One of the most interesting research interests for me is exploring the connections between Poles and the American South. Research-wise, this is undoubtedly a niche area and, despite everything, under-researched, primarily due to the difficulty in accessing sources: letters, notes, and diaries. This niche topic of Polish-American history, however, seems so fascinating that it constitutes a treasure trove of mysteries. Polish connections with the American South primarily concern the period of the War Between the States. Researchers who have made significant progress in this area include Piotr Derengowski, Łukasz Niewiński, and Mark F. Bielski. By portraying Poles in the American Civil War, for example Derengowski, consolidates the stories of various figures to a certain extent and exhausts the topic in an exceptionally comprehensive monograph.

Derengowski rightly notes that (aside from his own research), the only source to draw on is Mieczysław Haiman’s work titled “Historja udziału Polaków w amerykańskiej wojnie domowej” (The History of Poles’ participation in the American Civil War), published in Chicago in 1928.[1] However, as Derengowski notes, this work is fraught with errors and myths. The participation of Poles in the Union forces is much better documented, primarily because more documents have survived and, admittedly, a significantly larger group of Poles served in the Yankee army. The number of Poles in this army, however, was not due to any tendency to idealize the North. This disparity was simply due to the distribution of Polish emigrants in the United States at the time. Exact numbers are not, and likely never will be, known. Derengowski suggests, however, that at the outbreak of the conflict, the Polish force was sufficient to form several regiments and even a brigade.[2] Other historians like Bogdan Grzeloński and Izabella Rusinowa state that “the total number of refugees from the 1830-1831 uprising and the Spring of Nations can be estimated at about 2,000.[3]

For every researcher, however, the participation of Poles in the Confederate Army is of great interest. The greatest value of this research lies in the Poles’ motivations to side with the South. What motivated them? Why did they support the South? Since many historians, while ignoring inconvenient facts, strive to reduce the Southern cause solely to slavery, the participation of Poles in the Confederate States of America must be of significant historical and research importance here. Certainly, the Poles’ motivations cannot be reduced to the defense of slavery. The circumstances that pushed Poles to participate in the war on the side of the South stemmed from factors of so-called political emigration.[4] In most cases, their motivation was a specific concept of freedom.

This concept is outlined quite precisely by Mark F. Bielski:

…The attitudes and ideals that motivated these Poles who participated in the American Civil War developed over generations prior to their arrival in the United States. Many brought with them a military tradition, a zest for freedom and a will to defend liberty. The concept of defense would have been inherent in Poles who would take up arms since they had emigrated from a country that in the 18th century had disintegrated and had come to be dominated by external powers. Whether peasant or gentry, they would have seen their liberties eroded as foreign systems of government, and often armies, replaced most opportunities for self-determination”.[5]

In most cases, Poles were indeed driven by anti-imperial motives. These were the decisive factor in Poles realizing their values by participating in other conflicts whose causes seemed close to their hearts. In the case of the South, Poles participating in the Confederate army undoubtedly viewed the federal government as a tyrant and dictator who had attacked the South (this is confirmed, for example, by the writings of Gaspar Tochman). The causes of the South and Poland seemed similar. As Gracjan Kraszewski writes:

…For the South, like Poland, was also being unjustly denied its right to national self-determination by tyrranical oppression (the Russian czar Poland’s own Lincoln,…).[6]

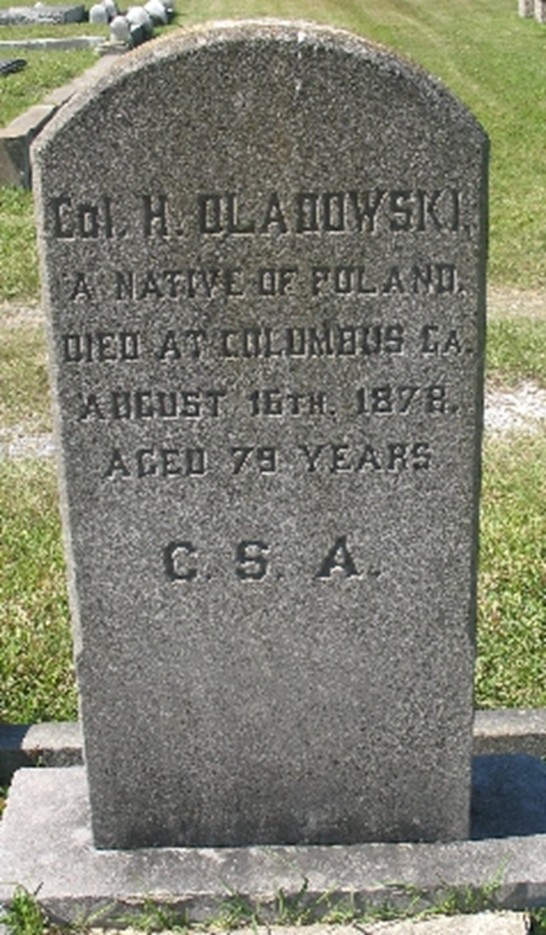

August 16th marked another anniversary of the death of Hipolit Oladowski, perhaps one of the most forgotten and least researched Poles who fought in the war on the side of the South. Unfortunately, Bielski’s fascinating work makes no mention of Oladowski. Derengowski, however, touches on his life, noting that many unknowns remain.[7] Oladowski’s birthplace seems problematic. He was born in 1798. American records list a name that is difficult to decipher, though it most likely refers to the village of Mniszew in the Masovian Voivodeship (currently in a region administratively governed by the capital of Poland, Warsaw).

