In his recent book, Call Sign Chaos : Learning To Lead, former Secretary of Defense James Mattis cited what he termed the current “tribalism” in America as the greatest threat to the nation’s future. Mattis stated in the book that “We are dividing into hostile tribes cheering against each other, fueled by emotion and a mutual disdain that jeopardizes our future, instead of rediscovering our common ground and finding solutions.” These very same words could have easily been used to describe the state of the union a hundred and sixty years ago. In that period, America was also riven by ever-deepening cultural, economic, political, racial and regional divisions which ultimately led to war when one of the “tribes” finally decided that secession was the only solution to resolve such divisions. As in the current state of affairs, the line that divided the various factions in the nation during the mid-Nineteenth Century was not merely the Mason-Dixon Line, as the various multifaceted divisions cut deeply into not only regions and communities all across the country but even separated families in both the North and the South.

While the most visible manifestations of such ambivalence were to be found in the border States of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland and Missouri, such divisions also appeared to a lesser extent in the next tier of States, Illinois, Indiana, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Ohio . . . and even beyond in varying degrees. Due to this crossing of geographic and societal lines, many have termed the War Between the States to be a conflict of brother against brother. One of the most literal examples of this is an incident that appeared in a number of late Nineteenth Century history books, such as Mara Louise Pratt’s 1891 “American History Stories.” This account involved two Kentucky brothers at the Battle of Shiloh in April of 1862 which originated from a notation in the wartime diary of Captain William Moore of Black River, Wisconsin, who raised and led Company “G” of the Tenth Wisconsin Volunteer infantry Regiment. As the regiment did not participate in the Tennessee battle and Moore was killed in a skirmish at Larkinsville, Alabama, only three months after Shiloh, it is not clear how or why the following story appeared in his diary. At any rate, Captain Moore wrote, ”A Kentuckyan in the Federal army was concealed behind a tree, picking off those of the Confederates who might be unfortunate enough to come in range of his ‘old Kentucky Rifle,’ when he discovered a man a short distance from him, in the act of firing at him. He instantly fired on his adversary, and brought him down, badly wounded. In the mean time [sic] the wounded man recognised in the person of his adversary, his own blood Brother, and seeing him draw his gun up to shoot again, called to him by name and begged him for Gods sake not to shoot in that direction again “for that’s Father.” While no specific units were mentioned in Moore’s account, there were four Kentucky infantry regiments, two artillery batteries and a cavalry squadron in General Johnston’s attacking Confederate forces, as well as two Union regiments from Kentucky in General Grant’s Army of the Tennessee that was being assailed at Pittsburg Landing.

Two other brothers from Kentucky, both generals, also fought on opposite sides during the War Between the States, but only one of them, Union Major General Thomas Leonidas Crittenden, fought at Shiloh. His older brother, George Bibb Crittenden, a West Point graduate, chose to resign his commission in the Union Army and join the Confederacy as a colonel and ultimately also rose to the rank of major general. The most controversial division of loyalties in Kentucky, however, was the one that divided President Lincoln’s own family, as the First Lady’s family, the Todds, were slaveholders in Kentucky and several of her close relatives served in the Confederate Army. Her brother, Dr. George Todd, was an Army surgeon who was known more for his cruelty to wounded Union prisoners than for his medical skills. Mary Lincoln’s brother-in-law was Brigadier General Benjamin Helm who served with Kentucky’s famed “Orphan Brigade” at the Battle of Shiloh and was later killed while commanding the brigade at Chickamauga in Georgia. One of her half-brothers, Samuel Todd, was killed at Shiloh while serving in the Twenty-Fourth Louisiana Regiment, while another half-brother, Alexander Todd, acted as aide-de-camp to General Helm at the battle. A third half-brother, David Todd, was also at Shiloh as an officer in the Twenty-First Louisiana Regiment and later was put in charge of Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, but was dismissed by President Davis for his extreme cruelty to Union prisoners.

