In the book The Mystery of the Wonder-Worker of Ostrog, the main character, Mladjen, a fictional representation of the modern Serb uprooted from his traditions by the lingering effects of Communism (who is very much akin to many of those inhabiting the New South, shorn of so much of their past by the all-too-present effects of Communism’s alter-ego, Capitalism), has a searing encounter at an abandoned church in the countryside:

Suddenly, a piercing cry rang out, resounding clearly through the church as though in a mountain cave and rousing him from his reverie. He let go of the window bar and retreated a few steps from the church. He looked at the sky and saw a huge eagle circling above the village with mighty flaps of its wide wings. Shielding his eyes from the sun with his hands, the young man drank in the bird’s unrestrained and powerful, yet peaceful movements as it cruised overhead. Suddenly, the words of a poem came to him and he cried out on impulse:

O my brother, thou imperial eagle,

Would that I could but once cruise the heavens with thee!His voice, although not very deep, was nonetheless quite strong and it whistled like an arrow around the hills, coming back to him in a resounding echo. When finally he lowered his eyes, a strange dizziness seized him and he swayed and staggered in the direction of the steep slope, barely managing to keep himself from falling down. A heavy mist seemed to be descending from nowhere, covering everything around him. It seemed as though the clouds had come down and had released an unbearably foul-smelling substance that quickly spread all around. When his vision cleared a little, he no longer saw the rocky, in its own way, idyllic landscape. As though transported in time, he slowly took in the horror and deadly silence of a real-life bloody battlefield after a violent clash of armies. Through the veil of smoke rising from the bushes and the jagged rocks he saw a sight that made his blood freeze in horror. All around the slopes of the rocky hills, in the hollows and crevices, on the road and below, and high up in the crests of the hills, wherever his eye could see, the young man saw thousands upon thousands of human corpses and dead horses lying in heaps, covered with flocks of black vultures whose greedy cries were the only sound he heard in the silence of this shadow of death which had come down upon the earth. He saw broken and bloodied battle banners, white ones with a red cross in the middle and green ones with a crescent moon and star on them, round black hats with emblems of Serbian insignia on them and fezzes, curved swords, rifles and barrel guns. He was witnessing the bloody aftermath of one of the countless battles that had taken place over the centuries on the mountain passes near the sacred shrine of Ostrog between martyred Christian warriors and the armies of the ungodly.

He broke out in a cold sweat and he closed his eyes, but could still feel the terrible stench that made his stomach turn. In a violent rush of nausea he collapsed to the ground and curled up in a ball and, pressing his face to a flagstone, remained for some time in this position without moving. When at last he raised his head again, the nightmare vision had vanished and the calm of a late spring afternoon reigned all round once more. Feeling considerably calmer himself, he stood up slowly, brushing off the dirt from his trousers and straightening his shirt. Then, remembering the eagle, he scanned the sky searching for it. The sky, illumined by the crimson rays of the setting sun, was clear and calm. The eagle had flown away (Protopresbyter Radomir Nikchevich and Vesna Nikchevich, trans. Ana Smylyanich, Svetigora, 2003, p. 51).

So many people want their lives to matter, to feel meaningful, to believe they are part of some great, unfolding drama. Hollywood does a good job of feeding this desire and also of trying to satisfy it, in ways that are ultimately futile: mainly, that is, by drowning its patrons in a never-ending stream of its ‘epics’: Star Wars, The Avengers, etc.

What Southerners do not realize is that they are part of a much more real, and much more meaningful, drama than they are aware of. Burning memories and experiences like those of Mladjen are just beneath the surface of every Southerner’s life.

How? Why?

Because the war for the South never ended. Yes, the bullets stopped flying long ago, but the effort to eradicate the traditional Southern way of life has continued.

In light of this, everything takes on new significance. Every word and action becomes part of an extended and very subtle battlefield. How we choose to speak or to conduct business, where we choose to live, the way we spend our free time, what we teach our children, the food we eat, the books we read, whether we write a thank you note – everything great and small is an opportunity either for the strengthening of Southern culture or for its further decay.

This is the heavy burden of any real folk: the struggle to retain what was handed down to us by our fathers and mothers, sometimes in the face of seemingly overwhelming circumstances.