Oladowski’s significance seems to be particularly meaningful, as he was the only Pole to serve as head of General Braxton Bragg’s armament service. Oladowski was said to have held the position of armorer throughout the war. His biography seems equally significant. According to some sources, he initially served in the Tsarist (Russian) army, from which he deserted and joined the November Uprising (1830-1831) in 1830, a Polish uprising against the Tsarist occupation. The uprising ended in failure, and Oladowski, along with other officers and insurgents, was sent to Siberia for life. He managed to escape Siberia and eventually made his way to the United States. Derengowski notes that Oladowski’s experience immediately secured him a position in the army’s Armament Department.[8]

Oladowski was assigned to manage the arsenal in Baton Rouge. In February 1861, he became the chief arsenal manager for the Louisiana State Army. He was quickly assigned to General Bragg’s ordnance staff. In March 1861, the Confederate Congress promoted Oladowski to the rank of captain of artillery. Oladowski managed the entire arsenal quite efficiently throughout the war and performed his assigned duties diligently. He was excellent at checking and monitoring the wear and tear of the weapons arsenal. He also provided recommendations on how to properly handle weapons so as not to waste them. The friendship that developed between Oladowski and Bragg seemed to be so sincere and lasting that after the war, Bragg, who was working on the expansion of the port in Mobile, offered Oladowski a job. By taking on local community activities, Oladowski participated in the restoration of the South, which led him to consider the South his second homeland. He remained in America until his death. Unfortunately, no photo of Oladowski has survived. Oladowski died on August 16, 1878, in Columbus, Georgia. He is buried in Mobile, Alabama, at Magnolia Cemetery.

Finally, we must consider the necessary reflection: it is worth remembering this Pole and others who, unable to come to terms with the loss of their homeland, attempted to utilize their skills in the fight for the independence of the South. However, the choices of many of them to side with the South, as historians Grzeloński and Rusinowa note, prevented their biographies from entering national hagiography.[9] They were, in a sense, condemned, just as the South was unjustly condemned. The situation was different for those Poles who supported or served in the army of the North. These, in turn, like “brevet general” Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski, for example, have their places in Arlington National Cemetery. Bielski rightly concludes that among Poles: „some were officers, some were enlisted men. Many were first generation immigrants, but some were second generation. While the majority served the North, some served the South, although most of those were also opponents of slavery. One of the main reasons for this rather odd situation was the fact that Russia was the only major European power to support the North”[10].

**************************************************

[1] P. Derengowski, Polacy w wojnie secesyjnej 1861-1865, Wydawnictwo Napoleon V, Oświęcim 2015, p. 9.

[2] Ibidem, p. 410.

[3] See: B. Grzeloński, I. Rusinowa, Polacy w wojnach amerykańskich 1775-1783, 1861-1865, Wydawnictwo MON 1973, p. 149.

[4] P. Derengowski, op.cit., p. 393.

[5] M.F. Bielski, Sons of the White Eagle in the American Civil War: Divided Poles in a Divided Nation, Casemate Publishers, Philadelphia & Oxford 2016, p. 10.

[6] G. Kraszewski, Catholic Confederates: Faith and Duty in the Civil War South, The Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 2020, p. 126.

[7] Derengowski, op. cit., p. 534.

[8] Ibidem, p. 536.

[9] See: B. Grzeloński, I. Rusinowa, op.cit., p. 185.

[10] M.F. Bielski, op.cit., p. xi.

Bibliography

Bielski M.F., Sons of the White Eagle in the American Civil War: Divided Poles in a Divided Nation, Casemate Publishers, Philadelphia & Oxford 2016,

Derengowski P., Polacy w wojnie secesyjnej 1861-1865, Wydawnictwo Napoleon V, Oświęcim 2015,

Grzeloński B., Rusinowa I., Polacy w wojnach amerykańskich 1775-1783, 1861-1865, Wydawnictwo MON 1973,

Kraszewski G., Catholic Confederates: Faith and Duty in the Civil War South, The Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 2020.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

Nice piece! Thank you. Glad to hear the Poles were represented, especially since three of my favorite human beings were/ are Polish: Chopin, of course; Joseph Conrad; and my one-year-old grandson, whose lovely mother is part Polish.

“Abe: Imperial son of Nicholas the Great, We air in the same fix I calculate, You with your Poles, with Southern rebels I, Who spurn my rule and my revenge defy.

Alex: Vengeance is mine, old man; see where it falls, Behold your hearths laid waste, and ruined walls, Your gibbets, where the struggling patriot hangs, Whilst my brave myrmidons enjoy his pangs.

Abe: I’ll show you a considerable some Of devastated hearth and ravaged home; Now less about the gallows could I say, Were hanging not a game both sides would play.

Alex: Wrath on revolted Poland’s sons I wreak, And daughters too; beneath my knout they shriek. See how from blazing halls the maiden flies, And faithful Cossacks grasp the screaming prize.

Abe: In Tennessee I guess we’ve matched them scenes, And may compare with Warsaw New Orleans. The Vistula may bear a purple hue; As deep a stain has darkened the Yazoo.

Alex: When my glad eye the telegram enjoys Of women whipped, and soldiers shooting boys, I praise De Berg to supplication deaf, And glorify severe Mouravieff.”–Punch Magazine 1863