms; nor did Native Americans. The former worked for and sometimes fought for at least some freedoms, but today, freedom for everyone has been compromised by the dominance of empire, which means centralization and the circumscribing of all lives, of whatever race or ethnicity, within sets of rules laid out in offices hundreds of miles away. Some of these draconian rules forbid children from opening lemonade stands, teenagers from shoveling snow, and adults from generating their own electricity off the grid. Freedom for persons has clearly grown narrower and narrower until it is barely exists outside our vocabulary. As the U.S. “deep state” expands, freedom shrinks even more!

VIII.

There is, however, light at the end of the tunnel! Kohr’s analysis predicts that no global “new world order” will prove sustainable. Any actual world state, or government of global scope — assuming it could be formed at all — would soon enter a period of increasingly abuse of those it had robbed of their autonomy. Much of the abuse these days would be financial. Then it would slowly strangle on its own bureaucracy, mismanagement, and corruption, possibly at a pace exceeding that of the ongoing decomposition of the EU.

One may consider first how poorly managed most federal agencies of the U.S. federal government are. Some cannot account for hundreds of millions of dollars. This is money simply lost! Imagine global equivalents attempting to oversee not a single oversized nation but several continents, managing continental divisions and further subordinate entities of increasing regionality and locality, taking their marching orders from increasingly distant Platonist philosopher-kings or Nietzschean supermen, or however the superelite at the very top will think of themselves.

The latter include, at most, a few hundred extended families. They can command financial resources most of us cannot imagine, get around quickly, but they cannot be everywhere at once! They will have instituted extensive authority structures which could be mapped on organizational charts. These would not manage themselves, however.

“New world order” authority structures would depend, absolutely, on the continued loyalty of functionaries and their administrators and undersecretaries further down the chain of command, who would need some autonomy to deal in a timely fashion with unanticipated regional matters or local “black swan” events. To function at all, therefore, a “new world order” would have to devolve some power out from Central Headquarters. If by some chance, its regional undersecretaries decided to begin accumulating and squirreling away resources for themselves, and those under them came to believe that their best opportunities were to support the regional undersecretaries whose agendas differed from that of the superelite at the top; and if this happened in multiple places at once, the “new world order” system would start to unravel. The elite would, perhaps, have a military at their disposal to put down regional rebellions — unless the undersecretaries had thought of that first and paid off a few regional generals. No “new world order” could survive without a huge and unified military machine. If the superelite lost control of even a part of it, the most likely result would be civil war and the disintegration of their empire, perhaps hastened by other forms of passive resistance already employed by ordinary people who reject being treated as statistical ciphers.

The fate of any “new world order” is speculation, of course. We have no hard evidence that the system dreamt of at Bilderberg meetings, perhaps, or behind the closed doors of the Trilateral Commission, is even possible. The closest the world has come is the EU, which should tell us something about the prognosis. While much of the public in most advanced nations is fairly oblivious, of course, captivated by sports, celebrity culture, and myriad other distractions, there are groups and a few regions that would refuse to cooperate. It is clear that efforts to disarm the public would meet with violent resistance in states like Texas and probably elsewhere. This is clear to those with a power elite mindset. Why, after all, does the U.S. Department of Homeland Security purchase ammunition, or shills for power such as the Southern Poverty Law Center keep lists of “hate groups” for mainstream media to demonize? While a few groups on such lists fit this bill, of course, many, if one actually studies them, have in common something far more dangerous to those with a power elite mindset: support for personal freedoms, the rule of law (not confused with rule by those in power), self-reliance, and community autonomy however they cash this out. They are suspicious of globalization and centralization, as they have not benefited. They have the means to make their views known before a wide audience. Call this the power of the pen (or, these days, of the bandwidth). It is conceivable that we will see an attempted power grab over the Internet during our lifetimes. It may work, but only for a time. Those who understand the technology will always figure out ways to get ahead of the bureaucrats. Control over the Internet will be short-lived at best.

Summarizing: empires subordinating continents may persist for a time, but Kohr’s analysis concludes that none will prove sustainable. The laws of systems posit that every system including units of governance has a maximum size it can sustain over time. Exceed that size, and the system enters a period of destructive aggression and unmanageable dysfunction. Usually it disintegrates from within, as did the Soviet Union. Then, once again, freedom and community autonomy become possible — for those who have made advance preparations!

IX.

I cannot recommend The Breakdown of Nations enough! I would recommend Leopold Kohr’s other works were they findable. Breakdown explains, more than any other single work available, why the U.S. has become an increasingly violent plutocracy, why so many of our institutions seem out of control — large corporations as well as government agencies — and why, even if we may be in for a rough ride in the near future, our long term future may be brighter than it may seem at present if we begin thinking about it and planning for it intelligently now!

Present-day institutions — governments, corporations, mega-states like the EU — are too big! They are unsustainable! Many of their activities are utterly irrational (e.g., the Iraq War, “austerity” that enriches banks while impoverishing peoples). Globalist entities created by a free trade mythos (be they the World Trade Organization or secretive agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership) that benefit primarily global corporations also consolidate too much power. Bigness and concentration enable greed, aggression, corruption, cruelty, poor judgment, dysfunction at all levels, and ecological destruction. Worse, it begets more bigness: organizations grow larger through desperate attempts to correct for, or at least manage, the corruption and dysfunction their present level of bigness has generated.

Leopold Kohr deserves far more attention than he has received, which aside from favorable citations from other outsiders like Schumacher, Kirkpatrick Sale, and a few others, is nearly zero. The present problem: today, if you are not on the bandwagons of globalization, urbanization, centralization, and unlimited economic growth, it is very difficult to get a seat at the table and be heard. But if people of whatever ideological inclination will track down The Breakdown of Nations and absorb its lessons, maybe we can start a new conversation, with Leopold Kohr finally coming into his own as what he was: one of the last century’s most original and insightful social thinkers.

“Leopold Kohr deserves far more attention than he has received, which aside from favorable citations from other outsiders like Schumacher, Kirkpatrick Sale, and a few others, is nearly zero. The present problem: today, if you are not on the bandwagons of globalization, urbanization, centralization, and unlimited economic growth, it is very difficult to get a seat at the table and be heard.”

It is incredibly sad but true.

Personally, I love this book and hold the author in great esteem. While it is true that I found his work through the more well known and less controversial E. F. Schumacher, I would like to think that if I had come across it even without Schumacher endorsement, I would have given it a read and loved its concepts and ideals just the same.