A man only has room for one oath at a time. I took an oath to the Confederate States of America.” John Wayne, The Searchers

“We are going to hit the Yankees where it’ll hurt him most—his pocketbook.” Van Heflin, The Raid

“I’m sure glad I aint a Yankee.” Randoph Scott, Belle Starr

“I ain’t never been ‘round no Yankees much, thank the Lord. Knew one Yankee. Snake bit him. Snake died.” Walter Brennan, Goodbye, My Lady

Introduction

The primary purpose of this series of weekly essays is to identify films that are enjoyable, satisfying, and informative for Southern people, native or adopted. For better or worse, like it or not, movies are a major entertainment and art form of our time. Most of us will spend a good many hours in a lifetime watching them. Their stories and characters have real impact on the way we see the world.

The cinema has existed for over a century now and has produced an immense volume. No one can possibly master the field. We can only make a guide to what we have found to be worthwhile. This becomes more important as American film, like American society, sinks steadily into ever further depravity. In today’s cinema, sex, violence, perversion, and obscene language are pervasive, although tobacco smoking and Confederate flags are forbidden immoralities. We, of course, expect that families will exercise judgment as to what is or is not appropriate for the young.

The South is a large segment of American life, with a long-lived separate history and culture—if not a nation of its own then certainly the next thing to it. Its representation in American movies follows an irregular path that reflects the particular times in which films were produced. Up to the 1960’s, Hollywood had friendly tolerance and even admiration and affection for the South. Since then the main motif has been hatred and slander that casts us Southerners in the role of devils or clowns. This latter is not surprising since the South remains a reservoir of conservative, telluric connection to Western civilisation and thus an enemy to those who want to replace civilisation with an egalitarian and libertine world of their own defective imagination.

Mainstream America lacks any real cultural identity. So, it has often sought to define itself as the righteous Non-South, using the South as the hated Internal Other that is the source of all the sins that Americans fancy they are not guilty of. Or else it has tended to absorb what is favoured about the South into an artificial “America,” as in George Washington talking and acting like he was from Ohio. We are often either evil unAmericans or honourary Yankees. All of this reflects the psychological needs of Northerners, including the masters of the media, and says little about the real Southern people.

Twentieth-century American filmography is so vast that a lifetime of study could barely master it. Just the bad films about the South would take a large chapter to list. What we have done is call to attention a number of things which Southerners might watch with interest and pleasure. We have also pointed to some of the worst of the many distorted and offensive manifestations of Hollywood’s hatred of the Southern people.

The most important human wisdom is contained in stories, not in formal expositions. (Think Incarnation.) In times past people got their stories from the classics, the Bible, and the novel. Movies are now the primary story-telling medium. Stories are guides to and an expression of a people’s culture and their culture is best understood from their stories. Actors and actresses give some evidence of the state of culture because acting, if well done, is a form of cultural expression that requires some art—intelligence, grace, imagination, empathy.

Southerners are in the position of having our talents exploited and our stories filtered through the misperceptions of hostile outsiders. We are the only people of the American Empire who are persistently and safely slandered by Hollywood.

The South is immensely rich in history and human quality. We have all the ingredients for a great cinema to rival the best of other nations. There is real Southern talent enough on both sides of the camera to create a true Southern cinema. But, of course, there is no money, without which there can be no film— unlike literature, in which it is still barely possible to publish good books. If Southerners were free, actually or spiritually, to tell our own stories like the other peoples of the world, there could be a world class Southern cinema. The most beautiful of all the world’s national flags and the most rousing of all the world’s national anthems would be honoured by good people everywhere.

Symbols Used

** Indicates one of the more than 100 most recommended films. The order in which they appear does not reflect any ranking, only the convenience of discussion

(T) Tolerable but not among the most highly recommended

(X) Execrable. Avoid at all costs

NOTE: Most of the research for this book was done in the age of the DVD. “Streaming” is now becoming dominant. There should be no difficulty in finding the recommended films in that medium.

1. Hollywood and Dixie

“ . . . the play’s the thing . . .” –Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

The treatment of Southerners by Hollywood has been schizophrenic. To today’s provincially urban masters of Hollywood, whose idea of American history begins with Ellis Island, Southerners are unfamiliar and considered strange and dangerous. Films set in the South quite often portray ugly people and situations. Southern accents are invariably the sign of a villain, even in stories set in Boston, Chicago, California, or Alaska. There is a whole library of evil Southerner movies. However, at the same time, films about ordinary folks set in the South sometimes have likable characters even today. Because many Americans know from personal experience that Southerners are not cartoon villains but often honourable and agreeable people.

