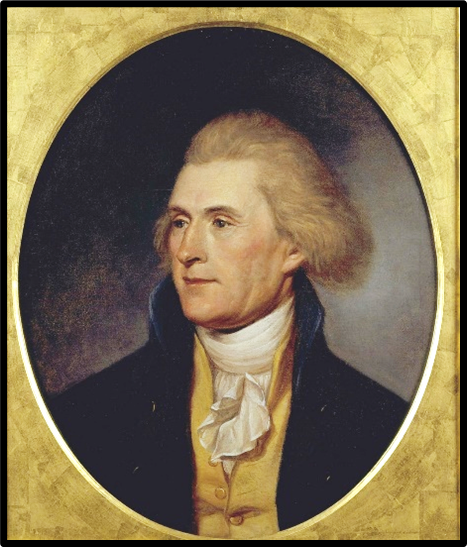

On June 9, 1776, the Continental Congress appointed a committee of five men—Virginian Thomas Jefferson, New Englander John Adams, Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin, New Yorker Robert Livingston, and New Englander Roger Sherman—to draft a declaration of American independence. The motivation for the document—the one given to the committee by the Congress—is certainly conveyed in the opening salvo of Jefferson’s draft: to declare openly and unabashedly to the world at large the reasons for Colonists’ revolution against their mother-country.

The options, of course, were for the committee as a whole to draft the document or for one member or two members to do so. The former was certainly adjudged to be slow and inefficient. So, Jefferson, fresh from the celebrity awarded him with his Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774), was saddled with the task.

The task of the first draft was thought best to be done by a Virginian, as Virginia was the largest state and the resolution was made by Richard Henry Lee, a Virginian, on June 7, 1776, and seconded by Adams. The task—deemed redundant by Lee, Adams, and George Wythe, as and the proclamation would merely make de jure a scenario de facto (American independence)—eventually fell upon Jefferson. In his journal, Adams writes of a sentiment he expressed to Jefferson concerning why Jefferson, not he, should be the drafter: “Reason first, you are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second, I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third, you can write ten times better than I can.” Adams’ account, often cited in biographies and documentaries, Jefferson contradicts in a late letter to James Madison (30 Aug. 1823). “Mr. Adams[’] memory has led him into unquestionable error. … The committee of 5 met, no such thing as a sub-committee was proposed, but they unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught.”

And so, Jefferson retired to the second floor of a three-story brick house—the newly constructed (1775) Graff House—at Seventh and Market Streets in Philadelphia, where he worked on the project from June 11 to June 28. Jefferson brought with him a recently made portable mahogany writing-box, which cabinet-maker Benjamin Randolph, Jefferson’s former landlord while in Philadelphia in 1775, had made for Jefferson from Jefferson’s sketch. The rectangular box consisted of an adjustable top for reading or writing and a drawer for paper, pens, and ink. The table Jefferson would use throughout his life until he would gift the box to the husband of granddaughter Ellen Randolph Coolidge as a wedding present. Jefferson writes (14 Nov. 1825): “It claims no merit of particular beauty. It is plain, neat, convenient, and, taking no more room on the writing table than a moderate quarto volume, it yet displays itself sufficiently for any writing.” He adds: “Mr. Coolidge must do me the favor of accepting this. Its imaginary value will increase with years, and if he lives to my age, or another half-century, he may see it carried in the procession of our nation’s birthday, as the relics of the Saints are in those of the Church.” The writing-box, as Figure 1 indicates, shows that Jefferson put considerable thought into construction of the table.

Retiring to a secluded spot was not uncommon behavior for Jefferson. He was ever comfortable in retreat, in the solitude of study, and he needed some amount of retreat each day. Solitude was a necessity when he faced an arduous task, requiring research and focus. While in France, for instance, he sometimes retired to a monastery at Mont Calvaire, to the west of the bustle of Paris, to attend to work, when it piled up. In Virginia, his residence at Poplar Forest, some 70 miles southwest of Monticello, was his late-in-life getaway “monastery”—his place for leisure, reflection, and study.

Of the newly constructed Graff House of Philadelphia, Jefferson merely writes in his memorandum book of 1776, “Took lodgings at Graaf’s.” Jacob and Maria Graff were members of Philadelphia’s large German community. Jacob learned contracting from his father, a bricklayer and businessman, and joined his father in business, which entailed inter alia the rental and sale of properties.

