They sailed into Brazil more through memory than fact now, not as tourists or traders but as refugees from a vanquished republic. Between 1865 and 1875, an estimated 2,000 to 4,000 former Confederates left the wreckage of the American South and started over in the Empire of Brazil. Their exodus counted among the largest political departures of United States citizens in the country’s history.

The South they left behind felt unrecognizable. Four years of civil war had burned cities, shattered railroads, and ended the plantation system that had underpinned their wealth. Others could not accept what they saw as occupation by Northern troops and a reconstruction policy they regarded as dictatorial rule.

Dr. George Scarborough Barnsley captured that mood perfectly. The Confederate surgeon whose family plantation in Georgia lay in ruins wrote to his father in 1865 that he had no hope but emigration and could not in good conscience swear loyalty to the federal government. He described himself as utterly ruined in hopes and in fortune and asked why he should remain to weep over war torn graves.

While the South smoldered, Brazil made a calculated offer. Emperor Dom Pedro II had quietly favored the Confederacy during the war, permitting Southern ships to use Brazilian ports. After Appomattox, he moved from sympathy to recruitment. The emperor wanted experienced cotton planters and saw the defeated Southerners as a ready-made class of experts.

Brazil sweetened the invitation with tangible benefits. The imperial government offered land for as little as $.22 per acre, subsidized ocean passage, temporary lodging, quick citizenship papers, and exemptions from military service.

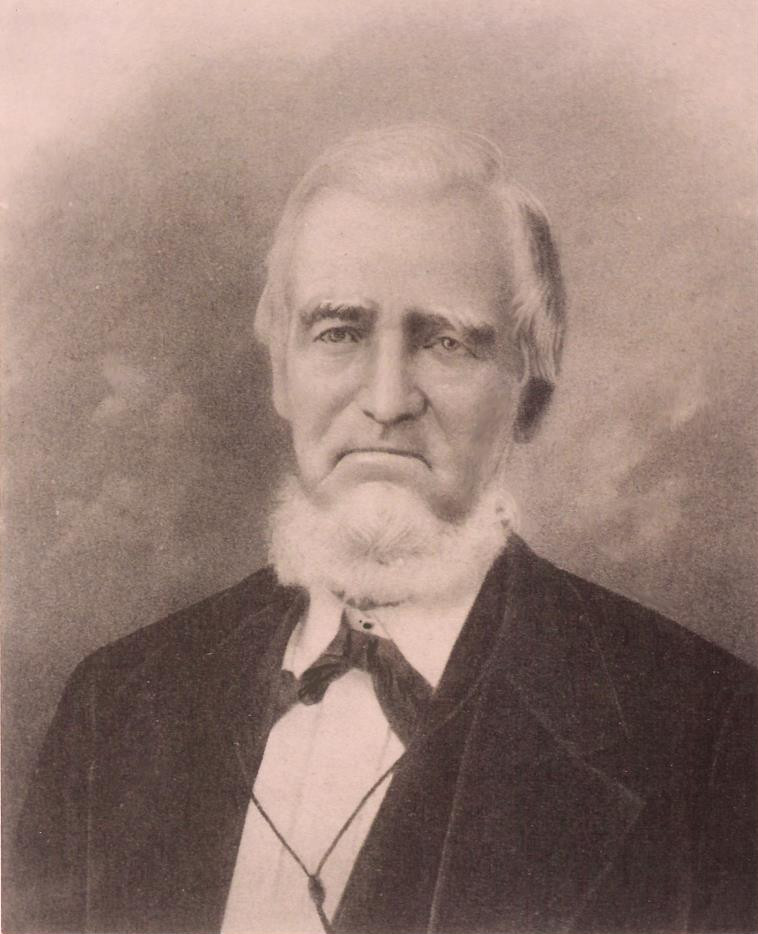

William Hutchinson Norris emerged as the movement’s most prominent leader. The Georgian had served in the Alabama legislature and risen to become Grand Master of the state Masonic lodge. On December 27, 1865, Norris, his brother Frank, and his son Robert sailed into Rio de Janeiro aboard the ship South America. Norris bought roughly four to six hundred acres of farmland in São Paulo and planted a colony.

