In June 1863, Fitzgerald Ross, a British military man who was collecting information about the war in America, paid a visit to Richmond, Virginia, the capital city of the Confederacy. There he met with some high officials of the government, one of whom was Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin. Ross described their meeting his 1865 book A Visit to the Cities and Camps of the Confederate States:

We had a long, and, I need hardly say, a most interesting conversation. We talked about the war and the foreign prospects of the Confederacy, and the atrocities which the Yankees seem to delight in committing whenever they have a chance.

“If they had behaved differently,” Mr. Benjamin remarked—“if they had come against us observing strict discipline, protecting women and children, respecting private property, and proclaiming as their only object the putting down of armed resistance to the Federal Government, we should have found it perhaps more difficult to prevail against them. But they could not help showing their cruelty and rapacity; they could not dissemble their true nature, which is the real cause of this war. If they had been capable of acting otherwise, they would not have been Yankees, and we should never have quarreled with them.”

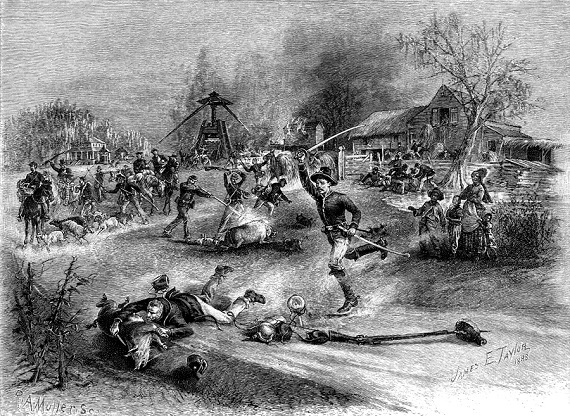

The policy of total war adopted by the North was indeed cruel and rapacious, and some of my books document this fact. A few years ago, I began editing another account that offered further evidence of such barbarism: the memoir of Cecilia Lawton, the daughter of a Georgia plantation owner. During the war she married a South Carolina planter and went to live at his plantation in Beaufort District, but a few months later, she found herself fleeing from the army of General William T. Sherman as it burned and plundered its way through the state. While her husband served in the Confederate Army, Cecilia made her way back to Georgia, and, as she traveled with two other ladies to Savannah, she witnessed the aftermath of the brutal “March to the Sea” through that state, witnessing many scenes of cruelty and horror, much of it having to do with animals. She observed:

Not a living animal—horse, cow, sheep, goat, hog, or even chicken—was seen on the entire route, but hundreds, yea, thousands, were seen lying dead and rotting on the roadside and in adjacent fields, for it was Sherman’s policy to have all such killed that could not be taken with his army to Savannah …

We found two “slaughter pens” of dead horses, where hundreds of decaying animals gave out noisome and putrefying odors extending for one or two miles in every direction! We could scarcely endure to breathe the air, and learned that the few inhabitants who were still living near these unfortunate localities had been obliged to fly from the pestilential odors. One of these pens was a country graveyard, and adjoining a neat little church! It seems too monstrous to believe, but I am writing only of what I saw myself.

These inhuman Yankees had driven herd after herd of horses & mules into the graveyard, shooting them by scores, until they were piled one upon another, entirely filling the small enclosure and covering the sacred graves of their dead fellow men!

In her book Through the Heart of Dixie, Anne Sarah Rubin recounted several incidents of the mass killings of horses in Georgia by Sherman’s soldiers. J. A. McMichael, a resident of Butts County, reported that Federal soldiers slaughtered about a thousand horses taken from citizens and left the carcasses on an island in the Ocmulgee River. Another story is connected with the Little Ogeechee Church near Oliver, Ga. Here, in the church graveyard, General Sherman had reportedly penned some five hundred white horses which he intended to take to Savannah, but then decided they were not worth the trouble, and ordered them shot. Even into the 20th century, local residents recalled finding bullets embedded in some of the headstones. This church cemetery is likely one of the “slaughter pens” that Cecilia Lawton saw. One of Sherman’s officers, George W. Nichols, stated that on December 6, 1864, the army had been concentrated at the “Ogeechee Church” for two days.[1]

In another incident, Union officer Smith D. Atkins recorded in his memoir that a cavalry brigade of his army had “captured hundreds of horses” in November 1864 after departing from Milledgeville. “The captured animals were a great incumbrance,” he added, “and after each trooper had secured a good mount, over five hundred horses were killed by the Second Brigade.”

In his book Starving the South, Andrew F. Smith noted that the northern army was thorough in its destruction of the Georgia countryside. “While reports vary on the amount of provisions confiscated or destroyed by Sherman’s army, best estimates include 10,000 horses and mules, 13,000 cattle, half a million tons of fodder, and 13 million tons of corn, plus untold numbers of hogs, sheep, chickens, and vast quantities of sweet potatoes and other produce.” Smith quoted one of Sherman’s soldiers as saying, “I think a katydid, following our rear, would starve.”

At the end of the war, when Cecilia and her husband returned to his plantation in Beaufort District, they found that their house had been reduced to a heap of ashes and seven chimneys. They tried to survive here, enduring many hardships and dangers, but later moved to James Island near Charleston, where her husband had been born and raised. After many years, and after much hard work and numerous setbacks, the couple prospered, so much so that Cecilia eventually became the proprietor of the Mills House hotel in Charleston, which she renamed the St. John Hotel. Sometime in the late 1870s or thereafter, she wrote a memoir that covered all her experiences from her childhood up into the years of the carpetbagger regime in South Carolina.

Parts of her memoir were utilized by Clyde Bresee in his How Grand a Flame (1996) and Sea Island Yankee (1982), but it has never been published in full until now—and it is now available under the title that she gave it, Incidents in the Life of Cecilia Lawton. This book allows Cecilia to present her experiences in full, and in her own words. In his preface, Dr. James Everette Kibler sums up her story well: “What one may take away from Mrs. Lawton’s narrative is the record of a strong and resilient couple forced to endure the horrific conditions imposed by war, invasion, and a brutal conquest.”

[1] Nichols, The Story of the Great March, 81.