Most Americans continue to believe that Southerners invented secession (and nullification) as a defensive tactic to preserve slavery, and by “most Americans” I include so-called “conservatives” like Francis Sempa at The American Spectator and Hayden Daniel at The Federalist.

According to this narrative, secession and nullification were little more than treasonous and petulant responses to justifiable federal laws. Both Sempa and Daniel argue that the modern Democratic Party resembles the racist slave-holding aristocracy of the nineteenth century, a collection of men who unjustifiably wished to tear the Union asunder in defense of slavery and racism. They had no motive other than power and no moral or political rationale for their rhetoric or actions. In short, when Lincoln sent in the troops and Jackson threatened to hang South Carolinians, those traitors deserved it.

If these articles are representative of their accumulated knowledge, neither Sempa nor Daniel know much about Southern history, or for that matter, American history.

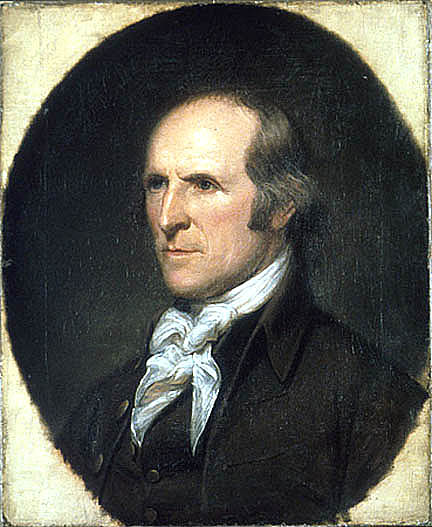

In 1804, following the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase, former Secretary of State and current United States Senator Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts began privately pressing for New England to secede from the Union. He feared that New England would never be in a position of power again and would be overrun by Jacobin farmers roaming the countryside with guillotines. His plans involved Aaron Burr, and when Burr failed to win election as Governor of New York, Pickering shelved his Northern Confederacy, at least for a time.

President John Adams gleefully fired Pickering near the end of his administration because he was a Hamilton stooge, but Pickering already had a reputation as an untrustworthy and scheming speculator and opportunist. Following the American War for Independence, Pickering settled in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania, an area that had been overrun with Indian violence in the 1770s. The native Pennsylvanians in that area resented the Nutmeggers (a person from Connecticut) who moved there. They attempted to deny them citizenship and expel them from the State. They literally referred to them as “Yankees.” When Washington Irving wrote The Legend of Sleepy Hollow in 1820, these were the kind of people he had in mind for Ichabod Crane. Pickering showed up from Salem, Massachusetts and sided with the Yankees in their legal dispute. He speculated in land, served as the lone delegate to the Pennsylvania Ratifying Convention from Luzerne County–a county he helped form with the backing of his Connecticut allies–and became fairly wealthy. He then served in the Washington and Adams administrations before returning to Massachusetts.

Pickering was always interested in New England dominance in America. He thought Southerners, and in particular Jeffersonians, were an evil democratic faction hostile to the virtuous, pious, and moral New England merchant and mechanic. He was a perfect fit for the Senate, though that body eventually censured him for reading secret documents in an open session. That led to his removal from his seat, but two years later he was back in Congress as a pro-New England and anti-war member of the House of Representatives. He never abandoned his secessionist impulses.

By 1814, Pickering was openly calling for New England to leave the Union. They flirted with treasonable blockade running during the War of 1812 and refused to send their militia into Canada. A Northern Confederation made sense, but not because Pickering wanted to be left alone. Pickering wanted New England to rule the United States.

That might sound odd, but Pickering believed New England secession would force the South to accept New England domination. He thought the South would beg for a reconstructed Union which would allow New England to dictate the terms of the reunification, including restrictions of naturalization, the removal of the three-fifths compromise to the Constitution, and a single term executive with rotation of office among the States.

He said as much in a letter to Gouverneur Morris in 1814. The recipient is important. Morris famously argued in the 1787 Philadelphia Convention that wrote the Constitution that if sectional differences were too great, the States should just agree to separate rather than be forced into an uncomfortable and unjust union. He later wrote the final draft in the Committee of Style and became one of the more important proponents of the final document during ratification. But by 1814, he was a secessionist. Like Pickering, Morris thought the South had too much power in the United States government and was waging war for territorial gain during the War of 1812, meaning he feared more agrarian slave States.

Pickering wrote to Morris in October 1814, just two months before the Hartford Convention:

To-day I had the pleasure of receiving your letter of the 17th. I was gratified to find my own sentiments corresponding with yours. “Union” is the talisman of the dominant party; and many Federalists, enchanted by the magic sound, are alarmed at every appearance of opposition to the measures of the faction, lest it should endanger the “Union.” I have never entertained such fears. On the contrary, in adverting to the ruinous system of our government for many years past, I have said: “Let the ship run aground. The shock will throw the present pilots overboard, and then competent navigators will get her once more afloat, and conduct her safely into port.” I have even gone so far as to say that a separation of the Northern section of States would be ultimately advantageous, because it would be temporary, and because in the interval the just rights of the States would be recovered and secured; that the Southern States would earnestly seek a reunion, when the rights of both would be defined and established on a more equal and therefore more durable basis.

