Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind was enthusiastically received when it was published but it has run afoul of the socio/political trends of recent years. Consequently, society’s censors want the book banned. Throughout history there have been political and sanctimonious types who tried to restrict what the populace is permitted to read, but in our generation these types seem to be proliferating. Among their forms of censorship is imposing restrictions on how the past is allowed to be described.

Some of the basic rules that Gone With The Wind violates are: Reconstruction must be depicted as a benevolent endeavor that implemented far-reaching humanitarian social improvements. Slaves should not speak with black dialects of their time and house slaves must not be shown having amiable interactions with their master’s family. White antebellum Southerners should not be depicted as having sympathetic attributes. Portrayals of General Sherman’s march through Georgia must indicate that it was necessary to bring the War to an end and that only military and industrial sites were harmed.

The proposed censorship of GWTW brings to mind the psychological process described as “reperceiving.” For example, adults who are troubled with memories of an unhappy childhood or other unpleasant events from the past are counseled to “reperceive” those memories, e.g., to remember the past in a more gratifying way. A clinical psychologist expressed it this way: “… the process of revisioning the past is mostly about reperceiving it in a way that helps correct present deficiencies in your self-concept.”

It is one thing for an individual to alter how they perceive unpleasant memories, but “revisioning the past” of a society composed of disparate groups is quite different. If a member of one of today’s protected classes objects to the way the past is portrayed, even if it is historically accurate, there are often attempts to censure the offensive portrayal. But in a “multicultural” society, each culture is supposed to accommodate the ethnic differences of other cultures. Shouldn’t this rule also apply to Southern culture and Miss Mitchell’s classic novel?

It is not only GWTW that has fallen victim to this coercion. Dramatizations of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice have modified the characterization of the Jewish moneylender, Shylock, to avoid perceptions of anti-Semitism. Also, to prevent potential offensiveness, The Hunchback of Notre Dame has been re titled The Bellringer of Notre Dame.

In 2014, a Harris Poll indicated that, after the Bible, Gone With the Wind was America’s favorite book; selling over 30 million copies, translated into various languages, and issued in over 40 countries. Published in 1936, it was deemed the year’s best novel by the National Book Awards, and it won a Pulitzer Prize the following year – This was long before organizations began awarding writing prizes for political rather than literary reasons.

The book’s author, Margaret Mitchell, became as much a household name as her characters, Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler. Margaret’s father, Eugene Mitchell, a prominent Atlanta attorney, was born the year after Reconstruction began. The history of the War Between The States and Reconstruction became an obsession with Eugene Mitchell and he immersed himself in the details of those historical events, becoming one of the founders of the Atlanta Historical Society. – Growing up in such a family, in the Atlanta of the early 1900s, Margaret also became something of an authority on the effect the War and Reconstruction had on Georgia.

After several years as a journalist, Margaret Mitchell left the Atlanta Journal, and was soon bedridden with a broken ankle that was slow to heal. During her long convalescent period, she began writing her novel, using the events of the War and Reconstruction in Georgia as a background for a romantic intrigue. Writing a novel was essentially an antidote for boredom, but as the plot line and characters emerged, Margaret began thinking about having it published. Primarily as a result of her scrupulous research into historical events, it took nearly a decade for her to complete GWTW. Even after it was accepted for publication, she spent another six months verifying the accuracy of historical details included in the book.

Although Mitchell was writing a novel, she and her family felt it was important that the effects of the War and Reconstruction on the South, especially Georgia, should be recorded faithfully. They believed that with the passage of time, the nation would interpret the actual events with hindsight, their interpretations overly-influenced by the contemporary generation’s political sentiments. I don’t think Miss Mitchell, or her family, realized how prophetic their concerns were.

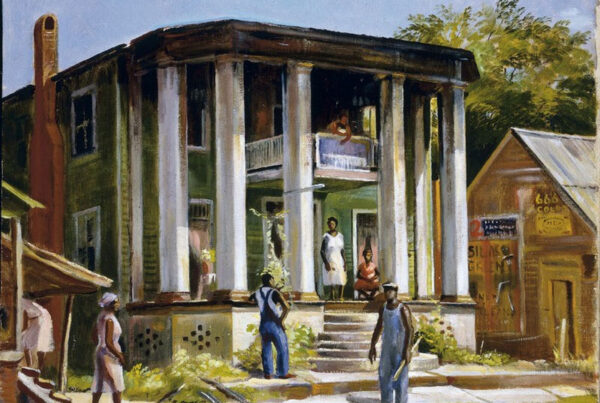

The National Park Service proposes to designate famous Reconstruction sites as national landmarks in order to tell the story of Reconstruction. According to the Park Service, “Historians’ understandings of Reconstruction changed dramatically over the course of the 20th century, but current scholarship on the period has been slow to enter public consciousness. Discredited legends of ‘carpetbaggers,’ ‘scalawags,’ and other corrupt individuals and practices often stand in place of historical fact.” So, visitors to these Reconstruction sites will be informed that the existence of “carpetbaggers, scalawags, and other corrupt individuals” are not supported by contemporary historians . They are simply “legends” – exaggerated characterizations of a prior generation, fictionalized in Gone With The Wind , a book that portrays aspects of Reconstruction unfavorably. We are not surprised by the National Park Service’s politicizing of historical sites. Civil war battlefields were previously usurped to proselytize about the evils of slavery in the South.

