A review of Luigi Marco Bassani’s Liberty, State, & Union: The Political Theory of Thomas Jefferson (Mercer, 2010).

I am always appreciative when I can read the title of some book and it gives me some idea of the content of the book and its thesis. That might seem like a claim, mundane and perhaps even foolish. Are not all titles of a book indicative of the content and thesis of that book?

That is not the case. Consider Peter Onuf’s The Mind of Thomas Jefferson and Alan Taylor’s Thomas Jefferson’s Education. The former is a skimble-skamble collection of mostly denigrative essays which Onuf threw together without a narrative thread. Its title, vague enough to accommodate lack of a thesis, tells of little of the mind of Jefferson, but much about the mind of Onuf. The latter, Thomas Jefferson’s Education, tells us nothing about Thomas Jefferson’s education. It is about Jefferson’s theory of education, and its focus is the University of Virginia. Taylor was in some sense forced into writing one book on Jefferson, as he was, after all, UVa’s Thomas Jefferson Scholar. Both books, apropos of content, are empty, valueless.

Bassani’s book is otherwise.

I came to Bassani by being asked to review his book, Chaining down Leviathan: The American Dream of Self-Government (Abbeville Press). I enjoyed the book—though there were several points of disagreement between him and me—because it was thoroughly and meticulously researched and because Bassani, unlike Onuf and Taylar, put forth a thesis and clung to it throughout the book. Last, once one read through his book, one could clearly see why he chose the title, and subtitle, he chose.

I then turned to an earlier book—Bassani’s Liberty, State, & Union—the subject of this review.

There are six chapters in the book.

The first covers Thomas Jefferson as “champion of small government.” “The aim of this work is a reconstruction of Jefferson’s political views in the twofold articulation—the rights of man and states’ rights—that represents the core of all his ideas.” Such an articulation, if it is to be correct, must place Jefferson in his proper shoes: that of a Lockean liberal, not of a Classical republican or communitarian.

Chapter 2, “Jefferson and the Republican School,” shows that the American Revolution was Lockean: fought over contravention of rights not because of communitarian ideals, such are regard for the common good, as Caroline Robbins, John Pocock, Bernard Bailyn, Lance Banning, and Gordon Wood have claimed.

There third chapter aims to show that Jefferson ever wished to be understood in his articulation of the Declaration—both his first draft and the document that has survived the heavy edits of the Congress—that “pursuit of happiness” entailed property rights. We must be mindful not to confound “the right and the object of a right”—between actions concerning ownership and mere ownership.

In chapter 4, Bassani attempts to show definitively Jefferson’s Lockean roots. Jeffersonian liberty is strictly negative: governmental non-involvement in citizens’ affairs. He illustrates with an 1802 quote from Jefferson in a letter to Dr. Thomas Cooper.

The path we have to pursue is so quiet that we have nothing scarcely to propose to our Legislature. A noiseless course, not meddling with the affairs of others, unattractive of notice, is a mark that society is going on in happiness. If we can prevent the government from wasting the labors of the people, under the pretence of taking care of them, they must become happy.

Critical to that path to happiness, pace Plato, was a right to property.

Chapter 5 is titled “American Constitutionalism.” Bassini’s aim is to situate Jefferson, then in Paris as minister to France, as participant in the discussion about the US constitution-to-be. Jefferson had no direct role, but he did advise others through critical letters. Those critical letters show that Jefferson wished the Federal government should be a union concerning the states’ affairs with foreign nations, but otherwise uninvolved in states’ matters. The states were overall to be sovereign.

The final chapter covers states’ rights and what Bassani considers to be the greatest of Jefferson’s political documents: the Kentucky Resolutions. In gist, for Bassani, Jefferson was champion of government of and for the people, but that was in need of qualification. He was not championing the rights of American people, but of Carolinians, Virginians, and Georgians, etc.

