Tennessee Johnson, DVD, directed by William Dieterle (1942; Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Home Entertainment, 2020).

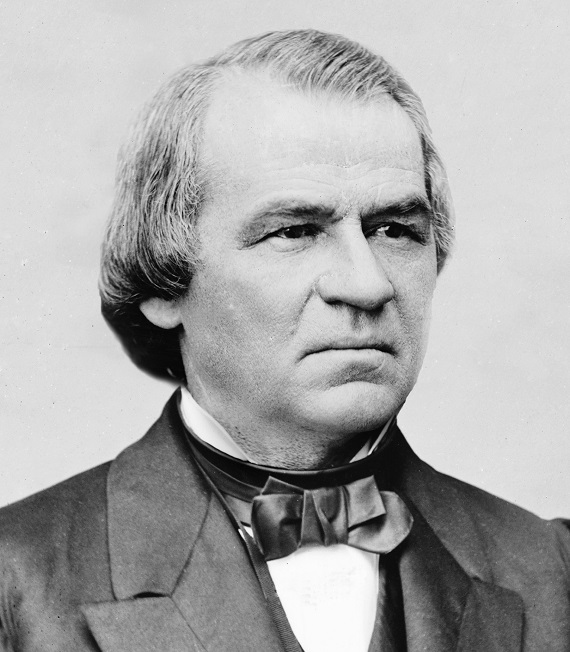

In the golden age of Hollywood, biographical dramas were a big draw at the box office. One that was not, however, was Tennessee Johnson, based on the life of Andrew Johnson, the 17th President of the United States. These movies took some liberties with the facts to create and entertaining story and Tennessee Johnson was no exception to that rule. However, it made some points which are worth noting.

Tennessee Johnson was released in 1942, which was during World War II. It was obviously an effort to support national unity, which was prevalent during that war. It starred Van Heflin as President Andrew Johnson, Ruth Hussey as his wife and First Lady Eliza Johnson, Lynne Carver as their daughter Martha Johnson Patterson, and Lionel Barrymore as Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Johnson’s political nemesis. Ruth Hussey portrayed a supportive and dutiful wife, which is refreshing to see in this age of feminist propaganda. Though the part of the movie dealing with the War Between the States is very pro-Union, the part dealing with Reconstruction is quite pro-Southern relative to that. It is a very good movie about Reconstruction, and there are not many of them.

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina and his father died when he was three. His mother remarried and his stepfather had him apprenticed to a tailor. Johnson ran away heading west and the movie opens when he arrives in Greenville, Tennessee. He becomes a tailor there and starts making leveling speeches. In the movie, this leads him to become sheriff, assemblyman, congressman, governor, and then US senator. In actuality, he was elected town alderman, mayor, state representative, state senator, presidential elector, congressman, governor, and US senator. When secession came in 1861, Johnson, although a Southern Democrat, remained in the US Senate after Tennessee seceded and supported the Union. He is depicted as campaigning for the Democrats and against Lincoln in the 1860 election campaign, although speaking out against secession. Then he is depicted after the election as urging the Southern senators to remain in the Union in order to block Lincoln’s policies and to work to defeat him in 1864. While the Southern states actually seceded one by one, their senators are depicted in the movie as all leaving at once. Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi delivers an address before the Southern senators leave. He was played by Morris Ankrum, who gave a very sympathetic portrayal. As the Southerners leave the Senate chamber, the song “The Vacant Chair” plays in the background. This was a song of the War Between the States about a family who lost a son in the war. A clip of that scene follows:

Johnson stayed in the Senate until March 1862 when he was made Union military governor of Tennessee with a commission as brigadier general. His headquarters were in Nashville, which had fallen by this time and remained under Union control until the end of the war. In the movie, he goes to Lincoln to offer his military services immediately after the Southern senators leave, although the war had not started yet by that time. He is then depicted as winning a fictitious battle in November 1862 which never took place whereby the Confederates attack Nashville demanding its surrender and Johnson’s forces defeat them.