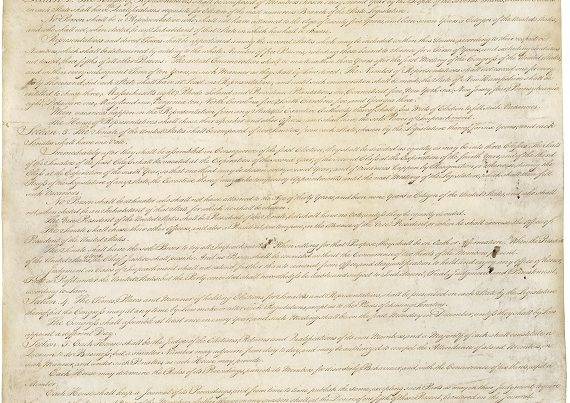

The divisions in loyalties among all those in the military, however, pertained to many other areas and involved a number of individuals in the highest ranks, with over twenty percent of the more than four hundred general officers in the Confederate ranks coming from outside the Confederacy. While seventy of these generals hailed from the four severely divided border States of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland and Missouri, many others were from either an area further north or some foreign country. Of these, the greatest number were the seven each who came from New York State and Pennsylvania, including the highest ranking officer in the Confederate Army, General Samuel Cooper of Dutchess County, New York, who, as Adjutant and Inspector General, was in actual command of all the Confederate Armies. In this group was also another important figure in the Southern war effort, Brigadier General Josiah Gorgas of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who, as Chief of Ordinance for the Confederacy, not only created an entirely new arms and munitions industry in the South but was able to secure a continuous supply of war matériel from Europe. There were also five Confederate generals from Massachusetts, three from New Jersey, two from Maine and one each from Connecticut, Indiana, Iowa and Rhode Island. Moreover, many thousands of individuals from virtually every State and Territory in the Union elected to fight in the ranks of the Confederacy, including so many volunteers from the tribes in the Indian Territory, which is now the State of Oklahoma, that the area was considered a de facto part of the Confederacy. Among these was a Cherokee chief, Stand Watie, who rose to the rank of brigadier general snd became the first and only Native-American to serve as a commanding general in the War. On the Union side there was, of course, Brigadier General Ely Parker, a Seneca from the Tonawanda Reservation in New York who served as General Grant’s adjutant and secretary, but he did not receive his brevetted promotion until April 9, 1865, the day General Lee signed the surrender document at Appomattox that Parker had prepared.

Even the southern counties of President Lincoln’s home State of Illinois, the area known as “Egypt’” was a hotbed of pro-Southern sentiment, with a large group from Jackson and Williamson Counties traveling to Tennessee to join other Confederate sympathizers from Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri and Pennsylvania as part of the Fifteenth Tennessee Volunteer Infantry Regiment, a unit that was involved in heavy fighting at both Shiloh and Chickamauga. As in the four border States, after the start of the War Between the States several of the counties in “Egypt” passed resolutions to secede from the Union, with actual Ordinances of Secession being drawn up. These moves, as was the case in the other areas, were thwarted by the swift intervention of Union troops. In Illinois such units were under the command of Brigadier General Benjamin M. Prentiss who had been sent to Cairo, Illinois, to blockade the Mississippi River and help keep neighboring Kentucky in the Union. There was, however, one small Northern community, Town Line, New York, that actually managed to secede from the Union and did not formally rejoin the United States until after World War Two.

