Throw thy bold banner to the breeze!

Front with thy ranks the threatening seas

Like thine own proud armorial trees,

Carolina! – Henry Timrod

June 28th is an official holiday in the state of South Carolina, although outside of Charleston, it has almost entirely been forgotten. South Carolina’s Code of Laws, 53-3-140, reads as follows:

June twenty-eighth of each year, the anniversary of the Battle of Fort Sullivan in 1776, is declared to be “Carolina Day” in South Carolina.

Known as Palmetto Day or Sergeant Jasper’s Day prior to 1875, this day marks one of the defining moments of the South Carolina’s antebellum history and would set the tone for the major role she would play in the War to Prevent American Independence —a war in which British troops, at the behest of King George III, tried to coerce 13 seceded colonies back into the British Empire.

South Carolina’s role in the first American war for independence has been downplayed, if not entirely effaced from the cannon of American History by Neo-Yankee and New South textbooks. This was not always the case. For over 100 years, South Carolina schools used various editions of William Gilmore Simms’s The History of South Carolina as its primary text for teaching South Carolina children the history of their homeland.

The following passage is taken from the 1918 edition of the Simms’s history which was edited by Mary Chevillette Simms Oliphant, Simms’s Granddaughter. It recounts the incredible story that gave rise to Carolina Day:

Arrival of the British Fleet. In May, 1776, expresses reached President Rutledge bringing the news that a British fleet under Sir Peter Parker, with a large land force under Sir Henry Clinton on board, was off Dewees Island, about twenty miles north of Charles Town bar. It was now known that the first attack upon the English provinces in America was to be against the newly made State of South Carolina. There was great excitement in Charles Town at the prospect of the attack. General Charles Lee, third in rank of the general officers of the American forces, arrived to take charge of the Southern department. President Rutledge ordered out the militia of the State, an alarm was fired and the fortifications of the city were strengthened. All the citizens went to work with enthusiasm. Works were thrown up, traverses erected across the streets, weights were taken from the windows of the houses to be cast into musket balls and the public records and the printing presses were moved out of town.

Fort on Sullivan’s Island. In January, 1776, work had been commenced upon a fort on Sullivan’s Island. This fort was not completed at the arrival of the British fleet. It was placed under the command of Colonel William Moultrie, commanding the 2nd South Carolina regiment. The fort was a square large enough to hold, when finished, 1,000 men. It was built of palmetto logs laid one upon the other. There were two parallel rows of these logs and the space between was filled with sand. The rear of the fort and the eastern side were unfinished. General Lee disapproved of any attempt to defend this island and wanted to withdraw the troops for the defense of the city. President Rutledge indignantly refused to consent to the abandonment of the island. General Lee, however, withdrew a number of the troops from this fort and also removed a quantity of powder. Defenses of the Inlet Between the Islands. Sullivan’s Island and Long Island (now called Isle of Palms) are separated by an inlet called Breach Inlet. The fleet landed Sir Henry Clinton and his land force on Long Island with the purpose of crossing the inlet and attacking the fort on Sullivan’s Island by land at the same time of the attack by the fleet from the sea. Sir Henry Clinton landed on Long Island on June 8th, and threw up works on the Long Island side of the inlet. The South Carolinians threw up works on the Sullivan’s Island side, which were manned by a force of 780 troops under the command of Colonel William Thomson. These were to resist the land force of 2,200 men. The fleet consisted of eleven ships.

The Attack on the Fort. On the 28th of June, 1776, the British ships bore down upon Sullivan’s Island and the Thunder, bombship of the British, began to throw shells upon the fort. When the fleet arrived within easy range of the fort the garrison opened fire. The leading ship, the Active, came on, however, regardless of the fire. The other ships followed and anchored in two parallel lines and a heavy bombardment of the fort was commenced. Several shells from the Thunder fell inside the fort but were buried in the sand.

As soon as the fleet commenced the bombardment of the fort Sir Henry Clinton made an attempt to cross Breach Inlet to aid in the attack. He had an armed schooner and a sloop and a flotilla of armed boats to support the troops while crossing. The flotilla advanced, but Colonel Thomson’s little force, with but two cannon, manned by men who had never fired a gun larger than a rifle, opened up a fire that raked the decks so that the men could not be kept at their posts and the flotilla turned back. The troops who were to wade the inlet at low tide were likewise driven back and subsequently offered the excuse that the tide had risen too high for them to cross.

