Jefferson’s views on Indians were characterized by ambivalence. Jefferson both loved and hated Native Americans at times because he de profundis animi (from the depths of his soul) loved Native Americans. That is not posited as a thesis, for it should be obvious to anyone who examines Jefferson’s presidential writings on Native Americans, but as an observation. Jefferson was, through his father Peter, frequently exposed early on and directly to mysterious but congenial American Indigenes, and he came to respect profoundly their courage, physical endurance, artistry, integrity, and most importantly, their large love of liberty, even if they were “uncivilized.” That observation of Natives’ love of liberty, I maintain, profoundly influenced Jefferson.

Though uncivilized, they showed marked signs to Jefferson of being readily civilizable. The embrace of liberty was, for Jefferson, key. Thus, Jefferson, qua politician and philosopher, hoped that they would mix their blood with Whites—that is, miscegenate—and become part of what he saw, he tells James Madison (27 Apr. 1809), that was a great American “empire for liberty,” covering perhaps the whole of the North American continent. That was Jefferson’s great political experiment.

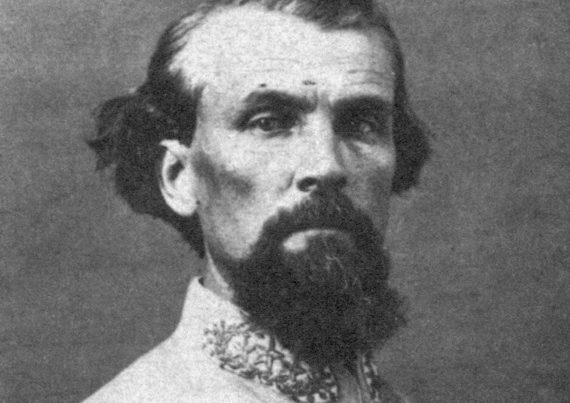

One of Jefferson’s first impressions of indigenes was warm. He writes to John Adams (11 June 1812) of a childhood memory of the great Cherokee chief Outassete (below), known for his powerful speeches. Outassete was always welcome at Shadwell when he traveled “to & from Williamsburg.” On this occasion, Outassete was speaking to his people, prior to a visit to England. The moon was full and the great chief lifted his head to it as if speaking to it. “His sounding voice, distinct articulation, animated actions, and the solemn silence of his people at their several fires, filled me with awe and veneration, altho’ I did not understand a word he uttered.”

Early impressions, it is commonly known, are lasting, and it is clear that this memory of Outassete, spellbinding his tribe, did much to shape Jefferson’s mature view of Native Americans. He writes to John Adams (11 June 1812), “In the early part of my life, I was very familiar, and acquired impressions of attachment and commiseration for them which have never been obliterated.”

Yet Jefferson’s mature view of Native Americans was typically ambivalent, for political considerations entered the picture. They, like Blacks, were albatrosses to his “empire for liberty”—the hope to spread his republicanism from the eastern Atlantic coast to western Pacific coast. Many, if not most, Indians violently resisted miscegenation. White men had uninvitedly entered the Americas and were quickly displacing them through sanguinary skirmishes and shady pacts. Despite Indians’ resistance to the encroachment of Whites, Jefferson settled on the view of admixing them into the swelling American nation, when others argued for their extermination.

Why was Jefferson committed to miscegenation?

There was, aside from Natives’ relative unwillingness to intermix, little to lose in what he called his “experiment” or “great experiment”: a test of the hypothesis that Jefferson-styled republicanism would be a marked improvement over coercive aristocracies, with, following Aristotle, coercive monarchy being the worst. Jefferson writes to Marquis de Chastellux (7 June 1785), “I am safe in affirming, that the proofs of genius given by the Indians of North America place them on a level with whites in the same uncultivated state.” The evidence comes from (1) his own interactions with them—“I have seen some thousands myself, and conversed much with them”—and from (2) the testimonies of others—“I have had much information from men who had lived among them, and whose veracity and good sense were so far known to me.” Native men are weaker than Whites, but “their manners rendering it disgraceful to labor,” which is left to Native women. Yet they are expert in the chase, tracing an enemy or beast, and in ambuscades, they are much superior to Whites. Jefferson sums, “I believe the Indian, then, to be, in body and mind, equal to the white man.”

The depiction Jefferson offers Chastellux is a précis of his extensive account of American Indigenes in Book VI of Notes on the State of Virginia, to which I now turn.