Miss Mitchell’s novel also conflicts with an action by the Georgia Historical Society. The Society recently erected a monument in Atlanta to commemorate General Sherman’s march through Georgia. The brief commendation inscribed on the monument contains this language: “Contrary to popular myth, Sherman’s troops primarily destroyed only property used for waging war — railroads, train depots, factories, cotton gins, and warehouses… Sherman’s “hard hand of war” demoralized Confederates, hastening the end of slavery and the reunification of the nation.” There is a mistaken impression that the Georgia Historical Society is composed of historians. Although the Society promotes Georgia history, its voluntary membership consists of of civic leaders and local citizens who want their State presented in the way that best promotes tourism and attracts industry. Hence the conciliatory memorial to Union General Sherman.

The Association of Writers & Writing Programs removed a writer from the planning committee for next year’s annual meeting because she has been posting the text of the novel “Gone with the Wind” on Twitter. The Association stated “We acknowledge her right to exercise her creativity, but we find her work to be, at best, startlingly racially insensitive, and, at worst, racist.”

The banned writer protested that she doesn’t typically comment on her “artistic work”, but is making an exception to note her belief that “Gone with the Wind” is a “profoundly racist text.” She maintains that “The book’s true love story is not between Rhett and Scarlett, but white America’s affair with self,” and she wanted to demonstrate “the whiteness behind the blackface” of the 1936 novel. (Whatever that means.)

The banned writer’s Twitter was also deemed offensive because it included a picture of Hattie McDaniel in her costume as “Mammy” in David Selznick’s award winning film version of GWTW. Miss McDaniel won an Academy Award for her acting and, in her triumphal acceptance speech, reminisced about her role in GWTW, stating that she tried to be “always a credit to my race.” Oscar Polk, who portrayed the slave Pork said that black actors in GWTW ” should be glad to portray ourselves as we once were because in no other way can we so strikingly demonstrate how far we have come in so few years.”

The literature police agree that characters like Mammy and Pork have some basis in fact, but insist that their portrayal shouldn’t be allowed because it could be demeaning to blacks. This is a strange judgment but typical of the PC brigade: Aren’t they saying that blacks should be be shielded from unpleasant subject matter because they lack the intestinal fortitude to cope with it? This opinion would seem to be insulting to blacks. On the other hand, no one claims that the fictional character, Scarlett O’Hara, should not not be permitted because she is demeaning to Southern women.

Not only do self-anointed censors resent Margaret Mitchell’s depiction of Mammy and Pork, they do not think that a benign relationship between the O’Hara family and its slaves should be allowed. But Mammy and Pork are house slaves, not field slaves, and they conduct themselves in the same manner as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s house slave, Uncle Tom. Margaret Mitchell is faulted for her depiction of house slaves, whereas the New Englander, Mrs. Stowe was praised for her’s. So it seems that what is objectionable is not the way slaves were delineated, after all both stories were set in slave states in the 1800s, but it is the author’s reason for writing that is faulted.

To reach as much of the public as possible, Mrs. Stowe created one-dimensional characters – her defenders prefer the term “allegorical” characters. (Simon Legree is too evil and Uncle Tom is too noble.) But the technique worked for Stowe’s purposes, and it is true that her novel had a profound effect of the country’s rank and file, as well as its leaders. Because Stowe wrote for the “right” reasons, the literary sanitizers have largely avoided criticizing her portrayals of slaves.

Margaret Mitchell never pretended that she was motivated to write Gone With The Wind as a result of high moral principles. She chose to set her novel in the antebellum South because it was a time and place that she well understood. Her celebrated characters breathe with real life – their behaviors and dialects are faithful to the time and place – and her novel is a special literary creation that continues to attract readers and impress literary critics. Mitchell began writing her 1000 page book in the 1920s and completed it in the 1930s. It was a time when the public was still capable of reading long books – years before television and other electronic distractions diminished the attention spans of Americans.

I suspect that much of the criticism of GWTW comes from persons who have only seen the film but haven’t read the book. I confess that it was only a few years ago that I finally got around to reading it. My expectation was that it would not compare favorably to the other classic works of literature but I was wrong – it is a literary work of exceptional quality – more than just a romance novel, an historical novel.

It enjoys tremendous popularity in foreign nations that have undergone the ravages of war. Its Russian translator said of GWTW : “The whole thing happened in Russia…we were survivors of war, like Scarlett, and this novel was ringing a lot of bells for us. We saw the ravages…the fires…the pilloried villages …the poverty and the hunger. Gone With The Wind is considered in Russia as the American War And Peace.”

The late columnist, Joe Sobran, considered Gone With The Wind to be The Great American Novel. Writing about the book, Sobran said: “Since the late 1940s liberal critics have derided it for creating a falsely glamorous picture of the Old South … the moonlight-and-magnolias image of the Confederacy … Yet GWTW is anything but a glamorization of the Confederacy; just the opposite. The story unfolds amid bitter war and vindictive Reconstruction. Its hero and heroine are a pair of scalawags who share none of the illusions of their compatriots …The slaves have both dignity and individuality: Mammy and Uncle Peter are quite unafraid to tell Scarlett off … GWTW is a superb and mature novel, one that makes everything Hemingway wrote about war and manhood, not to mention women, seem puerile by comparison.”

Gone With The Wind is indeed a great American novel and it must not be banned or censored.