The movie’s next scene takes the viewer to the 1864 Union Party Convention in Baltimore. The Union Party that year was an alliance of the Republicans and the War Democrats. Lincoln selected Johnson, a War Democrat, as his running mate to unite the two factions. The next scene begins the story in earnest when an emissary of Lincoln, portrayed by Russell Hicks, calls on the leaders of the Republican delegation at the convention. They are headed by Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, portrayed by Lionel Barrymore. His role in this part is very similar to that of his role as Mr. Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life four years later, wheelchair and all. However, Stevens was never in a wheelchair. He was born with a club foot which caused him to have to walk with a cane and he was carried about in a chair during the last years of his life. He is depicted in the movie as carrying a cane with him in his wheelchair, though never using it. The emissary praises Stevens’ opposition to slavery, but disagrees with his plans of retribution on the South after the war. The emissary says that Lincoln opposed retribution and supported reconciliation. Stevens is talked into supporting Johnson, though he does so grudgingly. Stevens is depicted as saying to the emissary, “Oh, Johnson is a loyal man, but, as a Southerner, he’d be bound after the war to stop our vengeance on the South.” At the close of the scene, after everyone else leaves, Stevens complains concerning Johnson, “A mudsill tailor from the heart of rebel land, the next vice president of the United States.” Mudsills were the lowest class of whites and this term is used quite a bit in the early part of the movie.

After the surrender of General Robert E. Lee, a scene of the victory celebration in the streets of Washington on the night of April 14, 1865 is depicted. “The Battle Cry of Freedom” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” are played by a band and cheering crowds are waving 48-star US flags and carrying pro-Union signs. The flag had 48 stars in 1942, the year the movie was made, but it had 35 stars on the night depicted in the scene. Perhaps that was to show support for the war effort in World War II. A crowd appears at Johnson’s window calling for him. When Johnson comes out, one man yells, “Hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree.” Then another man yells, “Hang Lee, too.” Johnson tells the crowd to go to the White House and serenade the President, “but don’t grieve him with shouts about hanging our fellow countrymen.” One man says that they just came from there and that he had gone to Ford’s Theater. With that, Johnson addresses the crowd saying, “The few words I shall say to you are not my own. ‘With malice toward none, with charity for all, let us bind up the nation’s wounds.’ And General Grant, when he took Lee’s army, there was no pride, no boasting, he just said, ‘Let us have peace.’” Grant actually said that three years later when he accepted the Republican Presidential nomination. That night, of course, Lincoln was shot and he died the next morning, resulting in Johnson becoming President.

With the death of Lincoln, two opposing policies of Reconstruction clashed: that of reconciliation desired by Lincoln and which continued to be carried out by Johnson, and that of vengeance by the Radical Republicans led by Stevens. The clash of these views is depicted in a scene at the White House. Stevens is depicted as saying to Johnson in a meeting of the President with Congressional Republicans, “I propose that we treat the South as an outside, conquered people, that we confiscate all estates worth $10,000 and containing 200 acres. Then, sir, I would give every adult colored man 40 acres of land, sell the rest and pay for the war with it.” Johnson is then depicted as replying, “So it comes to this. You fought a war to preserve the Union. Having preserved it, now you deny that it exists. Gentlemen, my aim is to carry out Lincoln’s policies.” The real President pro tempore of the Senate at the time was Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, but the character in the movie depicted in that office is Senator Jim Waters, portrayed by Charles Dingle. Waters then replies, “Try to get into your head that Lincoln’s Reconstruction policies died with him.” Johnson replies, “Lincoln always held that the Confederate States could not secede, that they were, therefore, never out of the Union. Now they stopped the fighting, they took the oath of allegiance to the United States, they ratified the amendment abolishing slavery, that you yourself, Stevens, piloted through Congress. It follows from Lincoln’s policy that they therefore were entitled to the same rights as the rest of us. Now gentlemen, it’s just as simple as that.” What Johnson is referring to is that, even after they ratified the 13th Amendment, the Republicans kicked the Southern congressmen and senators out of Congress when they rejected the 14th Amendment. Stevens then offers to buy the President for another eight years, which would include a second term. When Johnson refuses, Stevens asks the other Republicans to leave so that he can have a word alone with Johnson. When Johnson asks Stevens why he wanted to see him alone, Stevens replies, “To tell you that since you’ve turned me down, I feel that I’ll have to turn you out,” being a threat of impeachment.