A Native American man, Jefferson asserts, has the sexual ardor and potency of Whites; perseveres in battles by “making the point of honor consist in the destruction of an enemy”; prefers stratagem to recklessness through regard for self-preservation; chooses death to surrender to an enemy; “endures tortures with a firmness unknown almost to religious enthusiasm with us”; is affectionate to and indulgent with his children; exercises fidelity in friendship; enjoys activity of body and of mind; and forms bonds of affection “from circle to circle, as they recede from the centre,” in the manner of Whites.

Yet because of the reluctance of Indian men to engage in labor, their women are “submitted to unjust drudgery,” which is “the case with every barbarous people” for whom “force is law.” Hence Native American women are drudges and physically more robust than white females.

What of the intelligence, imagination, and moral discernment of American Indians?

Concerning their genius, Jefferson writes: “To form a just estimate of their genius and mental powers, more facts are wanting, and great allowance to be made for those circumstances of their situation which call for a display of particular talents only. This done, we shall probably find that they are formed in mind as well as body, on the same module with the ‘Homo sapiens Europæus.’”

Those assertions are not very aidful. One might expect a few illustrations of Indigenes’ genius. Yet the addendum that their “situation” demands merely “a display of particular talents only,” however, is suggestive. He likely means that Natives are seldom in circumstances that call for reflection on and adoption of a general plan to approach circumstances with stark similarities. Thus, in the language of Aristotle, they used knack or experience (empeiria), not knowledge (epistēmē).

Jefferson proffers another caveat. “Before we condemn the Indians of this continent as wanting genius, we must consider that letters have not yet been introduced among them.” Thus, there are comparable to Europeans, North of the Alps, who had thitherto never been exposed to Roman arts and Roman arms. Still, that comparison falters, for Europe, at that time, was swarming with people. “Numbers produce emulation and multiply the chances of improvement, and one improvement begets another.” North America, at the time of Jefferson’s writing of his Notes on Virginia, was not swarming with people. If the Natives are similar to uncultivated Europeans, then it will take time for populational swelling and civilization through emulation. “It was sixteen centuries before a Newton could be formed.”

Jefferson is more forthcoming on Indians’ imagination, which for Jefferson and most of his time, found expression in the fine arts: painting, sculpture, poetry, oratory, and criticism, inter alia. There are, asserts Jefferson, few instances of aborigines excellence in oratory, which forms the foundation of tribal prepolities. The reason for paucity is that their oratorical skills are “displayed chiefly in their own councils.”

Yet some are “of very superior lustre.” He offers in his Notes on Virginia the speech of Mingo chief, Logan—a written speech, which is of par with any orations of Demosthenes and Cicero.

The circumstances leading to his speech are as follows. In spring 1774, two Shawnees committed a robbery and murder on an inhabitant of the frontier of Virginia. The Whites nearby sought retribution. A certain Col. Cresap—a soldier, Jefferson says, that was infamous for his crimes among aboriginals—gathered up some men and traveled down the Kanawha River in quest of vengeance. They espied a canoe with one male and several women and children, unawares, on the opposite side of the river. “Cresap and his party concealed themselves on the bank of the river, and the moment the canoe reached the shore, singled out their objects, and at one fire, killed every person in it.” The slaughtered Indians were of the family of Logan, who was till then amicably disposed towards white men. Logan sought vengeance. The atrocities resulted in a war in the autumn of 1774 at the mouth of the Kanawha River. Shawnees, Mingoes, and Delawares faced a detachment of the Virginia militia. The Indians, defeated, sued for peace. Logan would not condescend to be among those “suppliants.” Yet Logan delivered the following speech by virtue of a messenger to Virginian governor Lord Dunmore.

I appeal to any white man to say, if ever he entered Logan’s cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if ever he came cold and naked, and he cloathed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war Logan remained idle in his cabin an advocate for peace. Such was my love for the whites, that my countrymen pointed as they passed, and said, “Logan is the friend of white men.” I had even thought to have lived with you, but for the injuries of one man. Colonel Cresap, the last spring, in cold blood, and unprovoked, murdered all the relations of Logan, not sparing even my women and children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This called on me for revenge. I have sought it: I have killed many: I have fully glutted my vengeance: for my country I rejoice at the beams of peace. But do not harbour a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will not turn on his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan?—Not one.

Jefferson says little about the morality of Indians, other than, because they live in prepolities, moral discernment takes the place of laws and that they exhibit large courage in battles. There is nothing to suggest that he thinks American aboriginals are not the equals of all other men apropos of morality.

Jefferson, however, does write of their religiosity. Though spiritual people, they have nothing like priests. “In the solemn ceremonies of the Indians, the persons who direct or officiate, are their chiefs, elders and warriors, in civil ceremonies or in those of war; it is the head of the cabin in their private or particular feasts or ceremonies; and sometimes the matrons, as in their corn feasts.” In solemn ceremonies where they evoke the Great Spirit, the worthies of the nation, men and matrons, preside. “Conjurers are resorted to only for the invocation of evil spirits.”

