States’ rights are anathema to the historical profession, viewed as nothing more than a specious pretext for chattel slavery. A prominent, Pulitzer-winning court historian of the “Camelot” Administration dubbed states’ rights a “fetish.” Another Pulitizer-winning scholar of what he outrageously terms the “War of Southern Aggression” claims that to Southerners, “liberty” was just a code word for “slavery.” A past president of the St. George Tucker Society declared states’ rights to be “simply a philosophical justification for the more fundamental institutions of slavery and segregation” (ironically, Tucker, his society’s namesake, was the Virginia jurist who systematized the doctrine of states’ rights while forcefully arguing for emancipation generations before the emergence of Northern abolitionism). Naturally, postbellum apologias by former Confederates are denounced as deceitful attempts to rewrite history in accord with pathetic “myths” developed to cope with the shame of defeat and guilt of slavery. Instead of acknowledging that these testimonies are a valid part of the historical record and could provide clarity and context to the causes, conduct, and consequences of the so-called “Civil War,” the victors have silenced the voices of the vanquished and proclaimed states’ rights discredited.

All of these sneering pronouncements, however, fly in the face of the facts. Far from a cheap creed concocted to keep blacks in bondage, states’ rights were a preeminent pillar of Southern political philosophy, stemming from sincere beliefs about the republican nature of the Union and a deep passion for self-government. As a reader wrote to the Richmond Examiner on August 2nd, 1864:

Our enemies have diligently labored to make all mankind believe that the people of these States have set up a pretended State sovereignty, and based themselves upon that ostensibly, while their real object has been only to preserve to themselves the property in so many negroes, worth so many millions of dollars. The direct reverse is the truth. The question of slavery is only one of the minor issues; and the cause of the war, the whole cause, on our part, is the maintenance of the sovereign independence of these States.

The principle of states’ rights was at the heart of many controversial issues between the North and the South, such as war, territorial expansion, tariffs, internal improvements, and national banking. To a significant extent, the division over states’ rights was the predominant force in Antebellum America. “Of all the problems which beset the United States of America during the century from the Declaration of Independence to the end of Reconstruction,” concludes Forrest McDonald, renowned scholar of early American history, “the most pervasive concerned disagreements about the nature of the Union and the line to be drawn between the authority of the general government and that of the several states.” According to Joseph R. Stromberg, the republican tradition of states’ rights was “the inheritance the South received from its Revolutionary forefathers and…the South had remained truer to the original understanding of it than had the North.” Indeed, from the foundation of the Union to its dissolution, distinguished Southern leaders penned magnificent political treatises which exhaustively established the constitutional origin of states’ rights and expounded upon their virtues in protecting minorities from majoritarian tyranny. Thomas Jefferson himself considered states’ rights the “foundation” of the Constitution, “the true barriers of our liberty,” and “the surest bulwarks against anti-republican tendencies.” The aim of this essay series is to restore the greatest of these neglected works to their rightful glory as a legitimate Southern political philosophy.

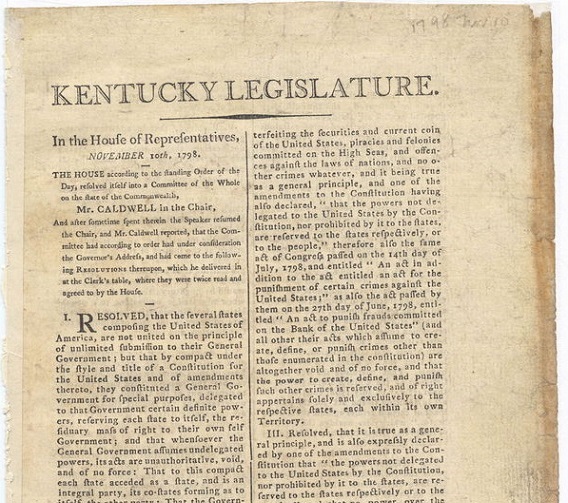

In the fall of 1798, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson (currently serving as Vice President beneath John Adams) secretly wrote the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions in protest against the Alien and Sedition Acts. These so-called laws, enacted to suppress dissent against the unpopular Federalist Party, gave the president unilateral power to imprison or deport immigrants deemed a threat to national security and criminalized criticism of the federal government. At the time, severe political opposition to the Federalists was sweeping the young republic, and many public figures, particularly members of the press, were fined and imprisoned under the Sedition Act for condemning the corruption and taxes of the Adams Administration. “It is true that we are completely under the saddle of Massachusetts and Connecticut,” Jefferson wrote in 1796 of secession stirrings in Virginia and North Carolina, “and that they ride us very hard, cruelly insulting our feelings and exhausting our strength and substance.” Even as early as the late 18th century, fault lines were forming along the Mason-Dixon. While Madison wrote on behalf of Virginia, the bastion of republicanism, Jefferson wrote on behalf of Kentucky, an independent-spirited frontier state from the bosom of the Old Dominion herself.