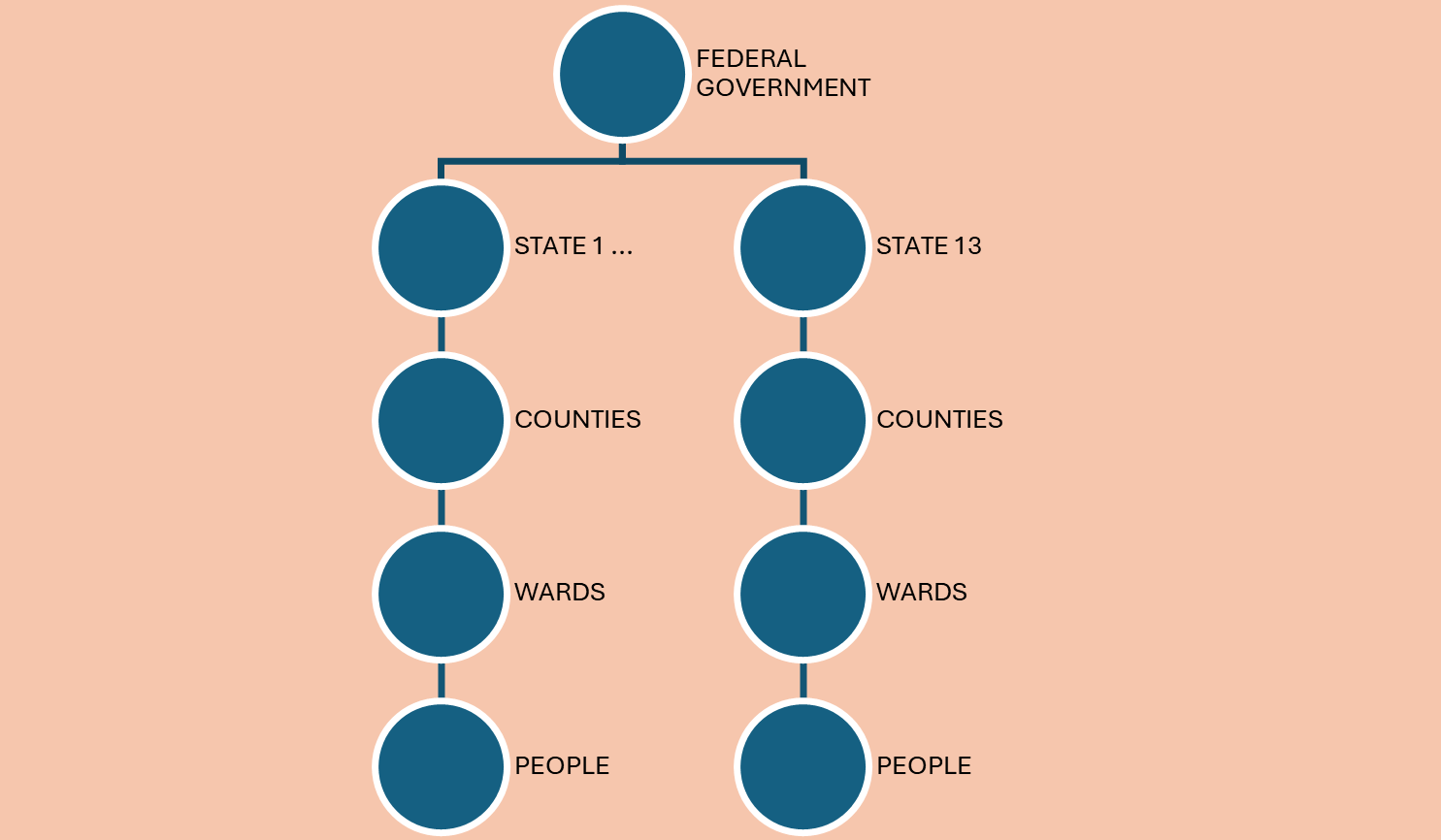

When I interviewed Bassani (below) on January 27, 2026, I maintained that one could grasp Jefferson’s uptake of Lockean negative liberty through Jefferson’s many iterations of “divide, and divide again.” We divide the federal government into its states; its states, into counties; its counties, into wards; till we get to the American people (Figure 1).

