Russian-American relations over the past two and a half centuries, like the weather in Alaska, the land Russia sold to the United States in 1867 for ten dollars a square mile, have blown from very warm to extremely frigid; but its balmiest period by far was during the War Between the States. In stark contrast to America’s sixteen-year hiatus in diplomatic relations with Russia following the 1917 Revolution, the forty-four year Cold War with the Soviet Union after World War Two and the present discordant dialogues with the Russian Federation, Imperial Russia had maintained a close and cordial relationship with the United States from the moment the thirteen American colonies declared their independence from Great Britain in 1776. This, unfortunately, was not to be the case nearly a century later when the eleven Southern States declared their independence from the Union.

Although no foreign nation gave the Confederate States of America actual de jure recognition, both England and France actively engaged in a de facto relationship with the South by recognizing the Confederacy as a belligerent at the very beginning of the War, promoting the purchase of bonds issued by the Confederate government and, most importantly, permitting British and French weapons and other much needed war matériel to be shipped to the South aboard Confederate blockade runners, as well as allowing such vessels to be refueled and refitted in British ports like Bermuda and Nassau. Both nations also looked the other way while Confederate diplomats James Mason and John Slidell commissioned English and French naval yards to construct ships of war destined for the Confederate Navy. While most other nations remained far more neutral during the War, Imperial Russia under Tsar Alexander II was virtually an ally of the Union, and gave material military support to the United States.

Leading up to this rapprochement was Russia’s humbling defeat in the Crimean War in 1856 and the ensuing resentment toward its two major antagonists in that conflict, Great Britain and France, which matched that in the United States toward England. Not only had America fought two bloody wars with England in recent history, but in 1861 the Union was facing the grim prospect of Great Britain now forming an actual military alliance with the Confederacy. Such intervention would create both a massive second front all along the U. S.-Canadian border and a possibly unwinable war at sea with the powerful British Navy. While the United States was not a participant in the Crimean War, the Russian minister in Washington, Eduard de Stoecki, had informed his government that America might intervene on the side of Russia. This, of course, did not happen, but the American press and public certainly sided with Russia. President Franklin Pierce and the U. S. minister to Great Britain, and soon to be president, James Buchanan, on the other hand were initially pro-British, with Buchanan even referring to Tsar Alexander as the “Despot.”

England’s meddling in the United States during the Crimean War, however, particularly its active recruiting of American citizens for military service, turned the administration’s attitude toward Great Britain to one of hostility. This finally led to the expulsion of the British envoy, Sir John Crampton, as well as its consuls in Cincinnati, New York and Philadelphia, and much closer ties with Russia. Ironically, Crampton was named as Britain’s post-war minister to Russia. During that war, President Pierce, wishing to observe actual events on the battlefield, directed Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to send an official three-man military commission to St. Petersburg. The Commission was headed by Major Richard Delafield, who would be brevetted a major general in the War Between the States and placed in command of the harbor defenses of his native New York City. The Commission’s second in command was Major Alfred Mordecai, a Jewish West Point graduate from Warrenton, North Carolina, who was in command of the Washington Arsenal when he was sent to Russia. During the War Between the States, Mordecai refused to fight against either his native South or the Union, resigned his commission and went to Mexico to assist in the building of the Mexico-Pacific Rail Road. The junior member of the Commission was Captain George B. McClellan, later to rise to the rank of major general and be placed in command the entire Union Army in 1861.

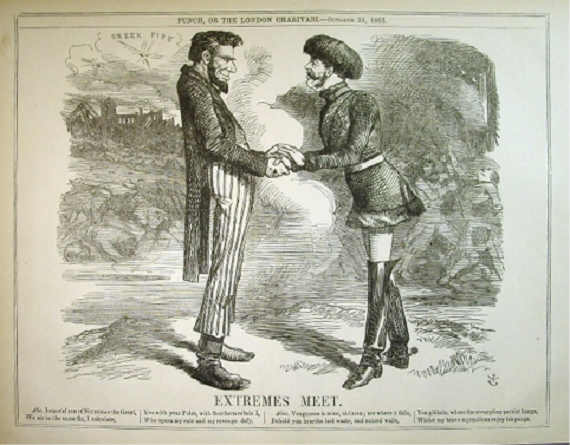

McClellan also developed close relationships with a number of the high-ranking Russians, including Navy Captain Nikolay Krabbe, who would become Russia’s Minister of the Navy during the War Between the States, and be directly involved in activities to deter British and French intervention. McClellan’s contacts also helped greatly in establishing the ties between Washington and St. Petersburg during the first years of the War. In early 1861, Tsar Alexander alerted President Lincoln about Emperor Napoleon III urging England to join him in forming an alliance with the Confederacy, an alliance Napoleon hoped would also include Russia. The following year, Russian Foreign Minister Gortchakov informed the U. S. charge d’affairs in St. Petersburg, Bayard Taylor, that Russia would oppose any intervention by England or France on behalf of the Confederacy. While English publications, such as the satirical magazine Punch, viciously characterized both Lincoln and Alexander as “bloody oppressors,” the British government feared what Russia might do if England intervened on the side of the South.