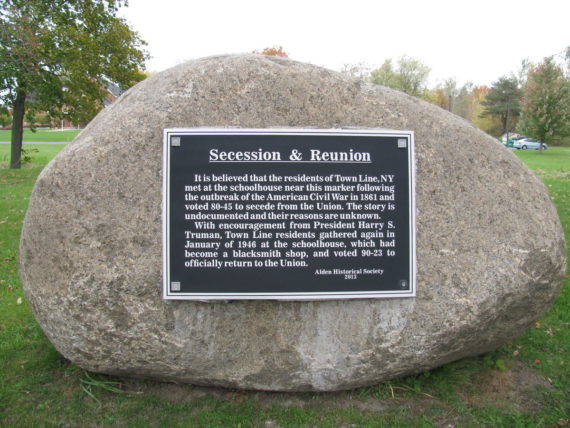

Town Line was then, and still is, an unincorporated hamlet in Erie County, the most western part of New York State that borders on both Canada and Lake Erie. The community was founded mainly by German immigrant farmers who arrived there in the early 1800s and gave the hamlet its name merely because it was situated between the Towns of Alden and Lancaster. The area was famous as a center for the revivalist religious movements during the first half of the Nineteenth Century that were known as the Second Great Awakening. These movements included Mormonism which was founded by Joseph Smith in 1830 only eighty-five miles to the east in Palmyra, and Millerism that was started three years later by William Miller in Washington County on the the eastern border of New York, which in 1863 became known as Seventh-Day Adventism. As far it is known, no one in the area ever owned a slave or had any direct connection with the South. In fact, some in Town Line, such as Mary Cecelia Willis whose home was a “station” on the Underground Railroad that aided runaway slaves, were active abolitionists with close ties to Frederick Douglass who published the anti-slavery newspaper “North Star” in the nearby city of Rochester. The local residents had also voted overwhelming for Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 elections. Despite all this, sometime after the start of the War Between the States in 1861, a hundred twenty-five of the hamlet’s few hundred residents gathered at the local schoolhouse and by a vote of eighty-five to forty, elected to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy. As no formal notice of secession was ever given to the United States, nor any application for admission ever sent to the Confederate States, no action was ever taken in Washington nor any recognition ever given from Richmond.

No public record of the vote to secede from the Union has ever been found, and virtually all that is known about the action is from oral history that has been handed down from one generation to the next. Some historians have stated that the move was taken to avoid Lincoln’s call for seventy-five thousand troops which it was felt would have stripped the hamlet of most of its able-bodied men. This, however, flies in the face of the fact that at least five local residents went South to fight for the Confederacy, while more than twenty others volunteered for military service with the Union. The only written document that was ever discovered was a letter by a resident who was twelve years old when the 1861 vote was held which indicated that the action was taken over the question of slavery but this too seems unlikely, as virtually all the local residents were openly opposed to slavery. Nevertheless, the connection with the Confederacy was continued all through the War, and several of Town Line’s residents who were accused of being “Copperheads” had to flee to Canada. After the War, a Confederate flag continued to be raised daily in the hamlet, Confederate uniforms were predominantly worn during reenactments and both “Dixie” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” were played at all local events. Even as late as 2011, the members of the Town Line fire department wore patches bearing crossed American and Confederate flags and the motto “Last of the Rebels” and a local hardware store to this day displays a sign reading “The Last Rebel Business Still Taking a Stand.”

In 1945, a Buffalo newspaper carried a human-interest article on Town Line’s secession and thirty of the hamlet’s resident held a straw vote on returning to the United States . . . with only one resident voting in favor of reunion. The vote forced some heated arguments on the long-dormant matter and later that year, after many local World War Two veterans returned home, it was decided that the issue should be discussed more seriously and a letter was sent to President Truman asking for his advice. Truman suggested that another vote be held after everyone enjoyed a community barbecue. Somehow news of the controversy and the letter to the president reached Hollywood and Twentieth Century Fox, which had just produced the film “Colonel Effingham’s Raid,” the story of a retired Army officer who returned to his hometown in Georgia and started a movement to save a local Confederate monument, decided to get into the act. While the actual 1946 premiere was to be held on January 24th in Atlanta, Georgia, the studio offered to hold a dual showing of the film in Town Line. As there was no theater in the hamlet, the movie was to be shown at the firehouse. The community declared January 24th a local holiday, held the suggested barbecue at the building where the 1861 secession vote had been taken, named the main intersection “Truman Square” and paraded to the firehouse to view the movie. Following that, a new ballot on rejoining the United States was taken by a hundred thirteen residents and this time it was passed by a vote of ninety to twenty-three. After the vote was announced, the Confederate flag that had flown over the hamlet for more than eight decades was lowered and the Stars and Stripes raised in its place, the band first played “Dixie” and then “The Star-Spangled Banner” and the voters all took the same official Oath of Allegiance that had been taken by Confederates after their surrender in 1865. Thus, the War Between the States and the action that went unnoticed by both the Confederacy and the Union for over eighty years was finally laid to rest for the only area in the North that actually managed to secede from the United States without suffering the intervention or invasion of a single Federal soldier.