As the brilliant American military victory in the Persian Gulf approaches its second anniversary, the focus has shifted from the emotions of homecoming celebrations to the seriousness of lessons learned and lessons validated. While the ingredients of victory are a combination of many factors, from logistics to training to armament, history has shown that one of the most important elements in successful combat operations is always the quality of the commander. It is the commander who decides the strategy, directs the tactics, and inspires the morale of his soldiers. To those mediocre captains of history who arrogantly relied on sheer numbers of forces to ensure success on the battlefield, the past is replete with the story of the small army, with a great leader, overwhelming numerically superior forces.

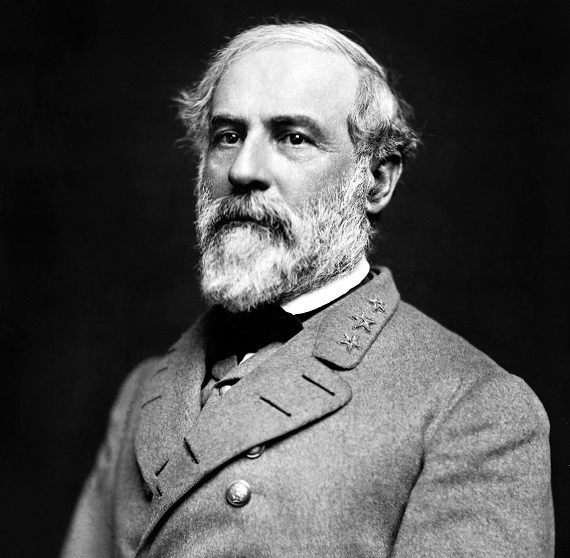

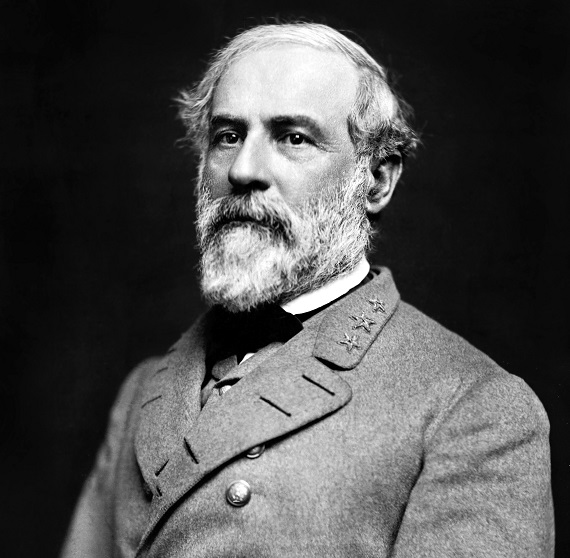

Operation Desert Storm confirmed that the American commander, General Norman Schwarzkopf, was no mediocre leader. Clearly, he had learned well many of the lessons written in the bloody ink of military history. In this context, the war also paid a magnificent tribute, albeit a silent one, to a man who is arguably the greatest military leader this country has ever produced—Robert E. Lee. Indeed, not only in the sphere of battlefield tactics, but in ensuring strict adherence to the laws regulating warfare, General Lee and General Schwarzkopf had much in common; tactical skills and ethical conduct go hand in hand in the making of a great leader.

Unfortunately, however, there are many who are unaware of the phenomenal benefits that our military has most certainly drawn from General Lee. Curiously, this was brought out by the battle in the Persian Gulf. When reporters asked General Schwarzkopf which military leaders he most admired, Schwarzkopf, as expected, turned to the War Between the States for his examples. What was totally unexpected, however, was that he ignored the obvious choice of General Lee. a choice that other modern American commanders such as General William Westmoreland (from the Vietnam era) had easily made, and instead cited General William T. Sherman as one of his heroes! The United States of America was fortunate that both General Schwarzkopf and the forces under his command emulated the tactics and humanity of the Confederate General and not the Unionist.