These are two members of the founding generation who served in the highest levels of government arguing for New England secession. Neither considered it treason, and both saw it as an opportunity to curtail the power of the South. Pickering and his “Essex Junto” cohorts (including Daniel Webster) openly roasted the Madison administration and used language that Sempa called dangerous in his Spectator piece.

Pickering virtually disappeared from political life after the embarrassing failure of the Hartford Convention in 1815. He died in 1829. Morris died in 1816 after he attempted to use a whale bone to dislodge urinary stones. Webster went to Congress as an anti-war, pro-New England congressman in 1812.

Fast forward forty years. By this point, “nationalism” had become synonymous with New England sectionalism, thanks in large part to Webster in the 1830s, and Southerners now complained of being dominated by New England partisan zealots who pursued legislation that would make the South a permanent political minority.

Southern “fire-eater” Robert Barnwell Rhett of South Carolina is mostly forgotten today. Sempa identified him as one of the precursors to Tim Walz in Minnesota. He certainly favored secession. As early as the 1830s, Rhett thought South Carolina needed to bolt the Union. This was right around the time Daniel Webster engaged in his famous debates with Robert Hayne and John C. Calhoun on the meaning of Union. Black Dan forgot all about his secessionist inclinations of 1812 and launched into a “nationalist” defense of tariffs and the Constitution, the same Constitution he thought had been violated by the South just twenty years earlier.

Rhett, like Pickering, thought the Union was dead long before secession winter in 1860-61. And like Pickering, Rhett never gave up on secession. But unlike Pickering, Rhett and South Carolina pulled it off in 1860. And while their motivation seemed similar–defense of their State against perceived domination by sectional enemies–their favored outcome was dramatically different. Pickering wished to dominate the South and the Union. Rhett wanted to be left alone and argued for South Carolina secession even if other Southern States failed to join her. He thought unified action by the Southern States would be preferable, but South Carolina could pursue independence alone if necessary.

As he wrote in 1860, “All we demand of other peoples is, to be left alone, to work out our own high destinies.”Other Southern leaders would parrot this sentiment during the War.

Rhett’s defense of secession was a comprehensive indictment of Northern action against the South for the first eighty years of American history. He considered attacks on slavery to be central to the immediate sectional conflict, the grist for the mill so to speak, but unlike Christopher G. Memminger’s Declaration of Causes which centered almost entirely on slavery (Memminger had never been a staunch secessionist), Rhett explained that every issue was wrapped around the Constitutional issues of self-government and strict construction, even slavery. The North, he argued, wanted to dominate the South.

He had reason to believe this. Pickering and the early-nineteenth century New England Federalists made that clear throughout their public and private denunciations of the American political system. But Rhett never thought secession would lead to reunion. He did not believe in conventions or Constitutional amendments, and never argued that the South should coerce the North into a Southern dominated Union. That would have been political suicide. The North would continue to exist as the United States of America with its own Constitution and political economy. The South would then be unmolested by Northern attacks.

Modern readers would find Rhett’s language uncomfortable. He defended slavery was a progressive labor institution free from the pitfalls of free-wage capitalism. In other words, Rhett thought slavery’s cradle to grave protections made it preferable for workers and better for society as a whole. This was the paternalism that Eugene Genovese wrote about so often. But focusing on slavery misses the larger picture.

The South never wanted to force the North to adopt its institutions or political economy. The same cannot be said for the North. In 1794, when Oliver Ellsworth and Rufus King approached John Taylor of Caroline in a Senate cloakroom about the possibility of Northern secession, Taylor was shocked. He did not agree with the remedy to the growing sectional divide in America and argued the Union should benefit all and burden all equally. Taylor was a true Unionist.

When that Union failed in its objectives, Americans, North and South, began thinking of a way out. But Northerners always dreamed of a world where they held uncontrolled political power. Secession in 1815 and Union in 1861 offered that prospect.

Southerners were always interested in a real and equal Union of States, and when they believed that was no longer possible, they wanted to be left alone.There’s nothing more American than self-determination. The history of the United States proves it.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

As they say, great minds think alike. Great article.

The next time you read the typical drivel pseudo-historian hacks or trolls post anywhere give them a link to this article by Dr. ‘M’. It will not change the mind of the hack/troll but some people will read the link and at least begin to think about the narrative Yankee propaganda has been peddling for 160+ years. One little step at a time my fellow Sothroners. Thanks Dr. McClanahan for more Real History that none of us were taught in Yankee Publik Skool.

Excellent work, Professor McClanahan!

Great historical detail. The States had the right to secede…because they never surrendered that right when they joined in the federal union. What kind of marriage is it that doesn’t allow divorce? A tyrannical one.