“Resolved, that the several States comprising the United States of America are not united on the principle of unlimited submission to their general government,” Jefferson began with a bang. When the states ratified the Constitution, they “constituted a general government for special purposes,” and “delegated to that government certain definite powers, reserving, each State to itself, the residuary mass of right to their own self-government.” Jefferson cited the Tenth Amendment as express affirmation of the “general principle” that the states retained any powers which they did not delegate to the federal government. If the federal government ever usurped power from the states, then its acts of usurpation were as illegitimate as they were tyrannous. “Whensoever the general government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force.” An unconstitutional law was no true law at all.

Jefferson denied that the federal government was solely entrusted with interpreting the Constitution and limiting its own authority. “The government created by this compact was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself,” for, “that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers.” The states, however, as the sovereign parties to the Constitution, not only had the right to determine the constitutionality of federal legislation, but also to resist whatever legislation they deemed unconstitutional. “As in all other cases of compact among powers having no common judge, each party has an equal right to judge for itself, as well of infractions as of mode and measure of redress.”

After establishing the rights of the states in the constitutional compact, Jefferson applied these principles to the issue at hand. Since “no power over the freedom of religion, freedom of speech, or freedom of the press” was delegated to the federal government, any federal legislation restricting those basic freedoms was unconstitutional. In fact, Jefferson noted that the First Amendment specifically protected those basic freedoms from the federal government. “Therefore, [the Sedition Act], which does oblige the freedom of the press, is not law, but is altogether void, and of no force.” Furthermore, since the Constitution did not differentiate between “our alien friends” and “citizens,” the Alien Act, which deprived foreigners of habeas corpus, “is therefore not law, but utterly void and of no force.”

Jefferson warned that construing the general-welfare and necessary-and-proper clause to grant implied powers to the federal government “goes to the destruction of all limits prescribed to their powers by the Constitution.” Those clauses were “meant by the instrument to be subsidiary only to the execution of limited powers,” and “ought not to be so construed as themselves to give unlimited powers, nor a part be so taken as to destroy the whole residue of the instrument.” Jefferson was responding to an expansive interpretation of the Constitution which Federalists had contrived in order to justify the Alien and Sedition Acts, as well as a mercantilist economic program of heavy tariffs, a central bank, and a high national debt.

While Kentucky was loyal to the Union as it was first founded – a federal compact of “peace, happiness, and prosperity of all the States” – it would not “submit to undelegated, and consequently unlimited power in no men, or body of men on earth.” If delegated, lawful powers were abused, then the people would be free to choose new elected officials, but if undelegated powers were usurped, “a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy.” Jefferson viewed nullification as a “natural right,” without which the states would “be under the dominion, absolute and unlimited, of whatsoever might exercise this right of judgment for them.” Since Congress was not a party to the Constitution, but merely a “creature” created by the states, it and its “assumptions of power” were therefore “subject…to the final judgment of those by whom and for whose use itself and its powers were all created.” Jefferson closed the Kentucky Resolutions with a thundering tirade against the tyranny of the Alien and Sedition Acts. These usurpations centralized the roles of “accuser, counsel, judge, and jury” in the president, “whose suspicions may be the evidence, his order the sentence, his officer the executioner, and his breast the sole record.” Jefferson noted the acts turned a large portion of the population into “outlaws,” and feared that anyone who opposed the federal government by daring to “reclaim the constitutional rights and liberties of the States and people” could be seriously punished. The “friendless alien” was merely the “safest subject of a first experiment” which would eventually set a precedent that would eventually extend to all citizens. Indeed, for writing the Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson himself could have been convicted of treason under the Sedition Act. “Unless arrested at the threshold,” these acts of usurpation would “drive these States into revolution and blood,” subverting “republican government” for government “by a rod of iron.” Jefferson concluded, “In questions of power, then, let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.”

Meanwhile, Madison wrote resolutions of his own for Virginia. “Resolved, that the General Government of Virginia doth unequivocally express a firm resolution to maintain and defend the Constitution of the United States, and the Constitution of this state, against every aggression, either foreign or domestic.” Because of Virginia’s “warm attachment to the Union of the States…it is their duty to watch over and oppose any infraction of those principles which constitute the only basis of that Union.” According to Madison, the Constitution was a compact between sovereign states by which they delegated particular powers to the federal government. “This Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact, to which the states are parties.” These powers were “limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting the compact,” and were “no further valid than they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact.” In other words, the legitimate powers of the federal government were limited to those which the states had delegated in the Constitution. If the federal government ever violates the constitutional limits on its power, however, then the states must invoke their sovereignty and unite against encroachment. “In the case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining…the authorities, rights, and liberties pertaining to them.”

