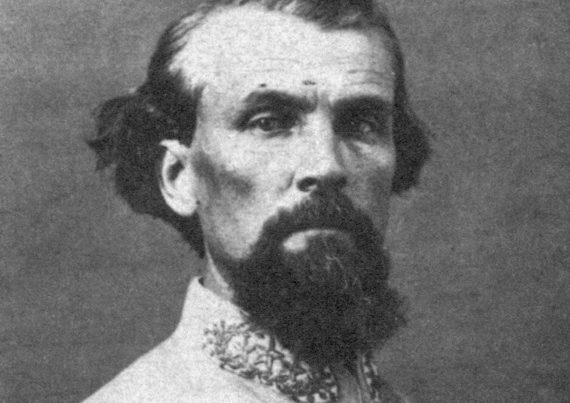

Narciso López de Urriola entered the world on November 2, 1797, in Caracas, Venezuela, born to a family of prosperous Basque merchants who enjoyed considerable colonial privilege. His relatives navigated the turbulent Venezuelan Wars of Independence by pledging allegiance to the Spanish crown. History would deliver a bitter irony when this young man, who would eventually epitomize Caribbean liberation movements, first wielded weapons against the continent’s greatest freedom fighter, Simón Bolívar.

During his youth, López enlisted in the Spanish army and participated in military operations against Bolívar’s revolutionary forces, ascending swiftly through the imperial military hierarchy while engaging in Venezuela’s most critical battles during the War of Independence. He attained colonel’s rank at the age of 31. Following Spain’s ultimate military collapse, López evacuated with the retreating Spanish forces to Cuba. Having fought at the pivotal Battle of Lake Maracaibo in 1823, López departed with the defeated Spanish troops to the Caribbean island, where he would establish himself for the following twenty years.

He married María Dolores in 1825, whose brother held the title Count of Pozos Dulces, thereby securing his position within Cuba’s aristocratic circles. López served the Spanish crown during the First Carlist War and occupied distinguished governmental roles, including the position of military governor in Madrid.

Yet circumstances changed dramatically. López lost his governmental appointment when Cuba received a new governor in 1843. A series of unsuccessful commercial enterprises ensued. The Spanish military officer who had battled against republican movements experienced a remarkable ideological reversal, aligning himself with Cuba’s anti-colonial movement. When Spanish officials launched their suppression of revolutionary activity in 1848, López escaped to the United States facing capital punishment, bringing only his martial expertise and insurgent fervor.

López initially operated from New York City, cultivating relationships with Cuban expatriates and American entrepreneurs eager for Caribbean territorial gains. However, he soon understood that his military venture required backing from the American South. He transferred his operations to New Orleans, an ideal staging ground for revolution. The Louisiana harbor city offered proximity to Cuba, sheltered numerous Latin American political refugees, and attracted wealthy residents who envisioned a Caribbean slaveholding domain anchored by their prosperous commercial center.

Southern agricultural magnates and elected officials viewed Cuba as representing something far beyond simple territorial expansion. The island offered the prospect of a new slave state capable of shifting congressional power back toward Southern interests. Projections suggested Cuba could send 13 or 15 representatives to Congress, fundamentally reshaping the political equilibrium during a period when regional conflicts threatened national unity.

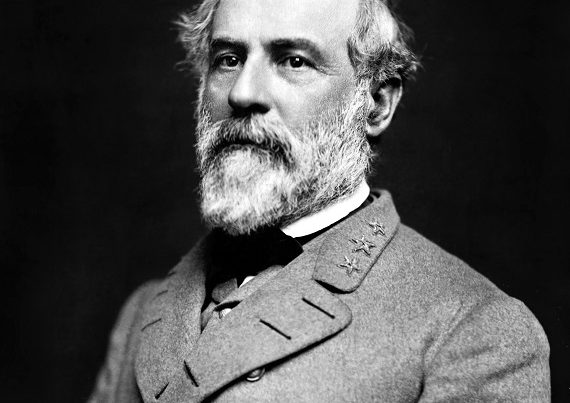

López pursued the South’s most powerful military and political personalities in his enlistment campaign. He approached Senator Jefferson Davis proposing $100,000 plus “a very fine coffee plantation” in return for military leadership. Davis declined citing his senatorial obligations, though he suggested another prominent Southern military figure. López subsequently contacted Robert E. Lee, who had received Davis’s recommendation. Lee similarly spurned the proposition, with both gentlemen concluding such participation would compromise their official positions.

López secured the monetary and political backing of numerous powerful Southerners, notably Governor John A. Quitman of Mississippi. A slaveholder and Mexican War veteran who had commanded the Mexico City assault and administered the conquered capital, Quitman personified Southern territorial ambitions. Though he first refused to command the initial invasion, he subsequently became heavily committed to López’s mission and organized his own Cuban military venture. Conversely, Senator John C. Calhoun, among the Senate’s most vigorous advocates for states’ sovereignty, voiced sympathy for López’s plans but provided no tangible assistance.