When the railroad reached his settlement in 1870, Brazilians began calling the terminus the Village of the Americans. Today the municipality of Americana stands as a living monument to the Alabama senator who became an imperial congressman in Brazil and died there in 1893.

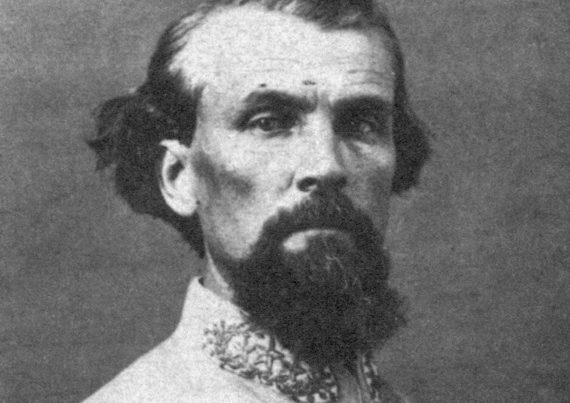

Francis McMullan led one of the most ambitious efforts. The Georgian had served under William Walker in the failed bid to seize Nicaragua before joining the Confederacy. He partnered with Colonel William Bowen to organize a colony of 154 Texans who secured 50 square leagues on the São Lourenço River and christened it New Texas.

Their passage brimmed with drama. The colonists boarded the brig Derby in January 1867, but the voyage erupted in mutiny when passengers discovered the captain had colluded in delays and illegal fines. A tropical storm drove the Derby onto the Cuban coast and broke the ship. McMullan gathered his people, reached New York, and secured space on the steamer North America.

McMullan fell gravely ill with tuberculosis and died at Iguape on September 29, 1867, less than eight months after leaving Texas. His colony nevertheless introduced the moldboard plow and modern agriculture to Brazil, established a Baptist church, and helped shape the Brazilian school system.

Dr. James McFadden Gaston, a respected South Carolina surgeon, joined a group of colony scouts in August 1865. The Brazilian government made him liaison among all the scouting parties. His 1866 volume, Hunting a Home in Brazil, urged his countrymen to flee what he called the disturbed state of society in the United States. Gaston settled in Campinas, built a medical practice, returned to the United States in 1883, and gained a professorship in surgery.

Charles Grandison Gunter had served in the Alabama House and championed legislation allowing married women to hold property. After the war, he moved to Brazil, bought enslaved laborers, and founded a settlement at Rio Doce.

Reverend Ballard Smith Dunn served as chaplain and ordnance officer in the Confederate army. He reached Rio in October 1865 and signed an agreement for 614,000 acres at $.43 per acre, naming the colony Lizzieland after his wife. In his book Brazil, the Home for Southerners, he likened fellow Confederates to a family of field mice cut through by a plowshare.

Benjamin Cunningham Yancey and his brother Dalton were sons of William Lowndes Yancey, known as the voice of secession. Benjamin graduated from the University of Alabama in 1856 and commanded artillery at Murfreesboro. He spent thirteen years in Brazil, where he married Lucy Cairnes Hall in 1873 before returning to Florida. Dalton became Lake County’s first judge and a Florida state senator.

Henry Farrar Steagall enlisted in 1862 and was captured at Vicksburg. In 1867 he migrated to Brazil and settled in Santa Bárbara d’Oeste, where he died in 1888. His descendant Roberto Steagall fought in the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution. Roberto’s tombstone bears the inscription “Once a rebel. Twice a rebel.”

The Confederados quietly rewrote Brazil’s agricultural script. They brought Georgia Rattlesnake watermelons, which Brazil had never cultivated before. Southerners introduced pecan trees, new rice strains, and improved cotton. They brought the moldboard plow, which cut and turned Brazilian soil far better than local tools. These changes helped move Brazil toward its later role as a major agricultural exporter.