Madison lamented “sundry instances” of efforts of the federal government “to enlarge its powers by forced constructions of the constitutional charter which defines them.” Twisting the general-welfare and necessary-and-proper clauses into conferrals of implied powers undermined the Constitution’s enumeration of powers. “Implications have appeared of a design to expand certain general phrases…so as to destroy the meaning and effect, of the particular enumeration which necessarily explains and limits the general phrases.” Unchecked, this interpretation would ultimately “consolidate the states by degrees, into one sovereignty, the obvious tendency of which would be to transform the present republican system of the United States, into an absolute, or at best a mixed monarchy.” Of all these usurpations, however, “The General Assembly doth particularly protest against the palpable and alarming infraction of the Constitution, in the two late cases of the ‘Alien and Sedition Acts,’ which not only consolidated legislative and judicial functions into the executive branch, but also “exercises a power nowhere delegated to the federal government.” Indeed, aggression against freedom of speech and the press “ought to produce universal alarm,” for “the right of freely examining public characters” and “the free communication of the people thereon” was “the only effectual guardian of every other right.” Madison noted that Virginia, as a condition of ratifying the Constitution, had stipulated that “the liberty of Conscience and of the Press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained, or modified by any authority of the United States,” and recommended that the federal government affirm these basic freedoms in what ultimately became the First Amendment. Madison closed by appealing “to the like dispositions of the other states, in confidence that they will concur with this commonwealth in declaring, as it does hereby declare, that the acts aforesaid, are unconstitutional; and that the necessary and proper measures will be taken by each, for cooperating with this state, in maintaining the Authorities, Rights, and Liberties, referred to the States respectively, or to the people.”

Jefferson and Madison did not invent nullification and interposition as provisional defenses of civil liberties, as some have speculated, but derived them from the principles and intentions of those who framed and ratified the Constitution. The differences in style and substance between the revolutionary, idealistic Jefferson and conservative, legalistic Madison are evident. Jefferson’s concept of nullification encouraged states, whether individually or collectively, to resist federal legislation which they, in their sovereign capacity, found unconstitutional. Madison’s prescription of interposition was more moderate, counseling the states to act collectively against unconstitutional federal legislation. Despite these differences, both agreed on the basics: the Constitution was a compact between sovereign states; the rightful powers of the federal government were limited to those that had been delegated by the states; all undelegated powers were reserved unto the states. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were the first systematic statement of states’ rights in American history, and the “compact theory of the Union” which they advanced would influence and inspire Americans – particularly Southerners – for generations. As late as 1860, the Northern and Southern factions of the Democratic Party were pledging allegiance to “The Principles of 1798” as “one of the main foundations of our political creed.”

Thanks to the efforts of John Breckenridge in Kentucky and John Taylor of Caroline in Virginia, the Bluegrass and Old Dominion States both adopted the resolutions. In response to these assertions of states’ rights, Alexander Hamilton, who had once assured Anti-Federalist dissidents that the federal government would never resort to coercion against the states (dismissing it as “one of the maddest projects that was ever devised”), argued for deploying the army he was amassing to “put Virginia to the test of resistance.” In 1799, Jefferson wrote to Madison that unless the federal government recognized “the true principles of our federal compact,” the states should “sever ourselves from that union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self-government which we have reserved, and in which alone we see liberty, safety, and happiness” (in other words, secession!). Although no other state legislature supported the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, the American people did, unseating Adams and the Federalists for Jefferson and his “Democratic-Republicans” in the 1800 elections. While the defeated Federalists, with their narrow agenda and elitist airs, dissolved in disgrace, Jefferson’s grassroots coalition enjoyed a generation of national ascendancy.

Confusing the integrity of the Constitution with the power of the federal government, a bestselling historian claims that Jefferson’s “radical doctrine of states’ rights…effectively undermined the Constitution.” A popular neo-conservative radio host often sputters against modern-day nullifiers as “neo-Confederates,” apparently unaware of the compliment he is paying the rebels in gray by recognizing the distinguished pedigree of their beliefs. In fact, states’ rights, as Jefferson and Madison explained, are an essential part of the system of checks and balances and separation of powers designed to preserve the integrity of the Constitution, the liberties of the people, and the peace of the Union.