An unspoken tribute to General R.E. Lee was particularly evident in regard to the grand strategy used by the American commander in the Gulf. As General Schwarzkopf held his “victory” press conference and explained the concept of the overall operation in the defeat of the Iraqi forces, it was obvious that not only had he been able to successfully apply the lessons and experiences of his own career, but that he had drawn heavily from the wisdom of General Lee.

To the serious student of American history, Schwarzkopf’s celebrated “Hail Mary” flanking movement to the west of the enemy strongly echoed from another time and place. While no two wars are ever alike, and each commander’s actions must be evaluated in terms of their unique circumstances, the basic tactics employed in the “hundred hour” ground war were undeniably similar to those used by the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Time after time Lee executed magnificent flanking movements at such battles as Second Manassas (1862), Chancellorsville (1863), and the Wilderness (1864). In short, the ground phase of Operation Desert Storm was vintage Lee—fix the enemy in place and hit him suddenly and heavily in the flank. The heart and soul of Lee’s superior strategy was based on surprise and economy of force, the same key elements superbly utilized in Operation Desert Storm.

Lee as Role Model

To contend that America’s military leaders still concentrate on the military campaigns of General Lee is, of course, no revelation to most senior officers in the armed forces. Even the United States Navy acknowledges the leadership abilities of Lee, studying and publishing at the Naval War College the works of scholars who have devoted their entire lives to exploring the person and legend of Lee. As for Lee’s most natural constituency, the ground commanders, one need only take a cursory tour of the Army War College in Pennsylvania to confirm their commitment to studying the War Between the States in general, and R.E. Lee in particular. Battle scenes from the bloodiest war in American history hang from almost every hall in the institution. In a recent U.S. Army War College publication concerning two of Lee’s classic victories, the authors confidently challenged modern officers to learn from and appreciate the genius of Lee and his corps commander T. J. “Stonewall” Jackson. In the preface they note: “Lee and Jackson did not see themselves as old soldiers; they considered themselves modern soldiers, and today’s officers will quickly learn to identify with them (emphasis added).”

Lee’s Impact on the American Military

Apart from being the most enduring conflict in the nation’s psyche, the War brought into focus the extraordinary genius of General R. E. Lee. A genius so phenomenal that his impact upon the armed forces of the United States is still felt over a hundred and twenty years after his death! This is not surprising, however, when one considers that even before the outbreak of the War, Lee’s military value was already firmly established in the young nation.

General Winfield Scott, commander of the American forces during the Mexican War (1846-48), noted on many occasions that that war was won due largely to the efforts of, then, Captain Robert E. Lee. Captain Lee had made such an impression on Scott that thirteen years later (in 1861), when asked about the best officer in the U.S. military, he promptly replied: “I tell you, sir, that Robert E. Lee is the greatest soldier now living, and if he ever gets the opportunity, he will prove himself the greatest captain of history.”

President Abraham Lincoln was also well acquainted with Lee’s military acumen. In April 1861, before Colonel Lee (serving in the 2nd U. S. Cavalry) had to decide between Virginia and the Union, Lincoln eagerly tendered to Lee the supreme command of all Union forces in the field. If accepted, Lee would be second only to General Scott, who was then the General-in-Chief of the Federal forces.

Taken to the mountain top of temptation and offered what every soldier dreams of—fantastic success and fame—Lee maintained his loyalty to his state and family, thereby reflecting to the world a glimpse of his incredible integrity. A product of Southern aristocracy, honor and duty were more important than fame; he could not draw his sword against his native state. W. T. Sherman would later write of Lee, “His Virginia was to him the world ….”

At the conclusion of the War Between the States, military leaders throughout the world quickly recognized the incredible battlefield accomplishments of Lee. British, Prussian, and French officers, renowned in their own right, expressed only the highest regard for General Lee. These included Colonel Chesney, Lord Roberts, Colonel Henderson, Von Moltke, Bismarck, Von Borcke, Colonel Scheibert, Major Mangold, and many others. The great British officer, General Garnett Joseph Wolseley, had observed Lee at first hand during the War and called him a genius in the art of warfare, “being apart and superior to all others in every way, a man with whom none I ever knew and few of whom I have read are worthy to be classed.”