López’s movement inspired the establishment of an influential clandestine organization named the Order of the Lone Star, which expanded throughout the South with 50 chapters across 8 Southern states and membership estimates ranging from 15,000 to 20,000. The Order emerged in September 1851 dedicated to liberating Cuba from Spanish dominion and incorporating it into the United States. It constituted one of Antebellum America’s most substantial organized territorial expansionist campaigns.

Among López’s most lasting contributions originated not in Cuba but within the United States. During 1849 in New York City, López conceived what would evolve into the contemporary Cuban flag. Cuban poet Miguel Teurbe Tolón collaborated with López on the flag’s design. Emilia Teurbe Tolón, Miguel’s spouse, stitched the original banner, gaining acknowledgment as the Cuban equivalent of Betsy Ross. The design borrowed from the American flag’s aesthetic. The solitary star signified the anticipated new state joining the U.S. flag for the prospective State of Cuba, while the red triangle symbolized fortitude and steadfastness, potentially incorporating Masonic symbolism. López and numerous associates belonged to Freemasonry. This standard first flew during combat at Cárdenas in 1850 and officially became Cuba’s national emblem in 1902.

López organized three major military campaigns against Cuba spanning 1849 to 1851, each concluding unsuccessfully yet amplifying his legendary status with every venture. During 1849, approximately 600 volunteers assembled on Round Island, Mississippi, preparing three vessels for departure. President Zachary Taylor, firmly opposing filibustering activities, ordered the fleet confiscated. The expedition disbanded by September 9.

The May 1850 campaign achieved greater initial success. López obtained $50,000 through bond sales and enlisted 500 fighters, whose forces seized the coastal municipality of Cárdenas, positioned fewer than 100 miles from Havana. The Cuban flag flew over Cuban territory for the first time. Yet the anticipated popular insurrection never occurred. Spanish military units initiated a counteroffensive, compelling López to withdraw. Following his American return, authorities arrested him though prosecutors quickly abandoned the case.

López’s August 1851 expedition proved his most audacious and catastrophic undertaking. The campaign departed New Orleans aboard the steamship Pampero on August 3, 1851. The contingent numbered over 400 men comprising Southerners, Irish and German immigrants, Hungarian refugees, Cuban exiles, and various New Yorkers. Colonel William Logan Crittenden, nephew to U.S. Attorney General John J. Crittenden, led a regiment. They landed at Morillos village on August 12.

Catastrophe unfolded rapidly. López advanced inland, leaving Crittenden commanding a detachment of 100 soldiers. Spanish troops swiftly encircled Crittenden’s company, who frantically attempted escape aboard four small fishing craft. The Spanish vessel Habanero captured them on the 15th. Crittenden alongside 50 troops faced execution in Havana as pirates on August 16, 1851.

Spanish forces captured López himself on August 28 following betrayal by Cuban peasants who delivered him to Spanish General Enna. Not one Cuban civilian had rallied to his campaign. On September 1, 1851, authorities executed Narciso López via garrote in a plaza at the Punta fortress overlooking Havana’s harbor. The garrote consisted of an iron seat fitted with a metal collar that asphyxiated the condemned through screw rotation.

Before thousands of spectators, López ascended the scaffold. His final declaration resonated through the plaza: “I most solemnly, in this last awful moment of my life, ask your pardon for any injury I have caused you. It was not my wish to injure anyone, my object was your freedom and happiness.” The executioner, a Black man, positioned the iron restraints around his neck, and with the screw’s turn, López’s three-year crusade to conquer Cuba concluded.

Reports of the executions sparked violent disturbances in New Orleans, Mobile, and Key West causing thousands of dollars in destruction to Spanish assets. In New Orleans, angry crowds stormed Spanish-language newspaper offices and assaulted the Spanish consulate. Americans nationwide, throughout both North and South, expressed outrage.

After López’s death, his New Orleans collaborators formalized the Order of the Lone Star, guaranteeing his memory would perpetuate Southern expansionist ideology. Though López perished defeated, his influence persisted. His designed flag became Cuba’s national symbol in 1902. His military expeditions inspired subsequent filibusters, particularly William Walker’s Nicaraguan invasions. The profound Southern endorsement of his objective, from gubernatorial offices to secret organizations, exposed how thoroughly slavery’s preservation motivated Antebellum foreign policy.

Narciso López embodies contradiction. A Venezuelan who opposed Bolívar. A Spanish officer transformed into a revolutionary. A filibuster whose supreme achievement was not Cuban liberation, but rather a flag that survived both the Spanish Empire and his Southern allies.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.