Nevertheless, we must fight. If we do not, we are guilty of desecrating the memory and achievements of our forebears. We are guilty of condemning Southern children to a rootless existence in the virtual world of Twitter and Snapchat. We are guilty of turning our neighbors, black and white, from fellow Southern kinsmen into ridiculous political caricatures (Republicans, Democrats, etc.) that we then heap hatred upon. We are guilty of turning our villages and towns into the chamberpots of parasitic multinational corporations.

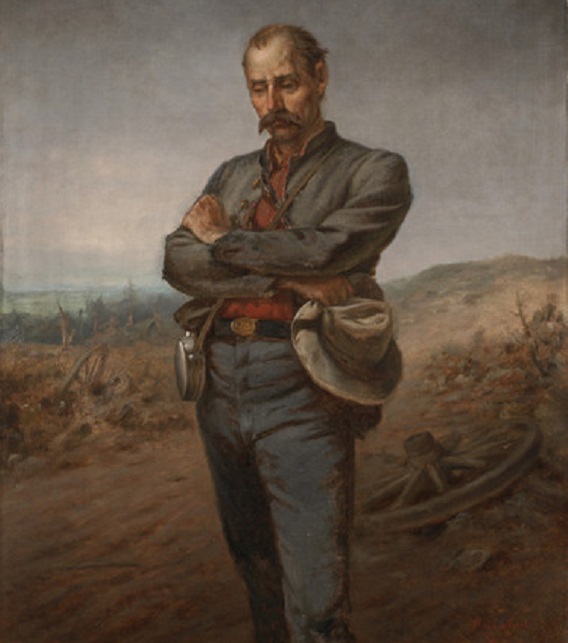

This war may seem unreal, but the scars of its battles are all very real: shuttered churches, rotting barns, insolent youth, disintegrating families and neighborhoods. No Southerner has to look to a movie screen to give his life significance. He is already in the middle of a grave conflict. Every moment is pregnant with meaning. Every action will ripple through time for some future Southern Mladjen to experience in fiery remembrance, just as happened with Allen Tate, which he describes in ‘Ode to the Confederate Dead’:

Turn your eyes to the immoderate past,

Turn to the inscrutable infantry rising

Demons out of the earth they will not last.

Stonewall, Stonewall, and the sunken fields of hemp,

Shiloh, Antietam, Malvern Hill, Bull Run.

Lost in that orient of the thick and fast

You will curse the setting sun.

Cursing only the leaves crying

Like an old man in a storm.

You hear the shout, the crazy hemlocks point

With troubled fingers to the silence which

Smothers you, a mummy, in time.

The hound bitch

Toothless and dying, in a musty cellar

Hears the wind only.

Now that the salt of their blood

Stiffens the saltier oblivion of the sea,

Seals the malignant purity of the flood,

What shall we who count our days and bow

Our heads with a commemorial woe

In the ribboned coats of grim felicity,

What shall we say of the bones, unclean,

Whose verdurous anonymity will grow?

The ragged arms, the ragged heads and eyes

Lost in these acres of the insane green?

The gray lean spiders come, they come and go;

In a tangle of willows without light

The singular screech-owl’s tight

Invisible lyric seeds the mind

With the furious murmur of their chivalry.

Source: https://owlcation.com/humanities/Allen-Tates-Ode-on-the-Confederate-Dead

Few things are of greater weight than the fate of an entire country. No one was or is unimportant in this fight: not the private in the Confederate Army of yesterday, neither the poor farmer nor the blue-collar mechanic of today. Every moment skirmishes are being fought all across Dixie by high-born and low-born alike in the hundreds of decisions all are making (whether they know it or not). The great struggle in all of them is to live deliberately as Southerners. If we are mindful of this and struggle manfully, the South may yet see good days. If we are not mindful of this and live care-free, the dominant, vacuous, materialistic culture manufactured in the bowels of a corporate marketing department will eradicate what is left of Southern folkways.

For the Christian, the battle for his soul ends only at his death. Likewise, the soul of a country lives on until all the sons and daughters who are faithful to her disappear. As long as even so much as a handful of faithful Southerners live, Dixie lives.

Time and God’s Providence working within it are mysterious. So too the connections amongst the folk of a nation: past, present, and future. Even the smallest act of repentance, humility, love, or prayer performed in a remote corner of the land at some forgotten hour may cause some great work to blaze into life that will deeply affect the national life for the better beyond what anyone would have reckoned. We never know where our help will come from.

Let all those therefore who love the South always be diligent in hewing to traditional Southern ways, ‘in season and out of season’ (II Tim. 4:2), putting our hope in God for a good outcome.