The news media rarely, if ever, focuses on the impact on society and culture the price of economic growth. Nor do politicians. This begs the question, what price is extracted from society and culture in the pursuit of economic growth, in particular, when the central and state governments along with the central bank play key roles, namely in the of the growth of debt as an asset and not a liability, state regulation, tax revenue increases and regulatory capture by industry. The pursuit of prosperity has a dramatic impact on the demographic makeup of the South, our value system and ultimately the culture of the southern nation.

The period of Reconstruction set forth movement toward a new period of development as the South sought new methods to spur economic growth in an effort to recover from economic devastation resulting from the war. As industrialization marched slowly across the Republic, mill towns sprang up across the South. The College of William and Mary Center for Agricultural Research describes this as the result of the erosion of “agricultural self-sufficiency” that “trapped yeomen farmers in a cycle of debt”. This, in turn, led to the availability of a workforce of otherwise poor Southerners to take up factory jobs in exchange for the benefit of a regular wage. Northern industrialists would utilize the economic devastation of the South to their advantage.

This system of mill towns that sprang up across the South would be maintained well into the 20th century, as towns and cities such as Atlanta and Charlotte would come to view added economic growth as a means to modernize and grow their economies, resulting in increased tax revenues. Additionally, it was not unusual for municipal and state leaders to view their citizens with embarrassment, pointing to their “economic and cultural backwardness” leading them to encourage economic growth and migration as a means to alter demographics and propel their economies into a position to challenge older industrial centers within the United States–generally in the North. It was at this point that governments made the decision either implicitly or indirectly that culture was either of no consequence or that it needed to be destroyed. This can be said to be the rise of what many refer to as the ‘New South’.

The result of the economic growth of the South, particularly in states such as North and South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Florida, Texas and Virginia has resulted in an explosion of population growth. According to the Harvard University Taubman Center for State and Local Government, the South’s “share of the national population has increased from 24 percent to 30 percent since 1950. From 1950 to 2000, the average income in the South increased from 76 percent of the national average to 94 percent of the national average, while housing prices rose from 83 percent to 91 percent of the national average.” An economic success story by any conventional means, and one that conveyed a reversal of economic malaise commonly associated with the region since the War for Southern Independence. Few, if any, policy analysts, much less elected leaders have spoken about what price this economic growth has extracted on the native population in terms of social, cultural and political power.

Culture, according to the Cambridge University dictionary is, ‘the way of life of a particular people, especially as shown in their ordinary behavior and habits, their attitudes toward each other, and their moral and religious beliefs’. Culture is also not static, it is ever-changing but each movement in evolution in culture is directly related to what came before. It must be noted that what we refer to as Southern culture is a grouping of smaller cultures into one larger regional grouping; and these cultures developed throughout hundreds of years and are derivative of their British, Western European and African parent civilizations. Our Southern culture includes, but is by no means limited to, the Calvinistic Christianity of the Southern backcountry, the food, music, and the social bonds that link people and communities to one another. These are but a sample of some of the things that enabled people to take up arms, defend one another and even face the threat of death during the times of economic crisis, famine or war. What then happens to the South and Southern culture when governments prioritize economic development and population growth?

Data from CityLab show population growth in nearly all urban areas in the South over the past 10 years, while rural areas continue to demonstrate population decline correlated with job losses and business closures. Simply put, people are moving to where economic opportunity is available. This is not simply a regional migration as the Northeast and Rust Belt states have lost population and migration continues unabated to Sun Belt cities. The politics of the South have continued to shift along with this migration, as cities once considered to lean conservative or at least moderate have shifted, not only within the cities but also in the suburbs, to an affinity for left-leaning political candidates. Tax revenues, unsurprisingly, have also continued to climb in these areas as migration and commercial and housing construction starts have skyrocketed. Migration has also lead to the election of an increasing number of municipal and state leaders who have no native links to the areas in which they represent. In short, this has resulted in the replacement of the native population (and culture) within these areas of economic growth.

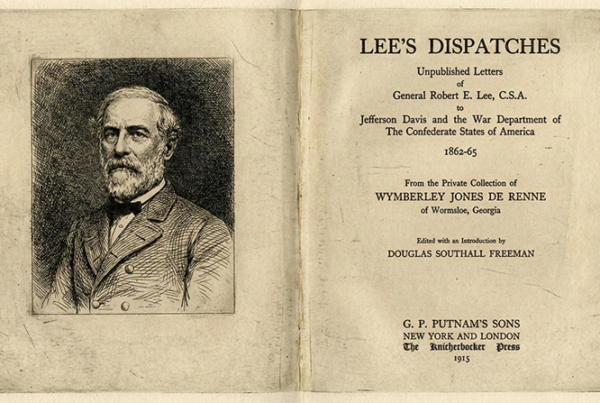

Cultural replacement in these areas has taken the focus off of heritage celebrations, monuments, vernacular architecture, historic preservation efforts, and in fact, turned the tables back on the native culture and history of the area. Atlanta has placed a number of “contextual” signage on Confederate monuments, the Museum of the Confederacy has shut in Richmond, a war monument was removed in Winston-Salem (led no less by municipal leadership where the vast majority are not from North Carolina), and gun rights are restricted in areas where high levels of migration from the North and Midwest have overwhelmed the native population. Left-leaning candidates have won office in Virginia, North Carolina and nearly won the governorship in the state of Georgia in 2018. All of this without regard for the people who created and gave life to these cities, towns, and regions.

The rural South, on the other hand, can be said to have been able to hold onto more of its cultural norms, traditions, and heritage. However, the focus on increasing tax revenues at the expense of people has resulted in declining populations in many of the small towns and communities within the South. A recent article from the Pew Charitable Trusts on the loss of rural grocery stores outlines one of the many difficulties that these areas have in retaining their native sons and daughters. It is not uncommon for small communities to look to an outside ‘savior’ such as a manufacturing facility or chemical plant for economic rejuvenation. Unfortunately, such efforts may be a folly in the long term. Outside organizations will only utilize these areas for a low paid workforce; lax state environmental regulations and tax benefits and will likely stay as long as it is economically beneficial. This creates a “race to the bottom” in the competition between areas in economic decline. Small town Southerners, particularly young people, will likely wish to relocate to the aforementioned urban areas, where their culture and social norms will be subsumed into the progressive, materialistic (and postmaterialistic) norms that now dominate many cities in the United States. Thus, the result is that the regional distinctiveness of the South is further weakened.

The South from its genesis was an agrarian society, and this is irrevocably linked to the cultural customs of stewardship of the land, faith, kinship and honor that defined our region from the 17th century through the mid-19th century. Despite political economist and philosopher, John Stuart Mill who in 1848, stated that cultural norms function to limit an individual’s pursuit of their self-interests, it has become the norm that society now functions to encourage self-interest, particularly where that self-interest results in economic activity. The resulting casualty is our heritage and cultural distinctiveness.

However, there are a few bright spots in this otherwise grim summary of our current situation. States such as North Carolina have enacted programs to attempt to spur on economic development for entrepreneurs in rural areas. However, the problem persists that states are being overwhelmed through an influx of migration from the north, and an emphasis on material wealth over kith and kin. Until there is a reset in our economy and society the diagnosis is rather dire. Southerners must take active steps within their local communities to support local businesses, teach their children to take an active interest in their heritage and elect officials who will not sell out the past and future generations for the benefit of the present.