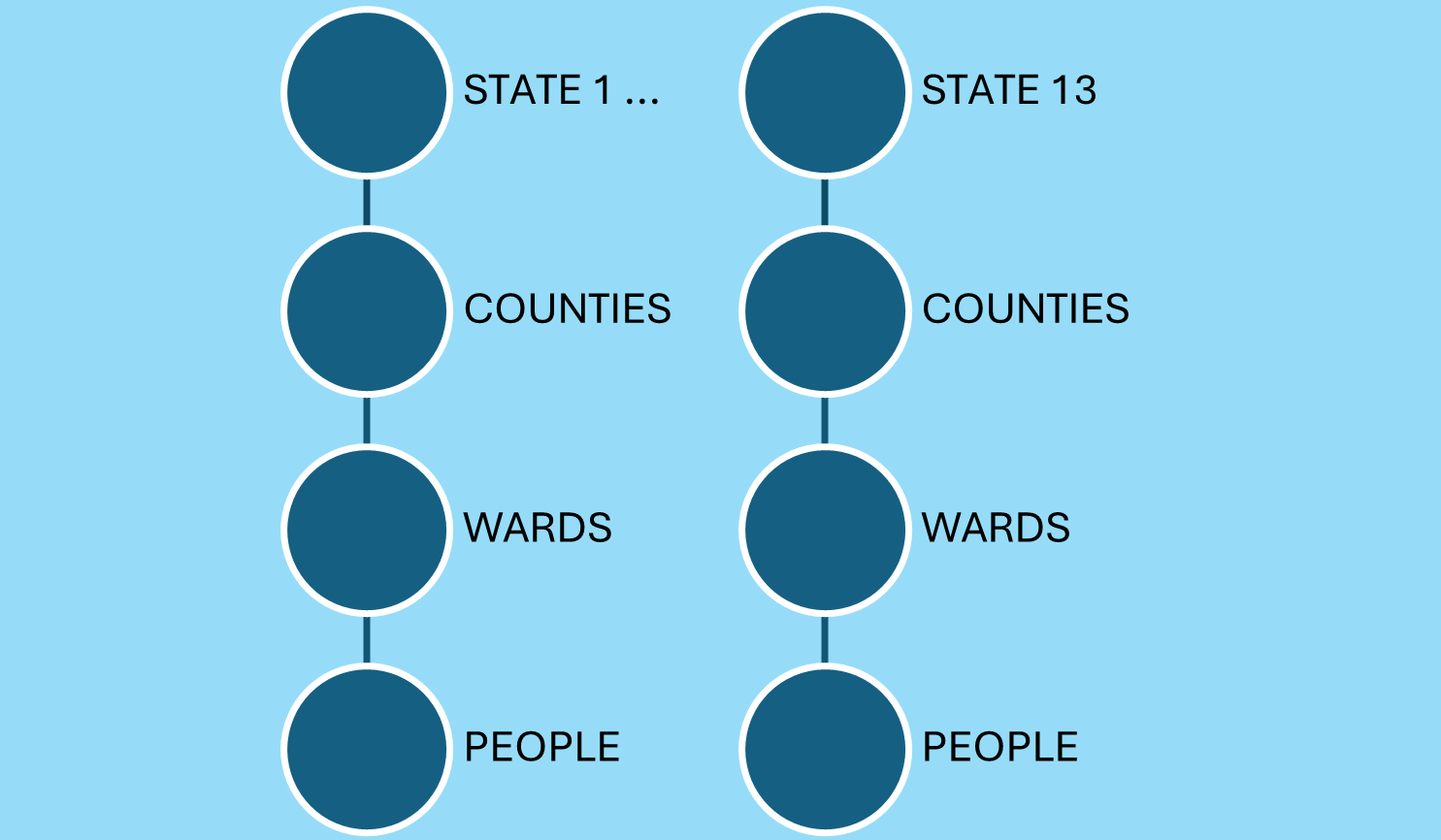

Bassani said nothing in contradiction, but he was uneasy. I think that he would have preferred me to speak thus: There is the federal government, whose sole roles are to preserve citizens’ rights and to conduct foreign affairs, with the interests of each state being considered. Otherwise, it is a nonentity. Then there are the states, where the real dividing beings (Figure 2). States comprise counties, and counties comprise wards, and wards comprise people. In short, it is strictly misleading to speak for Jefferson of government of and for the people. One must strictly speak not of American people, but of Virginian people, of Massachusettsan people, and of South Carolinian people, and so on. Speaking axiologically, the union, next to the states, was in effect a political nonentity: the latter, being polities of robust and vigorous political activity; the former, being only loosely speaking a polity and one of relative inactivity.

Figure 1

Figure 2

In sum, for Jefferson, “the union was an experiment in liberty and in no way constituted an end in its own right.” That is why Bassini asserts that the Kentucky Resolutions was Jefferson’s greatest political document.

Enjoy the interview below….

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.