In 1885, there was published in Lynchburg by James B. Ward a small manuscript, titled The Beale Papers, Containing Authentic Statements Regarding the Treasure Buried in 1819 and 1821 near Bufords, in Bedford County, Virginia, and Which Has Never Been Recovered. The pamphlet, which sold for 50 cents, contained three ciphertexts. A ciphertext is a matter of encrypting or encoding the text of a language, here English, so that only persons authorized with the code can read it. For instance, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, using a cipher, encrypted parts of letters to each other because their letters were often opened and read at post offices. The booklet also contained Ward’s account of how he came in possession of those texts and of how he deciphered the second text.

Of the three ciphertexts—crafted, says Ward, by a certain Thomas Jefferson Beale—only one has been deciphered. It reads:

I have deposited in the county of Bedford, about four miles from Buford’s [Tavern in Lynchburg], in an excavation or vault, six feet below the surface of the ground, the following articles, belonging jointly to the parties whose names are given in number three, herewith:

The first deposit consisted of ten hundred and fourteen pounds of gold, and thirty-eight hundred and twelve pounds of silver, deposited Nov. eighteen nineteen. The second was made Dec. eighteen twenty-one, and consisted of nineteen hundred and seven pounds of gold, and twelve hundred and eighty-eight of silver; also jewels, obtained in St. Louis in exchange to save transportation, and valued at thirteen thousand dollars.

The above is securely packed in iron pots, with iron covers. The vault is roughly lined with stone, and the vessels rest on solid stone, and are covered with others. Paper number one describes the exact locality of the vault, so that no difficulty will be had in finding it.

Ward writes that the innkeeper of Buford’s Tavern was then Robert Morriss. As Ward’s story goes, Morriss in 1822 received from Beale an iron box with the encryptions and two 1822 letters from Beale to Morriss. Thereafter, Beale, wrote Morriss from St. Louis on May 9, 1822, with instructions concerning the box. He pledged to send a deciphering key from a friend in June 1832. The key was never received, says Ward, and Beale was never again seen.

Morriss opened the box some 23 years after its reception, but failed to decipher the text. He then passed on its contents to a friend, J.B. Ward of Lynchburg, after he shared his secret with Ward in 1862. Ward deciphered the second text, but failed with the other two. He then made public the three ciphertexts, with a plain illustration of how he deciphered the second by working from the numbers of encryption 2 to English and using Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence as a deciphering tool—in the published manuscript. The booklet also contained the letter from St. Louis as well as the two letters to Morriss from Lynchburg that were in the box with the encryptions (4 Jan. 1822 and 5 Jan. 1822)

Were the ciphertexts part of a hoax or are the treasures real?

If the treasures are real, there are key difficulties.

First, it is impossible to confirm the existence of T.J. Beale and good reasons to believe that such a person never existed. There is a story, presumably from Morriss, of Beale, which was passed on by Ward when he published the ciphertexts.

Such a man was Thomas Jefferson Beale, as he appeared in 1820, and in his subsequent visits to my house [inn]. He registered simple from Virginia, but I am of the impression he was from some western portion of the State. Curiously enough, he never adverted to his family or to his antecedents, nor did I question him concerning them, as I would have done had I dreamed of the interest that in the future would attach to his name.

Yet Joe Nickell in “Discovered: The Secret of Beale’s Treasure,” writes of Beale’s name:

If Thomas Jefferson Beale is fictitious, there seems a ready explanation for the attachment of that name to a hoax concerning a treasure trove: Thomas Jefferson … for the author of the Declaration of Independence (on which the solved cipher was based), and Beale, appropriately, after a man of that name [Edward Fitzgerald Beale] who carried to the East both the news of, and the first gold from, the California gold strike.

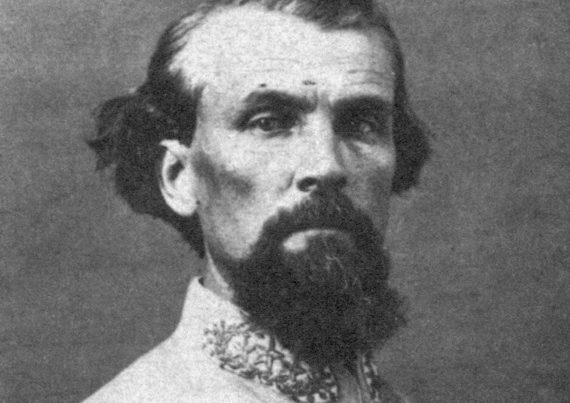

The Beale to whom Nickell refers is Edward Fitzgerald Beale (1822–93), and American frontiersman who was noted, among other things, for being the first person to bring news to the East of the California gold strike.

Another problem is Ward’s account of his first meeting with Beale. “It was in the month of January, 1820, while keeping the Washington Hotel, that I first saw and became acquainted with Beale.” Beale then stayed the winter with Morriss at that hotel. Yet records indicate that Morriss had not become proprietor of the inn prior until 1823 or 1824. According to Lynchburg Virginian (17 Apr. 1826), Morriss “has moved from the Washington, which he has occupied for more than two years past, to the Franklin Hotel.” That squares with Lynchburg’s historian Margaret Couch Cabell, who writes: “In the year 1824, Mr. Morriss took possession of the Washington House, which he kept with great success for several years; then he moved to the Franklin Hotel, of which he was the worthy and beloved proprietor for a length of time, dispensing to all around him his unbound kindness.” How could Beale have stayed with Morriss at a place at which he at the time was not?

Finally, there are the data of stylometric analysis. In 1982, linguist Dr. Jean Pival studied the documents avowedly written by Beale and those known to have been written by James Ward. Pival found distinct similarities: e.g., misuse of reflexive pronouns and frequent use of negative passive phrases such as “never to be told” and “never to be realized.” Pival concluded that the different documents were crafted by the same person—a strong argument for common authorship.

The weight of the evidence evinces that the mystery is not mysterious. The account of burying treasure, worth millions, is very likely a hoax.

Thus, though the mystery is not decisively solved, there is little reason to try to cipher the two texts not yet deciphered and little reason to pick up a shovel and pickaxe and begin to dig in Bedford County.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.