In the next White House meeting between Johnson and Stevens, Johnson signs a pardon and restoration of citizenship for all who fought for the Confederacy. Stevens is infuriated at this, saying, “Now every rebel snake in the South will crawl out of its hidden den into the daylight. Johnson, what you’ve done tonight and what you plan to do means a new civil war.” He then says, “I haven’t long to live, just kept alive for the day of retribution and justice so I could die happy knowing I would leave the country at peace.” This in turn infuriates Johnson, who says, “Peace? You call revenge, confiscation and disfranchisement peace?” To this, Stevens replies, “Have you no pity for those four million injured, oppressed, hopeless colored people under bondage for two centuries?” To this, Johnson then replies, “I want the two races to live together peacefully, to respect each other. Your making slaves of the whites would put that off another century.” Stevens then says, “Johnson, if you withdraw this thing, for the sake of peace, I’ll quash the impeachment.” Johnson then says, “Well, Stevens, I decline your offer, but I want to tell you one thing. I never really understood you until this minute. I always thought you wanted a puppet president you could boss. I called you a hypocrite. You’re not. You’re a very sincere man, and that is what makes you so dangerous. You have the sincerity and will and force, you have the drive of a fanatic.” This is the most important and accurate observation about Stevens in the whole movie. It summarizes what Stevens really was.

In the next scene, Stevens gets his excuse for launching the impeachment of Johnson. The Radical Republicans had passed the Tenure of Office Act over Johnson’s veto, which stated that no member of the Presidential cabinet who had been appointed by Lincoln could be removed. Secretary of War Edwin M. Staunton, portrayed by Lloyd Corrigan in the movie, was spying for Stevens and reporting the cabinet proceedings to him. Johnson felt that the Act was unconstitutional and he fired Staunton to test its constitutionality before the Supreme Court. The introduction at the beginning of the movie states, “In 1926, the Supreme Court pronounced this law unconstitutional – as Johnson had contended it was.” Staunton then informs Stevens of this firing and Stevens initiates Johnson’s impeachment over it.

Johnson never appeared at his trial and was represented by his counsel. In the movie, this happens at first until the Republicans in the Senate do not allow any of Johnson’s witnesses to testify, so Johnson goes to the Senate to testify for himself. In his movie speech before the Senate, Johnson says that the charges brought against him are a ruse and that the real issue on trial was union. He said in part: “I thought the war had ended. It seems so. No enemy confronted us on any field. The hand of friendship was stretched out and I clasped it. Is forgiveness a crime? My enemies seem to think so. They’re not willing to forgive. For, senators, in this crowded chamber, there still stand twenty empty desks.” The camera then shows those desks and “The Vacant Chair” plays in the background once again. Johnson continues, “Why are those desks empty? Where are the senators who should be sitting at them? They have been lawfully elected, but they are not here. Why? The man most responsible for the fact that we are still at war, although the guns are silent, sits there at that table.” Johnson then walks toward the table at which Stevens is seated and says: “I wish to say that he is a sincere man. It is his honest belief that by pardoning the Confederate leaders I made inevitable another civil war. He hates the South with such consuming passion that he thinks, as he has said, that it must be kept in subjugation and slavery for the next hundred years. If I am removed from office, the next president who shares these sentiments of Mr. Stevens will set up a junta that will be no government of united states, but a self-perpetuating corrupt tyranny based upon bayonets, confiscation, and disfranchisement. Abraham Lincoln fought this war to restore the Union. Long ago, the fighting stopped. But while those desks remain empty, there is no Union.” While this speech never took place, the sentiments expressed in it are among the most important expressed in the movie.

After this speech, the Senate takes a vote on Johnson’s impeachment. Johnson was acquitted by one vote. The deciding vote was cast in his favor by Senator James W. Grimes of Iowa, who had to be carried into the Senate because he had suffered a stroke. He was virtually driven from political life for his courage. In the movie, he was represented as a character called Senator Huyler portrayed by William Farnum and this is one of the most suspenseful scenes in the movie. Stevens died a few months later.

After he left office as President in 1869, Johnson ran for congressman in 1872 and was defeated, but he was appointed to the US Senate in 1875. He served for four months and then he died. The final scene in the movie shows him taking his seat in the Senate before he takes the oath of office. In this speech, Johnson is at his desk and is surrounded by the senators from all the other Southern states who are all also at their desks. He states that with all of the Southern states back in the fold, the Union has at last been restored while “The Battle Cry of Freedom” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” play in the background.