While the Virginia of the Old South has long since faded, in the decades that have passed and to this day, Lee’s name has only increased in brightness, until he illuminates the pages of military doctrine as perhaps no other soldier in American history. It was from France, in the 1870s, that world-wide recognition of Lee as a great “soldier, gentleman and Christian” first began. By the first decade of the twentieth century, Britain had also become totally enthralled with Lee, due in part to the great English writer Henry James. The Canadians, who had always been sympathetic to the South, quickly expressed their high regard for General Lee. By the time Lee died, in 1870, the Montreal Telegraph was able to say: “Posterity will rank Lee above Wellington or Napoleon, before Saxe or Turenne, above Marlborough or Frederick, before Alexander, or Caesar …. In fact, the greatest general of this or any other age. He made his own name, and the Confederacy he served, immortal.”

Indeed, in the history of the United States, there has never been an officer who inspired such great devotion and trust in his soldiers as did General Lee. This fact was beautifully illustrated in an incident just before the surrender at Appomattox when Lee turned to Brigadier General Henry Wise and asked him what the army and country would think of him once he surrendered. General Wise, a former governor of Virginia blurted out, “General Lee, don’t you know that you are the army …. [TJhere is no country. There has been no country, for a year or more. You are the country to these men.”

Arguably, Lee contributed more than any other single man in setting the very bedrock for some of the most outstanding and valuable attributes of American military power. A bedrock so strong that today, when asked to identify the most notable characteristics of the U.S. military, one can expect the worldwide response to literally echo his signature: (1) the superior tactical abilities of the combat leaders, and (2) the civilized conduct of Americans in war.

That the American military establishment has proudly maintained its reputation for sound military tactics as well as an unmatched sense of humanity is well known. What is not as well advertised is the man most responsible for all of this. Perhaps it is the passage of time that conceals his name. More likely, however, it must be attributed to the prejudice of those who are loath to find anything positive associated with the Southern cause—a cause that most Americans still do not understand.

In spite of the fact that their greatest champion is often overlooked, “Leeonian” tactics and civility have become ingrained into the character of the U.S. military establishment. Although these qualities certainly existed before the emergence of Lee the general, it was his genius and humanity that epitomized and translated them into the very fabric of subsequent American military doctrines. For this reason, any analysis of the U.S. military, either in terms of tactics or comportment with the law of war, that ignores the amazing contributions of General Lee can never be more than a fraction of the truth. He, more closely than any other officer, is most qualified to project the American standard of behavior in these areas.

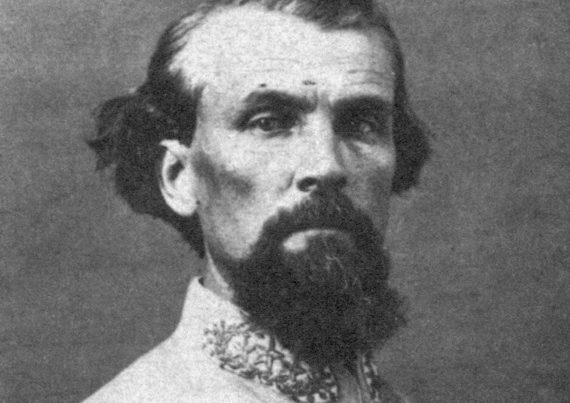

William T. Sherman

When General Schwarzkopf listed General Sherman as among those whom he most admired from history, many misunderstood the reasons associated with that choice and hence, the efficacy of such a statement. In the minds of most knowledgeable Americans, particularly in the South, the name of W. T. Sherman is immediately associated with a most heinous array of war crimes.