What stands out in Jefferson’s thoughts on American Indians is their love of liberty, as indicated by their courage in war and their general refusal to integrate with Whites—something Jefferson found admirable, but ultimately infuriating. He says in his Second Inaugural Address that they are “endowed with the faculties and the rights of men” and that they breath “an ardent love of liberty and independence.” Yet confined to territories too narrow for hunting “in a country which left them no desire but to be undisturbed,” they find themselves before “the stream of overflowing population.” It is upon Americans to “teach them agriculture and the domestic arts” so they can enjoy those bodily comforts that encourage “the improvement of mind and morals.” Key albatrosses are their hidebound “anti-philosophers,” who, ever looking backward, “find an interest in keeping things in their present state, who dread reformation, and exert all their faculties to maintain the ascendency of habit over the duty of improving our reason, and obeying its mandates.” As Jefferson says in his Rockfish Gap Report, they have “a bigoted veneration for the supposed superlative wisdom of their fathers, and the preposterous idea that they are to look backward for better things.”

Enjoy the video below….

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

This is an excerpt from my soon-to-be-published book, Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence: A Document, Timely & Timeless.

Contents

Prologue

I: Jefferson’s Years as Barrister

II: Jefferson’s Summary View

III: Declaration of Independence

IV: Jefferson Comes under Attack

V: In Defense of Thomas Jefferson

VI: Are All Men Really Created Equal?

VII: Jefferson on Natives & Blacks

VIII: Jefferson on Women

Epilogue

Appendix I: The Declaration of Independence

Appendix II: Jefferson’s (First) Draft of the Declaration

Appendix III: Signatories of the Declaration of Independence

Will be buying it.

Thank you. I can have an autographed copy for you.

Do you address the argument that Thomas Paine was the substantial author of the Declaration?

He was not. He did have a profound influence on the Colonists….

What is a “substantial author”?

I mean somewhat who contributed a substantial amount of the work done by a group. Like the Constitution, many of the most famous and important documents from that era had multiple drafts and multiple authors or editors (the Committee of Five, in this case). Here is a good summary of one of the theories floating around out there, one that states that Pain authored the first draft and Jefferson merely altered it a bit:

https://themillenniumreport.com/2017/07/its-true-thomas-paine-really-did-write-the-declaration-of-independence/

The evidence is largely circumstantial and textual in nature, but as a millennial who watched the big names in mainstream history “die, muscle by muscle,” as John Randolph said of Webster when he faced Calhoun, lose all credibility on so many topics when faced by non-court historians, I found the theory at least interesting and wondered if you had written something in refutation or approval.

Typo: it should read “someone,” not “somewhat.”

There are no “native Americans”. All humans residing in the New World prior to Columbus’ voyage were on average a 50/50 mix of Asian and Caucasian dna.

I offered this to some of the geniuses on FB the other day in response to their brilliant observations about “indigenous'” people terrorism etc.

I was roundly laughed at. I t is difficult to imagine the survival of society with the collection of newborn fools spreading throughout the world.

Keep teaching the willing…those who are philosophically opposed to you will also benefit from your wisdom. I love a good challenge…there are so many who know absolutely nothing about almost everything. The world is our oyster. There has never been such a time where truth can be broadcast to the masses. I am amazed the controllers ever sold us their monopoly on the message for a few eyeball “likes”.

I can supply an autographed copy to some 6 or so mavens. Should be out in 3 months.

I fully address that in my book. I write in my preface:

Throughout the book, I use “American Indians,” “American Aborigines,”

“Native Americans,” “Indians,” “Aborigenes,” and “Natives”—the last three were

typically used in Jefferson’s day and should not be taken as pejorative or as

depriving American Indians of personhood—as equivalent terms to refer to

Native Americans in the aggregate. That does not imply that each of the various

tribes or nations of Indians—and the number of tribes throughout North

America was very large—had numerous cultural commonalities with all others.

It is merely a convenience that enables me—as it did, for instance, Jefferson,

Washington before him, and Jackson after him—to write about the Aboriginal

people he encountered in the aggregate, which was typically done in Jefferson’s

day. As we shall see, that is in large part the reason why the Early American

Indian policy failed. Political policies tended to deal with Indians in the

aggregate, while the ethnoi of the numerous tribes were many and varied.

I discuss that and TJ’s view that Asians were originally from N. America in my book Thomas Jefferson and American Indians.

Looking backwards, for better things. Indeed