Victory for the South Carolinians. About midday, the boats of the second line of the British fleet were ordered to pass the fort and commence an attack upon the rear side of the fort. This would have meant disaster, for, it will be remembered, this side had not been completed. Fortunately, the ships stuck upon a shoal in carrying out this manouvre. Two of the ships got off the shoal and withdrew, but the third stuck fast. The garrison of the fort directed their fire against the two largest ships of the fleet. On one of these ships was Lord William Campbell, the late royal governor of South Carolina, and Sir Peter Parker. Twice the quarter-deck was cleared of every person except Sir Peter Parker. Lord William Campbell was wounded. So great was the slaughter from the unerring fire of the garrison that at one time it was thought that the two ships would be entirely destroyed and they had decided to abandon these ships when the fire from the fort ceased.

The fire ceased because of the lack of powder. General Lee had withdrawn a part of the ammunition from the fort and it was thought that in the face of victory the defense would have to be abandoned. President Rutledge, however, succeeded in getting the necessary powder to the garrison and the defense was resumed.

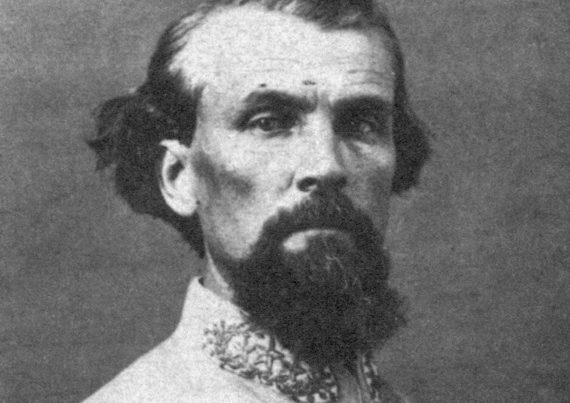

Colonel William Moultrie, the Brave Defender of the Port on Sullivan’s Island, Which Was Named in His Honor.

Some time thereafter, the flagstaff of the fort was shot away, the flag falling outside the fort. Upon this Sergeant William Jasper, of the Second regiment, leaped over the ramparts amidst heavy firing from the fleet, and, tearing the flag from the staff, returned with it. He fastened it upon a sponge staff, amidst a storm of shot and shell, and fixed it over the fort. After giving three cheers he returned to his gun unharmed.

The day ended with victory for the South Carolinians. About nine o’clock, the fire from the fleet ceased and a little later the ships slipped their cables and retired.

The total number killed in the fort was twelve and the wounded twenty-five. In the fleet we find that the two captains of the fifty-gun ships were mortally wounded, and nearly a hundred men on each ship killed. The loss of the fleet was slightly less than six to one over that of the fort. The fort, it is interesting to note, had used only 4,766 pounds of powder, while the fleet had used about 34,000 pounds.

Two days after the battle, General Lee visited the fort and thanked the garrison for their heroic defense. President Rutledge visited the garrison, also, and, taking his own sword from his side, presented it to Sergeant Jasper for his bravery in planting the flag. In honor of Colonel Moultrie, the brave defender of the fort, that structure was named Fort Moultrie.

The battle of Fort Moultrie ranks with the most decisive victories of the Revolution. The fact that the invincible British fleet had been defeated by untrained men in a little fort built of sand and palmetto logs gave a great moral impetus to the cause. Many who before had been lukewarm in their enthusiasm for independence, were now encouraged to enter whole-heartedly into preparation for the defense of the State. John Rutledge, as President of the State, had approved of manning the fort in spite of the objections of the experienced general of the American forces, Charles Lee, and Carolinians had by themselves fought the battle and won the victory. The glory of Fort Moultrie is due entirely to the valor of her own sons. By this victory the Southern expedition of the British fleet was brought to naught and war was kept from South Carolina for nearly three years.

This heroic battle is certainly an event for which the state had ample reason to celebrate and commemorate and it still is!

It is worth noting that January 1861—after secession and before joining the Confederacy—South Carolina incorporated a palmetto tree into the design of her new flag, a reference to the palmetto logs of which the fort at Sullivan’s Island was built. This along with the familiar crescent or gorget associated with the flag which flew over the Fort at Sullivan Island on that fateful day.

These symbols not only adorn the state flag, they can be found on just about anything in the “Palmetto State”—on ties, belts, shirts from casual to dress, stickers, magnets, mailboxes, coffee cups, towels, golf balls, oven mitts, you name it! Some know the origins of these symbols, but most do not.

Commemorating and, more importantly, celebrating Carolina Day—or any other Southern holiday for that matter—is one of many ways we can help folks come to understand and appreciate some of what is “true and valuable in the Southern tradition.” In fact, one would be hard pressed to find a more enjoyable way—Southerners love a good party!

I don’t know about you, but I plan to raise a glass and toast the memory of gallant defenders of Sullivan’s Island tomorrow:

To their bravery, honour, and patriotism and for the cause of liberty for which they so nobly contended!

Cheers!