This, of course, was not the quality that General Schwarzkopf sought to embrace when he listed Sherman as one of his heroes. Was it then the tactical side of Sherman that won Schwarzkopf s respect?

Few historians rank General Sherman among the brilliant. Most writers believe that he was far too cautious when conducting war against sizable concentrations of enemy soldiers. “As a consequence he tended to hold back both in the employment and deployment of his forces. This in turn either cost him defeats, as at Missionary Ridge, or else lost him the fruits of victory, as at Jonesboro.”

As a military commander, Sherman was at best only average. However, compared to the vast majority of Union general officers, who were notoriously incompetent, Sherman looked fairly capable. His mainstay was his tenacity, not his imagination. Tenacity, however, can do great things when juxtaposed with a tremendous military might, such as was furnished to him by the industrialized North. Sherman could systematically conduct his version of “total war” at will.

After burning the entire city of Atlanta to the ground, Sherman set out with over 62,000 Federal soldiers; not to engage Confederate combat forces but to “make Georgia howl.” The only Confederate military forces that could have opposed Sherman had left Atlanta and headed north into Tennessee. Apart from Rebel cavalry to harass his flanks, or small local home guards consisting of old men and boys, General Sherman faced no significant military opposition until he reached North Carolina. Sherman wrote: “Until we can repopulate Georgia, it is useless to occupy it; but the utter destruction of its roads, houses, and people will cripple their military resources. I can make this march and make Georgia howl.”

Tragically, the only persons who “howl” under such brutal activities are always the defenseless civilian population, primarily women and children. Although Sherman issued “official” orders that prohibited the trespass of all dwellings, required the leaving of reasonable provisions for families who were forced to provide food, and even prohibited the use of profane language, in reality none of these orders were actually enforced. The soldiers were allowed to rob, pillage, and burn in a swath of horror that, from wing to wing of his forces, extended almost 60 miles in width!

As the Union army approached their homes, defenseless Southern civilians understood the approaching terror. In the distance, they could see the pillars of smoke by day and the fires by night. If Sherman did not order the rape and other physical abuses that accompanied his campaign of terror, he, as the commander of the army, must share responsibility for these additional crimes. While physical abuses were widely reported, the issue of rape remains less certain. Because of the social stigma attached, rape was a crime seldom discussed in nineteenth century America; victims often kept the crime to themselves. While it was probably less widespread than some might allege, there are documented cases of Sherman’s forces raping black and white Southerners.

Boasting of his wholesale looting and burning through Georgia, General W. T. Sherman telegraphed his superior, General U. S. Grant: “I sincerely believe that the whole United States, North and South, would rejoice to have this army turned loose on South Carolina, to devastate that state in the manner we have done in Georgia.” Because South Carolina was the first Southern state to secede from the Union, Sherman felt that the citizens of the state should be made to suffer in a special manner. Consequently, Sherman thoroughly devastated South Carolina. A noted Northern journalist, John T. Trowbridge, traveled through South Carolina just after the War ended and recorded the sight that greeted him. “No language can describe, nor can catalogue furnish, an adequate detail of the wide-spread destruction of homes and property. The Negroes were robbed equally with the whites of food and clothing. The roads were covered with butchered cattle, hogs,mules, and the costliest furniture….”

Later, as Sherman headquartered in the finest mansion in Savannah, he again corresponded with Grant concerning his upcoming march through South Carolina. As if attempting to shed all responsibility for controlling his army Sherman said, “the whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreak vengeance upon South Carolina. I almost tremble for her fate, but I feel she deserves all that seems in store for her.”

The Law of War During the War Between the States

Granted that the modern international rules regulating the conduct of armed forces during combat, codified in the 1949 Geneva Conventions, did not exist during the War, Sherman certainly violated the well established customary prohibitions of his day in addition to the much praised Lieber Code.