In spite of such fears, England was not only drawing up a blueprint for possible intervention, but actually began to lay the groundwork for it shortly after the opening shots of the War were fired in Charleston. Realizing that its military forces in Canada were too weak for either invasion or defense, the British War Office sent three thousand troops to Canada aboard the giant iron steamer “Great Eastern,” the world’s largest ship until the “Lusitania” was built in 1906, with preparations to ship an additional ten thousand on subsequent sailings. Work was also started to strengthen both the Bermuda and Nova Scotia fortifications. Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Palmerston directed the Admiralty to make plans for sending more than twenty warships to the western Atlantic for a possible bombardment of Boston and New York. Then, in November, the fires of a war that U. S. Secretary of State Seward said would “wrap the world in flames” came close to being ignited. While the Confederacy’s envoys to England and France, Mason and Slidell, were sailing to their posts aboard the British mail ship “Trent,” the vessel was stopped by the “USS San Jacinto” and the envoys detained. When threats of retaliation were issued by England and France, President Lincoln backed down and, without the requested apology, allowed the two envoys to continue on to Europe.

Meanwhile, in Russia, even though there was much press and oratorical support for the North, the Tsar’s government had not yet made any formal declaration concerning possible military action against England or France, or the forming of any official alliance with the Union in case of intervention by those countries. Russia made it abundantly clear through channels, however, that it would take strong action if there was any actual intervention in the War. One of the hints was the veiled threat posed by the Russian Army on the northern border of India, a territory that had only become an official part of the British Empire in 1858, and was still far too poorly garrisoned to counter any possible Russian military action. Another serious threat was economic, as Russia provided more than half of the thirty million tons of wheat consumed annually in England. If this source were to be suddenly curtailed, England would immediately face a catastrophic rise in bread prices . . . and a total cut off would lead to actual famine throughout the nation. This meant that Russian wheat was far more vital for Great Britain’s entire population than was Southern cotton for the nation’s textile mills.

Matters between England and the Union again reached a fever pitch in the spring of 1863, when there was grave apprehension over two large and powerful ironclad warships that were being built at England’s Laird shipyards, the same yards where the famed Southern raider “CSS Alabama” had been launched. All indications were that these strong vessels were intended for ultimate delivery to the Confederate Navy. This time it was the Union that considered starting a war by sending U. S. warships into English waters to destroy the two vessels. The crisis was finally averted in October, when the British government seized the ships for the Royal Navy. As these events were taking place, Great Britain was also planning a move to distract Russia from further support for the Union by instigating a revolt in Poland to overthrow Russian domination. It was finally decided, however, that such action would actually draw Russia and the Union even closer together . . . but the threat itself was sufficient to accomplish just what had been feared. England’s aborted Polish plot prompted Russia into taking a far more direct hand in the War and the Tsar ordered Navy Minister Krabbe to send the Russian fleets into American waters in both the Atlantic and Pacific. On September 24, six ships of the Baltic Fleet led by Rear Admiral Lesovskii aboard the frigate “Alexander Nevsky” arrived in New York harbor, and a month later seven ships of the Far East Fleet commanded by Rear Admiral Popov sailed into San Francisco Bay.

The commanders of both flotillas had orders from Minister Krabbe that in the case of any hostile moves taken by England or France against either Russia or the United States, their ships were to act as commerce raiders against British and French merchant vessels. The admirals were also ordered to place their ships under Union command in the event of actual war. As there were no significant U. S. naval forces in the Pacific, Admiral Popov of the Far East Fleet was further ordered to defend San Francisco against attacks by any Confederate raiders, such as the “CSS Shenandoah” which was wreaking havoc among American merchant and whaling ships throughout the Pacific. The Russian actions were met with wild enthusiasm in the North, and prompted U. S. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells to publicly say “God Bless the Russians.”

The close wartime relations between Russia and the United States continued for half a century after the hostilities ended in 1865. In that year, the two nations attempted an unsuccessful joint venture of massive proportions that would have established a telegraph line from Seattle to St. Petersburg . . . a line slated to pass through British Columbia, Alaska and Siberia. Two years later, Secretary of State Seward signed a check for over seven million dollars in gold to purchase Alaska’s almost seven hundred thousand square miles from Russia, the largest American land acquisition since the Louisiana Purchase in 1804. The sale, however was widely ridiculed in America at the time, with the press dubbing it “Seward’s Folly,” “Seward’s Icebox” and “Johnson’s Polar Bear Garden.” Many in the Senate also disliked the purchase, and the treaty was approved by just one vote. It was not until 1896, when gold was discovered in the Yukon, that the true value of Alaska’s riches began to be recognized. Sadly though, some of the hoped for riches turned out to be mere fool’s gold for most of the hundred thousand prospectors who made the arduous trek to the Klondike. While a few did find golden wealth there, the vast majority found little or nothing.

In what might be deemed a bit of poetic justice for the South, there were also problems for Russia in relation to the agreement. There was a popular Russian myth that the seven million dollars in actual gold had been lost when the ship carrying it to St. Petersburg sank in the Baltic Sea. It was indeed a fact, however, that little if any of America’s Alaskan payment ever found its way into the Tsar’s treasury. The actual cause for this was that after the funds had been duly deposited in European banks, most of the money was then transferred to accounts of various companies controlled by Tsar Alexander’s younger brother, Grand Duke Contantin, the man who, in 1857, had initially proposed selling Alaska to the United States.

In view of all this, perhaps the Democrats in the 36th Congress should have called for the appointment of a special prosecutor to investigate if there was any collusion between the Russian government and Lincoln’s presidential campaign, or if there was any vote tampering by Russian operatives that could have stolen the 1860 election for the Republican ticket.