Some 50 years later in a letter to James Mease (16 Sept. 1825), Jefferson later suffers to recall what he can of the residence.

Jefferson writes first of what he can confirm from written documents. “at the time of writing that instrument I lodged in the house of a mr Graaf, a new brick house 3. stories high of which I rented the 2d floor consisting of a parlour and bed room ready furnished. in that parlour I wrote habitually and in it wrote this paper [the Declaration] particularly.”

Jefferson then adds what he can recall from “a memory too much decayed to be relied on with much confidence.” Jacob Graff was young, German, and newly married. “I think he was a bricklayer, and that his house was on the S. side of Market [now High] street, probably between 7th & 8th or perhaps higher and if not then the only house on that part of the street.” He recalls only that it was a corner house. The house was demolished in 1883, but it was reconstructed, from old photos, in 1775 in readiness for the 200th anniversary of the United States. The drawing in Figure 2 shows a gabled roof; that of Figure 3, a hipped roof. The oldest photos show the house, doubled in size—with four front windows on each floor and a hipped roof.

The letter is composed in reply to a missive from Dr. James Mease (1771–1846, 8 Sept. 1825)—horticulturalist, medical doctor, Philadelphian, and inventor of tomato-based catsup—in which Mease asks about the building in which Jefferson wrote his Declaration:

As I view every circumstance connected with the glorious instrument composed by you, which told the world we were determined to be free, as highly interesting and important, I take the liberty to ask of you, in which house, and in which room of the house, you composed it. If a private house, the name of the person who kept it at the time, would be Acceptable. If “the patriotism” of a Common traveller “would gain force upon the plain of Marathon,” that of a native American, the son of a man who fought for the glorious prize his children, & our Country enjoy, would recieve additional excitement by the Knowledge of the fact I sollicit. when with a few of the Descendants of the soldiers of 1776, he will hereafter celebrate the anniversary of our National birth day in the Room, whence the eloquent defence of the measure taken by our rulers, and appeal to the world, issued.—It is also my intention, if enabled to do so, to Record the fact on the Minutes of the historical Committee of the Amer: Philos: Society—

Removal to the Graff House was not just for the sake of having a quiet space for conduction of business. Jefferson expiscates in a letter to Thomas Nelson (16 May 1776). “I am at present in our old lodgings tho’ I think, as the excessive heats of the city are coming on fast, to endeavor to get lodgings in the skirts of the town where I may have the benefit of a freely circulating air.” The “old lodgings” of which Jefferson writes was the house of Benjamin Randolph, cabinetmaker, on Chestnut Street between Third and Fourth Streets. Jefferson notes in his memorandum book that he arrived in Philadelphia on April 14, 1776. He notes on May 27 that he has paid Randolph “for 8. Days lodging 40/.” Beginning on May 20, 1775, he had stayed with Randolph on several occasions in 1775, when in Philadelphia. There are references to paid rent on June 8, July 29, Oct. 16, Nov. 25, and Dec. 27.

Jefferson took with him his trusted valet, Robert “Bob” Hemings. They would stay in the Graff House only till September 3, 1776, when he left Philadelphia for Monticello to be with his wife, who was ill and to begin work on Virginian business. Jefferson and Hemings arrived on September 9. Jefferson then turned to the arduous task of revisal of the laws of Virginia.

When finished with his initial draft of the Declaration, Jefferson handed a copy, his fair copy, to Franklin and Adams for their corrections. The two made merely “verbal” alterations and the Continental Congress received the fair copy on June 28 and made substantial edits, thereby reducing the document by some one-quarter in length.

In prior publications, my focus has been Jefferson’s fair copy, for the document that comes down to us today as Jefferson’s Declaration was heavily redacted. Because of those redactions, many scholars are wont to assert that Jefferson was merely one of many authors of the document—that Benjamin Franklin and John Adams of the committee suggested minor edits and the Continental Congress substantially blue-penciled Jefferson’s fair copy. That noted, the basic structure, narrative, and argumentative thread of the document have not been changed by the substantive edits, so I examine the finished document and rightfully treat it as Jefferson’s.

For ease of understanding, the Declaration can be readily broken into four main parts.