Francis Lieber, a German international law scholar and professor at Columbia University, was asked by the Federal authorities to draft a code for the conduct of war on land. Promulgated as, “Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field,” it was issued on April 24, 1863. The Lieber Code consisted of 157 articles. The Southern forces adopted their own code of conduct for land warfare in 1861: “Articles of War, Regulations of the Army of the Confederate States.” In addition, James A. Seddon, the Confederate Secretary of War, pledged to abide by most of the substantive provisions of the Lieber Code. This code, coupled with the existing customary obligations, absolutely prohibited the larceny, vandalism, or indiscriminate burning of civilian property, as well as all associated crimes of violence against civilians. Article 47 of the Lieber Code provided that:

Crimes punishable by all penal codes, such as arson, murder, maiming, assaults, highway robbery, theft, burglary, fraud, forgery, and rape, if committed by an American soldier in a hostile country against its inhabitants, are not only punishable as at home, but in all cases in which death is not inflicted, the severer punishment shall be preferred.

To be sure, a handful of Union officers and soldiers assigned to Sherman did display military discipline, but the vast majority of Sherman’s troops, intent on booty, soon discovered that the chain of command made little effort to protect civilians or their property. Early in the “march,” some subordinate commanders, such as General Oliver Howard, dutifully informed Sherman that the soldiers were committing “inexcusable and wanton acts.” While still marching through Georgia, well before the most barbarous atrocities were committed, General Howard even issued his own orders:

It having come to the knowledge of the major general commanding that the crime of arson and robbery have become frequent throughout this army, notwithstanding positive orders both from these and superior headquarters having been repeatedly issued … it is hereby ordered: that hereafter any officer or man of this command discovered in pillaging a house or burning a building without proper authority, will upon sufficient proof thereof, be shot.

Despite such “official” directives that threatened death by firing squad for any form of pillaging, not a single Union soldier was ever executed. The obligatory wink at the “law” had been given. “[H]is men knew he [Sherman] would understand if they went beyond the orders. A great deal of unauthorized and individual looting went on as the army ripped across the state, and it went unpunished.” Accordingly, bands of roaming marauders calling themselves foragers or “Sherman’s Bummers” engaged in indiscriminate plunder upon the defenseless civilian population.

Sherman’s only attempt at defending his crimes occurred over the burning of Columbia, South Carolina. Despite numerous eyewitness accounts to the contrary, Sherman always denied the burning of Columbia, blaming it on the retreating Confederate cavalry. In defending his atrocities, General Sherman did not have the sophistication to conceal his crimes under the guise of military necessity. As provided in Article 44 of the Code, destruction of private property was allowed upon the order of an officer in the case of military necessity. Although the exception was worded in the negative, “all destruction of property not commanded by the authorized officer … are prohibited …,” it was in no way meant to be broadly construed. If Article 44 allowed the means for an officer to order an otherwise illegal act, Articles 14 through 16, by setting out strict definitions of the term military necessity, certainly limited his ability to issue such commands. Article 14 held that military necessity “consists in the necessity of those measures which are indispensable for securing the ends of the war, and which are lawful according to the modern law and usages of war.”

Anticipating that most cases of military necessity would involve the taking of food stuffs from the local population, Article 15 of the Lieber Code did allow for the “appropriation of whatever an enemy’s country affords necessary for the subsistence and. safety of the army …. (emphasis added).” Sherman, however, paid little attention to the code. In twisted logic based on pure vengeance, he openly and intentionally targeted innocent civilians in order to make them suffer for having supported the Confederacy, not to feed his troops. Claiming that his barbarous machinations had a bright side, that they might somehow induce the civilians to sue for peace, Sherman freely admitted: “If the people [civilians in the South] raise a howl against my barbarity and cruelty, I will answer that war is war, and not popularity-seeking. If they want peace, they and their relatives must stop the war.” By his own admission, Sherman purposefully violated Article 16 of the Lieber Code:

Military necessity does not admit cruelty – that is, the infliction of suffering for the sake of suffering or for revenge, nor of wounding or maiming except in fight … nor wanton destruction of a district. It… does not include any act of hostility which makes the return to peace unnecessarily difficult.