From the earliest days of American movies through the 1950s, almost a half century, the Hollywood portrayal of the South was to a considerable extent friendly and even admiring. The 1950’s and 1960’s continued this tradition but tended to absorb what is Southern into a generic Americanism that eclipsed its Southern aspects. This was the era when historical dramas were good on costumes but bad and silly on history. (I am reminded of a movie director in an Evelyn Waugh novel who gave John Wesley a sword and a mistress.) In the 50’s and 60’s blue-eyed starlets played Indian maidens; Ava Gardner, Elizabeth Taylor, and Natalie Wood became mulatto, apparently because they had dark hair; the avuncular Midwesterner Ronald Reagan was taken seriously as a Westerner; a coonskin cap identified a ridiculously unhistorical Davy Crockett; and “country music” singers had to disguise their Southernness by wearing pseudo-cowboy outfits.

Curiously, in the 1960’s and 1970’s the South rode high in popular culture even as the cinema began to be pervasively South-hating. The Southern persona of Burt Reynolds flourished. Southern TV shows had the highest national ratings in the age of Jimmy Carter with The Beverly Hillbillies, The Andy Griffith Show, Hew-Haw, and a little later The Dukes of Hazzard. Perhaps the difference between television and film relates to the fact that television responds to ratings while movie directors are free to indulge their own distorted view of the world.

Of course, Southern characters were only popular because they could be condescended to as inferior to Northerners. Even when good people, such TV Southerners were invariably comically backward and ignorant. Apparently in contrast to the North, where all the women are cool, poised, and beautiful Meryl Streeps and all the men are suave and dashing Tom Cruses (or cool, beautiful Meryl Streeps). Curiously, through a long period of history Southerners were noted for their gentlemanly and ladylike qualities. Anyone who has spent any time around rich Ivy Leaguers knows that any Southern “redneck” has better manners, a kindlier attitude toward strangers, more chivalry, and more personal integrity than the Northeastern “aristocracy.”

The schmaltz of the 50’s quickly gave way to the revolutionary 60’s and 70’s and a South-friendly Hollywood began to turn into a South-hating Hollywood. Since then the South has usually fared badly with Hollywood.

Until the late 60’s, our cinema—whether contemporary or costume drama, comedy, Western, or war—reflected a general baseline of Middle American values. It was not usually great art, but it was consoling entertainment and a source and reflection of a national consensus. And it portrayed with sympathy the real “diversity” of this far-flung Union—New England, the Big Apple, the South, the Midwest, and the West.

The catastrophe known as The Sixties was marked by a collapse of morals, political fanaticism and violence, multiculturalism, and the ever tighter centralised control and enforced uniformity of all phases of life by the bicoastal elite—accompanied by degradation of the American cinema. Now we have godless nihilism and self-indulgence, violence for violence’s sake, every form of sexual promiscuity, filth for the sake of filth, and “creativity” generally limited to technological fantasy, sequels, prequels, dramatization of comic books, and rip-offs of European and Japanese stories. The masters of our multicultural monoculture have little talent but plenty of power and money and our cinema now reflects their minds and souls.

This is not the whole picture, of course. There are still “independent” productions that portray actual American people and situations and that manage to come to public attention. It is possible, with some enterprise, to make a good movie. The problem is getting anyone to hear about it and get it distributed. The mass media seldom reflect anything but what works our masters want to be celebrated and the absence of those works they want to be censored or ignored. All you need to remember is the reception given Mel Gibson’s **The Passion of the Christ and Ron Maxwell’s historical epic **Gods and Generals.

There was one positive aspect to Hollywood’s turn from the happy talk of the frothy, phony 1950’s to a more mature and serious approach: more realism about the history of America and other lands. The 2004 version of **The Alamo is greatly superior to the 1960 John Wayne version in truth and drama. **The New World of 2005 is better than anything previously done by Hollywood on Captain John Smith and Pocahontas. Likewise, the 1992 **Last of the Mohicans is more vividly real than earlier versions. **The Virginian of 2000 is head and shoulders above its many predecessors. Liberation from the childish 50’s has had some positive benefits.

Like it or not, movies are the main art form of our time, the story-telling medium that reaches the largest audience and captures the attention of us all, high and low, wise and foolish. It is also true that movies, like literature and architecture, reflect something of the soul of the particular nation that produces them. If so, judging by Hollywood, we indeed need to be concerned about the American soul.

2. The Era of D.W. Griffith and Will Rogers

The Confederacy was very much present at the birth of Hollywood.