Religion followed the plows and seeds. Church law barred Protestants from Catholic cemeteries, so the Confederados built their own Campo Cemetery in Santa Bárbara d’Oeste. They raised chapels that served as makeshift churches and schools.

On September 10, 1871, Pastors Richard Ratcliff and Robert Porter Thomas joined eight other Baptist Freemasons and formally organized what scholars regard as the first Baptist church on Brazilian soil.

Reverend Junius Eastham Newman arrived in August 1867 and organized the first Methodist congregation at Saltinho in 1871. The Methodist Episcopal Church South sent its first official missionary to Rio in 1876, 35 years after earlier attempts at a Methodist presence.

Reverend William Emerson and Reverend William Macfadden established Presbyterian congregations. The overlap of Freemasonry and Protestant mission work helped plant Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian roots in Catholic soil.

The Confederados established schools across São Paulo. The state adopted elements of Confederate school models into its public education system. German immigrants later built a large textile factory in Americana on this Southern agricultural base.

Descendants organized the Fraternity of American Descendants in 1954. For decades, families gathered each April at the Campo Cemetery for the Festa Confederada, where they waved Confederate flags, wore Civil War uniforms, danced square dances, and served dishes merging Southern cooking with Brazilian ingredients. American style houses stand beside traditional Brazilian structures across the region.

In June 2022, the Santa Bárbara d’Oeste city council voted unanimously to ban public display of the Confederate flag at festivals. Historian Sidney Aguilar Filho told reporters that “using the Confederate flag in our time indicates a racist interpretation of the world.” Organizers renamed the festival Festa dos Americanos and retired Confederate symbols.

Yet the Confederados still stand in Brazilian history as agents of transformation. They modernized farming, planted Protestant Christianity in Catholic land, opened schools, and laid agricultural foundations for later industry. What began as defeat and exile turned into stubborn perseverance and complicated integration. Men who fought under a rebel banner crossed an ocean, swore new oaths, and helped reshape a distant empire.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

Now they are banned from celebrating their heritage in public spaces!! In Brazil! To Hell with our enemies. Sometimes I’m in the John Taylor mood. Other times, I’m 100% Martin Gary. You can celebrate drag queen story time with young kids. You can rape women in Europe and not even be deported-sometimes not even get jail time. But they will arrest you for Facebook posts! As long you die for Israel that’s all the matters. And disown your land, kith, kin, and Faith. To Hell with them. Best to be a Confederate. You want scholar stuff? Okay, here goes. Let me quote the great Arthur Lee:

“I would rather be free, though in a ditch, than a slave in fine houses.” Welcome to Rhodesia America. Live free or die. Give me liberty or give me death. 1776 or 1865? 1876 or 1965?

I wrote a great reply Pingback, but it wasn’t accepted. It was classic General Kromwell. I must have offended the filters.

Uh-oh, seems like me personifying more my Martin Gary self has activated the safety filters and my comments now have to be moderated. I thought me quoting the great Arthur Lee would show my scholarly worth, lol. I’ll just keep it simple in the future: What would George Washington do?

To Pingback, thanks for the link and links. I’m checking them out now. My response to you was beautiful. But the message got erased after I clicked submit. Too bad. Here’s a short, non poetic version, lol:

So I can’t fly a confederate flag too high if it violates some ordinance, but I’m forced to look upon a Hindu statue taller than the Statue of Liberty?!??! Diversity is our strength.

The Masonic aspect really interested me. /G\

My family, the Page family of Virginia were Confederates, man woman and child.

Our ancestor cousin, Thomas Jefferson Page (Rosewell branch) had mapped the Amazon before hostilities then became a Confederate Admiral and when word of Appomattox reached him, “he turned his ship around, and sailed to Brazil”

Our Brazilian kin most dedicated today, to our family society in Virginia.

Thank you !!