Finally, the popular but erroneous contention by some modern writers that “General Sherman’s march of devastation … during the American Civil War may have been viewed as lawful tactics at the time” is simply a twisted manifestation of “victor’s justice.” The adoption of the Lieber Code as an official military order made the Code absolutely binding on all Federal soldiers, particularly the officers who were solemnly charged with upholding the laws.

Total War

In today’s setting, had General Schwarzkopf followed Sherman’s example of “total” war, he would not only be guilty of numerous war crimes, but the army he commanded and the nation he represented would have been subjected to the scorn and ridicule of the ‘ entire civilized world. Even by the somewhat less rigid standards of his own day, General Sherman left I the civilized world nothing worth emulating. Obviously, however, in stark contrast to his opponent Saddam Hussein, General Schwarzkopf strictly adhered to both the spirit and the letter of all aspects of the law of armed conflict. With the wholesale looting, hostage taking, murdering, torturing, raping, and environmental destruction visited upon Kuwait, it was Saddam Hussein who carried General Sherman’s notion of “total war” to unspeakable extremes.

Furthermore, it would be inconceivable that the American government would long tolerate abuses of this critical rule of law, particularly abuses that were command directed. Under the provisions of the Geneva Conventions, each nation is under obligation to search for persons alleged to have committed war crimes, to investigate the allegations, and to prosecute or extradite those so accused.

Unfortunately, Sherman’s conduct was not shocking to the Lincoln Administration, regardless of the rules breached. On the contrary. Lincoln was well pleased. Then again, the same authorities that had earlier condoned the forced evacuation of every human being in most of the border areas of western Missouri and the burning of every single home (General Order No. 11), could hardly be expected to flinch over Union atrocities in the heart of Dixie.

Thus, when Sherman quipped that “War is hell,” it was only he, by his barbarous acts, that made it so hellish. Sherman’s tactic, to assert that because war is utterly repulsive that one need not abide by rules, is as old as it is fallacious.

Conclusion

The antithesis of Sherman, General Lee is not only remembered as a military genius, but he is equally praised, North and South, for his careful adherence to the laws of war, particularly in the protection of the property and person of civilians. Lee never subjected the Northern civilian population to the terror and horror that was visited upon his own people. On the other hand, to those who knew Lee, it could have been no other way.

In April 1861, when Lieutenant General Scott received Lee’s resignation from the U.S. Army in order to offer his services to the Southern cause, Scott expressed the greatest regret. A witness, however, noted that General Scott was consoled knowing that he “would have as his opponent a soldier worthy of every man’s esteem, and one who would conduct the war upon the strictest rules of civilized warfare. There would be no outrages committed upon the private persons or property which he could prevent.” Clearly, even before their codification in the Lieber Code, Scott understood, as did Lincoln, Sherman, and Grant, what the customary international rules regarding civilized conduct in war required of them.

On both of his campaigns into the North, Lee conducted his army impeccably, punishing all those soldiers arrested for larceny of private property. Fully realizing that Union forces had wantonly razed civilian homes and farms in the neighboring Shenandoah Valley, Lee nevertheless kept close rein on his soldiers. Lee wrote:

No greater disgrace can befall the army and through it our whole people, than the perpetration of barbarous outrages upon the innocent and defenseless. Such proceedings not only disgrace the perpetrators and all connected with them, but are subversive of the discipline and efficiency of the army, and destructive of the ends of our movement.

Although some Southerners have criticized Lee for not authorizing lawful reprisals in order to deter Federal violations in the future, General Lee firmly believed that reprisals were not the answer. Responding to a letter from the Confederate Secretary of War regarding possible Confederate responses to Union atrocities, Lee reiterated his position in the summer of 1864:

As I have said before, if the guilty parties could be taken, either the officer who commands, or the soldier who executes such atrocities, I should not hesitate to advise the infliction of the extreme punishment they deserve, but I cannot think it right or politic, to make the innocent … suffer for the guilty.