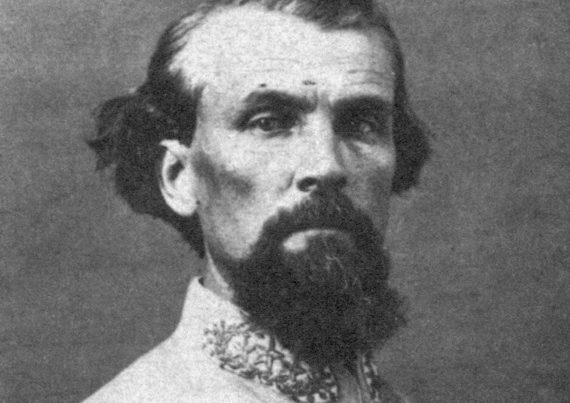

**The Birth of a Nation (1915). The great irreplaceable genius of early American cinema was D.W. Griffith of Kentucky, son of a Confederate soldier. In the Birth of a Nation he made history come aliveand showed the potential of movies as something more than an amusing novelty. Here is a rather typical description of Griffith:

“Widely regarded as the father of American film, David Wark Griffith (1875-1948) revolutionized the language of cinema and turned it from a five-cent novelty into an art form. His historical epics and Victorian melodramas achieved new heights of emotional richness. . ..” (www.Kino.com/ catalog, 2018)

After a screening in the White House, President Wilson remarked: “It is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” Birth dealt with the War Between the States and Reconstruction in a portrayal primarily centered on a Southern family and with many of the major stars of silent cinema. Although its importance can hardly be denied, the film is now out of favour, largely because of a realistic portrayal of the Southern oppression in Reconstruction that Wilson described as “so terribly true.”

Actually, there is nothing in the movie that any reasonable Northerner of the time could not have agreed with. Birth is very much a landmark of the spirit of sectional reconciliation that prevailed at the time, two years after the friendly reunion of Northern and Southern soldiers at Gettysburg. There is a generous treatment of a Northern family and an inter-regional romance. The only dubious note is a somewhat saccharine portrayal of Lincoln, but this was very much in the spirit of the time. Southerners found it useful to portray a kindly Lincoln who, if he had lived, would have avoided the worst evils of Reconstruction. There are various versions available, but the most complete seems to be the one of 192 minutes.

Griffith produced many other films of lasting interest. Although condemned as “racist,” both Griffith and the Southerner Thomas Dixon, on whose books Birth was based, were liberals for their time in the true sense of that label. They attacked the excesses of capitalism and defended working people and immigrants in an era when respectable Northerners were devoted to Big Business and ideas of Anglo-Saxon superiority.

**The General (1926). Two of the great silent classics of early American cinema have Confederate connections, and indeed both are on any list of the world’s greatest movies. One is The Birth of a Nation. The other is The General starring the inimitable Buster Keaton. It is based on a true story of a Southern railroad man who engaged in a heroic long-range pursuit of a train stolen by Yankee soldiers. (“The General” is the name of the stolen locomotive.) Keaton is the Confederate who is disappointed (as is his sweetheart) at his not being allowed to join the army because of the importance of his job. No viewer can forget the heroic aspirations, the incomparable action, humour, and the pathos of this film. Orson Welles called it the greatest comedy and probably the greatest movie ever made. (Disney did a tolerable film of the same incident as (T) The Great Locomotive Chase.)

**Judge Priest (1934). It is said that John Ford, later among the greatest of American directors, was one of the Ku Klux riders in Birth of a Nation. In Judge Priest, taken from the popular Irvin S. Cobb stories, Ford makes a gentle portrayal of people in postwar Kentucky proud of their recent Confederate cause. The star of that film was Will Rogers, certainly one of the greats of early American movies and another son of a Confederate soldier. (I once read a description of Rogers as “a Midwestern humorist.” This for the Oklahoma son of an officer in the Confederate Cherokee brigade who gently criticized Yankee ways in his pioneer radio commentaries! (As far as I know Ohio and Iowa are not noted for humour.) Rogers was undoubtedly the No. 1 American movie star and a beloved figure when he made Judge Priest. All of Rogers’s films are enjoyable and clearly if not obtrusively Southern.

**The Sun Shines Bright (1953). Ford liked Judge Priest so well that he did the same story again, perhaps even better, in The Sun Shines Bright. These films show an attractive Southern life—post-Confederate plain folks who had their foibles like all of us but created decent and pleasant communities.

**My Old Kentucky Home (1935). In his last film Will Rogers is a shrewd horse trainer who solves a long-standing family feud.