First, there’s the opening salvo in the first paragraph, comprising one sentence, which explains the purpose of writing the document:

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

The 71-word sentence, parturient, states that when there is need of a political break between two peoples, historically considered as one, for the sake of those breaking to assume a “separate and equal station,” the people that are separating ought to give their reasons for separation. Moreover, such reasons must be put before the tribunal of all of mankind. Again, Jefferson also states, with justification yet to come, that such a break has the sanction of the laws of nature and of God. This is a very democratic opening to a very democratic document. A people wishing to break from a polity historically merely do so. There is not written justification for that break.

Second, there is Jefferson’s argument in justification of the American Revolution.

Jefferson begins with certain “self-evident” truths:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

The statements are two: (1) All men are from creation equal and (2) the Creator has given each certain unalienable rights or “liberties” (life, liberty, and pursuit of Happiness).

In his fair copy, Jefferson’s text is subtly, but substantively different:

We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness.

Here Jefferson writes that all men are created “equal & independent”; that “from that equal creation,” all have the rights “to the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness.”

The difference is weighty. In the finished document, there is listed, without expiscation, merely two self-evident truths. Being self-evident, there is no need of justifying either. In the fair copy, Jefferson mentions that men are born not merely equal, but also equal and independent. Furthermore, in the fair copy, Jefferson is clear that the “liberties” humans deserve are derivatives of their “equal creation.” Thus, it is on account of human equality that we deserve liberties. In sum, humans are axially equal creatures and only secondarily or derivatively free creatures.

Next, there is the statement concerning the proper end of government, which is the same in both documents:

To secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Here one might ask this: If humans are equal and given, at birth, unalienable rights, why then do they need governments to secure their rights?

Rousseau maintains Locke

Given that “aristocrats” for centuries have enjoyed themselves by burking humans by denying human rights, Jefferson, then, turns to the justification of the Colonists’ revolution, or of any revolution on behalf of human rights:

Whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

The sentiment is in gist equivalent to his Fair Copy.

Next, Jefferson adds some qualifying remarks—the same in the Fair copy and finished product:

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

The sentiment here is, by appeal to experience, that governments ought not to be changed without proper warrant. Even in the best-intending governments, there are abuses of rights, correctable over time. Such abuses, temporary inconveniences, are and ought to be sufferable. Were people to meet every governmental abuse of rights with revolution, there would be perpetual bedlam. Yet there are instances in which people continually suffer from abuses of rights such that the governmental intendment is shown to be despotism, then the people are justified, and right, to rise up and remove the despots from power.

That is just what has been increasingly happening in Colonial America:

Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

Third, there’s a lengthy list of some 24 or more grievances—“Facts … submitted to a candid world”—which aim to show King George III’s behavior to be arbitrary and tyrannical. Some examples are that he has refused to sanction wholesome public laws, he repeated dissolves “Representative Houses” to crush opposition, he has appointed judges to represent his will, he has implemented taxation without consent, and he has kept standing armies in times of peace. These offer evidence of Jefferson’s tendency to exhaustion. He was not content to offer reasons sufficient to show George III’s misconduct. He wished to marshal every shred of evidence, to turn up every stone as it were, for misconduct.

Finally, there’s the concluding paragraph which sums the eloquently written document:

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Thus, the Declaration is a lengthy argument—given in gist mostly in the second paragraph.

1) All people are created by God as equals.

2) All people are endowed with certain rights (life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness)

3) Humans are naturally gregarious—they tend to gather in large societies.

4) Large societies lead to abuses of rights and disregard of human equality.

5) So, governments are needed to oversee the relations among humans (4).

6) Governmental power is derived from the consent of the people (1–5).

7) So, the main task of a government is to secure its citizens’ rights (6).

8) Governors often rule not as God and nature dictate, but according to self-interest.

9) So, there needs to be people-imposed checks on governmental actions (7–8).

10) When any government fails to secure its citizens’ rights, the citizens have a right to abolish it and institute a new government (7–9).

11) King George III has abusively violated the British colonists’ rights (18 grievances).

12) So, the colonists have a right to form their own government in keeping with their own notions of their safety and happiness.

Enjoy the video and share comments….

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily the views of the Abbeville Institute.

Thank you. The brilliance of the document humbles me. Thanks for the exposition.

You are welcome!