With Americans fighting Americans, Lee knew that the long-term effects of engaging in reprisals would not be profitable for the nation or the South. In this, he was undoubtedly correct; Lee’s strict adherence to the rules regulating warfare, coupled with his firm policy of prohibiting reprisals, contributed greatly to the healing process of the War.

One of the driving forces that created the legend of Lee, the ultimate gentleman, was his unmatched sense of humanity. “Lee was the soldier-gentleman of tradition, generous, forgiving, silent in the face of failure…a hero of mythology.” No matter how great the temptation for legitimate reprisals, a concept well recognized in international law, R.E. Lee would not stoop to the level of his enemies.

This is one of the reasons he has been called the “Christian General,” (aside from the fact that Lee believed in salvation through faith alone in Christ alone.) as reflected in his address to the troops as they marched into Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg campaign of 1863: “It must be remembered that we make war only on armed men, and that we cannot take vengeance for the wrongs our people have suffered without lowering ourselves in the eyes of … Him to whom vengeance belongeth.” Instructing his officers to arrest and punish all soldiers who committed any offense on the person or private property of civilians, he reminded them that “the duties exacted of us by civilization and Christianity are not less obligatory in the country of the enemy than in our own.”

In contrast, Sherman’s atrocities simply sowed the seeds of hatred for generations of Southerners; a common epitaph for those who commit war crimes. His assumption that he could terrorize the South into submission by devastating the farms and towns was totally fallacious. “Although the havoc wreaked by Sherman’s hordes contributed to the Confederate defeat, this contribution was so indirect and ambiguous that it did not justify militarily, much less morally, the human misery that accompanied and followed it.”

The contention that violations of the law of war are necessary in an “ends justifies the means” analysis is fundamentally inaccurate. Aside from the obvious issue of morality, violations are most often simply an unwise waste of military resources. As the pragmatic Prussian soldier and author, Karl von Clausewitz, observed: “If we find that civilized nations do not … devastate towns and countries, this is because their intelligence exercises greater influence on their mode of carrying on War, and has taught them a more effectual means of applying force …”

One noted historian has described the true legacy of W. T. Sherman:

Sherman must rank as the first of the modern totalitarian generals. He made war universal, waged it on the enemy’s people and not only on armed men, and made terror the linchpin of his strategy. To him more than any other man must be attributed the hatred that grew out of the Civil War.

In the context of Operation Desert Storm, it is abundantly clear that the only quality that General Schwarzkopf took from Sherman was his reputation for ferocity. General Schwarzkopf related on numerous occasions that he hated war and all that it brought. He also pointed out, however, that “once committed to war then [one should] be ferocious enough to do whatever is necessary to get it over with as quickly as possible in victory.”

The difference, of course, was that Schwarzkopf, in lawful combat, directed his ferocity towards legitimate military targets of the enemy, while Sherman illegally directed his ferocity towards innocent and helpless civilians. Obviously, it was in this limited analogy to the concept of “ferocity” only that General Schwarzkopf paid any respect to William T. Sherman. From both a military as well as a legal and moral perspective, General Schwarzkopf was not advocating that the United States military should find anything positive associated with General Sherman.

Whether judged in the light of tactics or of moral conduct, the actions of the American military in the Gulf War reflected the impact of Lee, not Sherman.

Gauged by these two factors, Operation Desert Storm was not a place where lessons were learned but a place where lessons were validated. In turn, with this validation of the magnificent ability and character of America’s fighting forces, there must come an appropriate tribute to Robert E. Lee.

For great armies are neither created nor sustained by accident. To a large degree, great armies are maintained by those officers who understand and then are able to apply the lessons of military history. In this respect, no officer can truly be called a professional without a firm commitment to the moral and ethical rules regulating combat. Quite naturally, this objective

requires constant training as well a comprehensive understanding of one’s moral roots.

This article was originally published in the 3rd Quarter 1992 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.