One of the most important things about Tennessee Johnson for today is its accurate depiction of Thaddeus Stevens and the fanaticism that he and the Radical Republicans represented, which was commonly known at the time it came out. As one example, Claude G. Bowers was a Northern journalist, politician, and historian and was a supporter of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt, so he was certainly no conservative. He wrote a great many works of history and one of them was The Tragic Era: The Revolution after Lincoln (Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1929, 1957), which was a history of Reconstruction. In it, he described Stevens as follows:

“To him the war was an opportunity to free the slaves, to punish the South, to crush its aristocracy.”

“’The laws of war, not the Constitution,’ he growled; and we are to hear this growl from him to the end. ‘Who pleads the Constitution?’ he demanded with a scowl. ‘It is the advocates of rebels.’”

“This man in his den was as much a revolutionist as Marat in his tub. Had he lived in France in the days of the Terror, he would have pushed one of the triumvirate desperately for his place, have risen rapidly to the top through his genius and audacity and will, and probably have died by the guillotine with a sardonic smile upon his face. Living in America when he did, he was to become the most powerful dictatorial party and congressional leaders with one possible exception in American history, and to impose his revolutionary theories upon the country by sheer determination.”

“Thus there was a hardness about him that made men dread him. Time and again he was to enter a party caucus with sentiment against him to tongue-lash his followers into line. It was easier to follow that to cross him. He had all the domineering arrogance of the traditional boss. He brooked no opposition. [Carl] Schurz [a Union general] noted even in his conversation, ‘carried on with a hollow voice devoid of music…a certain absolutism of opinion with contemptuous scorn for adverse argument.’ He was a dictator who handed down his decrees, and woe to the rebel who would reject them.”

“He held no council, heeded no advice, hearkened to no warning, and with an iron will he pushed forward as his instinct bade, defying, if need be, the opinion of his time, and turning it by sheer force to his purpose.”

“The best and most pointed illustration of his humor is found in his apology to Lincoln for an unkind observation on a trait in [Simon P.] Cameron [Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury]. ‘You don’t mean to say you think Cameron would steal?’ asked Lincoln. [Stevens replied,] ‘No, I don’t think he would steal a red-hot stove.’ Finding that reply too good to keep, Lincoln repeated it to Cameron, who indignantly demanded a retraction. Stevens went forthwith to the White House. ‘Mr. Lincoln, why did you tell Cameron what I said to you?” he asked. ‘I thought is was a good joke and didn’t think it would make him mad.’ ‘Well, he is very mad and made me promise to retract. I do so now. I believe I told you he would not steal a red-hot stove. I now take that back.’ Thus, in his wit and humor there was always something of a sting.”

In The Growth of the American Republic (4th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1950), Samuel Elliot Morrison and Henry Steele Commager, both eminent historians, stated:

“Stevens is one of the most unpleasant characters in American history. A harsh, somber, friendless old man…with no redeeming spark of magnanimity, he was moved less by sympathy for the Negro than by cold hatred of the Southern gentry….[H]e would humiliate, disfranchise, and despoil…all…landed [property owners] in favor of the freedman. [Stevens sought retribution saying,] ‘I have never desired bloody punishments to any great extent…but there are punishments quite as appalling and longer remembered than death. They are more advisable because they would reach a greater number. Strip a proud nobility of their bloated estates;…send them forth to labor and teach their children to enter the workshops or handle a plow…and settle [their states] with new men and drive the present rebels as exiles from this country.’”

Thaddeus Stevens was born and raised in rural Vermont and went to the University of Vermont his first year of college, and then to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. After graduation from there, he went to York, Pennsylvania, where he became a teacher. After studying for the bar there, he became a lawyer in Gettysburg and was elected as a state representative. He later moved to Lancaster because there was more political opportunity there and was elected congressman from there. The two causes crusaded for the most were universal public education and abolitionism. Stevens himself once stated that he hoped the slaves would be “incited to insurrection and give the rebels a taste of real civil war.”

Current Marxist mythology is lauding Stevens as a hero and Johnson as a villain. Their argument centers in part on the Black Codes established under Johnson during Reconstruction, which they contend set up slavery under another name and segregation. John Chodes, in his book Segragation: Federal Policy or Racism? (Columbia, SC: Shotwell Publishing, 2017) debunks this myth, pointing out that they maintained an integrated South. He states:

“The Reconstruction-era Black Codes have been viewed as racist laws designed to re-enslave blacks. This is inaccurate. They were created under Andrew Johnson’s presidency and reflect an attempt by both the Northern conquerors and the Southern employers to develop a stable work environment that would be fair to all sides. This was imperative in the face of the chaos, devastation, and poverty in the wake of total war.

“They helped maintain the integrated society that existed before the war but now on a market-economy basis. The Black Codes defined the freedmen’s new rights and responsibilities. They gave the Negroes the right to own property, to sue and to be witness in court, where they could testify against whites. Labor contracts and apprentice laws were other aspects of the Black Codes.”

Chodes stated regarding labor contracts, “These were formulated by the Union Army. Wages were fixed by Northern judges. The carpetbag state governments enforced labor contracts, not Southern employers.”

His statement that the South was an integrated society before the war is bound to raise the eyebrows of Northerners and Marxists, but it is true. C. Van Woodward, a Yale University history professor, wrote a history of segregation entitled The Strange Career of Jim Crow (Third Revised Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974). In it, he pointed out that segregation originally started in the early 19th Century in the Northern cities, the first one to originate it being Boston, Massachusetts. In Boston, two of the neighborhoods to which blacks were segregated were called “N—-r Hill” and “New Guinea.” Van Woodward stated, “Whites of South Boston boasted in 1847 that ‘not a single colored family’ lived among them.” He also said that the other Northern cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and others, had the same thing. He said that racial discrimination against blacks was the rule in the Northern states, where they were not allowed to vote and they were excluded from being admitted as jurors. On the other hand, he points out that the most integrated part of the country at that time was the Southern cities, where the races mixed freely. Segregation was imported from the North into the South much later.

It should be noted that black disfranchisement in the Northern states existed at the same time that the Radical Republicans were demanding universal black male enfranchisement in the Southern states. And most Northern states had laws forbidding blacks to move there. The Radical Republicans had no other interest in black Southerners than as a voting block which they could manipulate in order to maintain power. Furthermore, they were not for extending such rights to Native Americans unless they paid taxes.

Today’s Marxists falsely claim that Thaddeus Stevens was the savior of black people by kicking the Southern senators and representatives out of Congress because, by his doing so, blacks were supposedly saved from re-enslavement. Of course, Marxism thrives on fomenting conflict between the alleged oppressors and the alleged oppressed. And while Confederate monuments are being systematically torn down by the Marxists and their dupes, two statues of Stevens have been erected. There were no statues of him anywhere until 2008, when one was erected in front of the Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. A second one was erected in 2022 in front of the Adams County Court House in Gettysburg. The latter was commissioned by the recently formed Thaddeus Stevens Society, which is dedicated to eulogizing him and which also opened a Thaddeus Stevens Museum in Gettysburg in 2024. The museum is across the street from a state historical marker at the site where his house once stood.

When it was released in 1942, Tennessee Johnson was protested by the NAACP and the Communist Party, USA. This film is very relevant for our day because the same vindictiveness against the South which the Radical Republicans breathed is being breathed by the Marxists today. Just one example among many which could be cited was exhibited during the dispute over the renaming of Confederate Memorial Hall at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Jonathan David Farley, a black math professor there and a native of Jamaica, said “the race problems that wrack America to this day are largely due to the fact that the Confederacy was not thoroughly destroyed, its leaders and soldiers executed and their lands given to the landless free slaves.” (Farley, “Remnants of the Confederacy: Glorifying a Time of Tyranny,” Nashville Tennesseean, November 20, 2002) A government which would have done this is the exact kind described in Johnson’s speech before the Senate in the movie as “a junta that will be no government of united states, but a self-perpetuating corrupt tyranny based upon bayonets, confiscation, and disfranchisement,” and based on murder as well. Left wing jubilation over the murder of Charlie Kirk just further shows their intentions. And today, the Democrats are the ones who are seeking vengeance on the South the way the Radical Republicans did during Reconstruction. The plot of this movie exposes both of the Radical Republicans and the Marxists for what they were and are and this movie is just as timely today as it was when it was made.

For further information on Reconstruction, two good recent books on the subject are Reconstruction: Destroying the Republic and Creating and Empire by James Ronald Kennedy (Columbia, SC: Shotwell Publishing, 2024) and Southern Reconstruction by Philip Leigh (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2017).

The screenplay was written by Milton Gunzburg, Alvin Meyers, John Balderston, and Wells Root. Produced by J. Walter Ruben

Irving Asher (uncredited) true?

Thanks for this old movie recommendation. I’ll watch it mainly because of your description of how Reconstruction was portrayed in the movie.