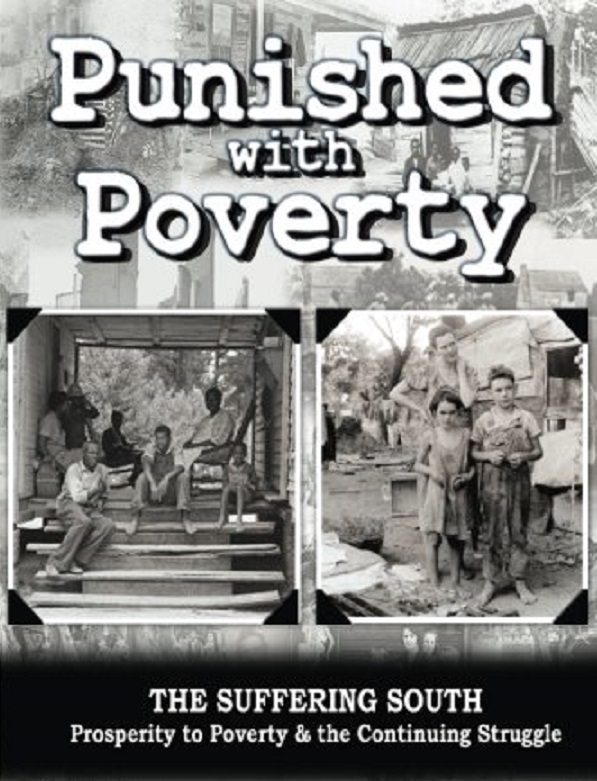

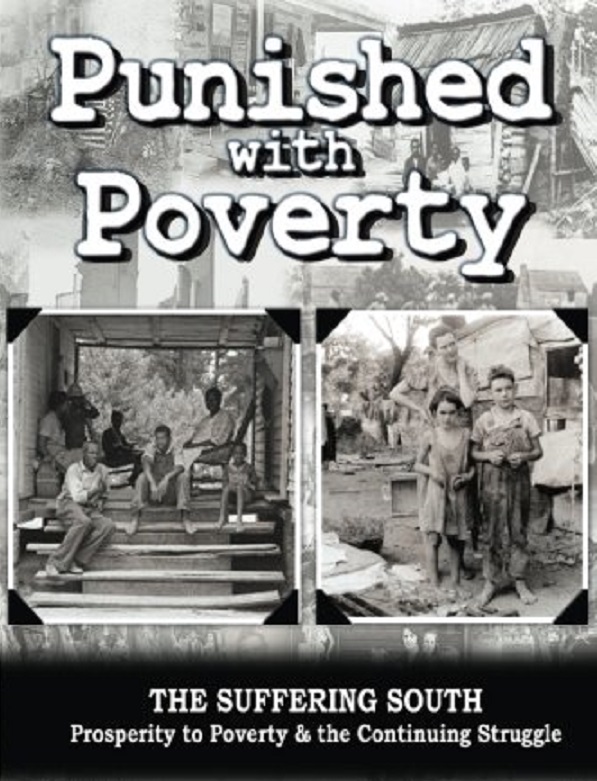

A review of Punished with Poverty: The Suffering South-Prosperity to Poverty & the Continuing Struggle (Shotwell, 2016) by James Ronald and Walter Donald Kennedy

This is one of the most important works of American history that has appeared in many a year. If enough Southern people could absorb the lesson of this book, it would bring about a complete reorientation of American politics.

The Kennedys have long been known as devoted, enterprising, and prolific defenders of the Southern people. In Punished with Poverty they have established, contrary to all official opinion, that the main theme of Southern history since 1865 is not RACE. It is POVERTY–shared by black and white Southerners alike.

The role of the Southern people and region in the American economic empire has been that of a colony to be exploited. From being the most prosperous part of the American empire in 1860,we have become, unto this very day, the most poverty-stricken, a source of cheap labour and raw materials for Northern capital. Though in recent decades our prosperity has grown some, we remain relatively the poorest people of the country.

It is important to note that the South was the more wealthy region in 1860, economically comfortable for all. This was not because of a few wealthy planters, who were only prominent hills in the plain of a society of self-sufficient independent people who lived in rough affluence. Most slaveholders owned a few people who lived with the family.

The idea that the South was the most prosperous part of the country may take some aback because the standard propaganda is that the Old South was poor and backward except for a few very rich. Actually that description applies better to the North before The War.

Consider: The 1860 census showed that in New York City there were women and children working 16 hours a day for starvation wages, 150,000 unemployed, 40,000 homeless, 600 brothels (some with girls as young as 10), and 9,000 grog shops where the poor could temporarily drown their sorrows. Half the children died before the age of 5, while in the South healthy black children proliferated in the rough abundance. No wonder that the slum refugees, unemployed, and foreign peasants who made up much of the Union army, envied, hated, and wanted to destroy the South.

Thomas Jefferson wrote a fellow Virginian in 1798: “It is true we are completely under the saddle of Massachusetts and Connecticut, and that they ride us very hard, cruelly insulting our feelings, as well as exhausting our strength and substance.” Jefferson thus laid out the story of American politics–powerful in the North by use of the federal government taking profit from the South.

Jefferson and his heirs were able to forestall the worst of the depredations until the War for Southern Independence in which the Northern capitalists conquered the government while whipping up hatred and fury against the Southern people’s feelings about keeping the slavery question in their own hands.

That independent South fought fiercely and at great sacrifice to preserve its freedom. In the process, most of its capital was destroyed, and in the “Reconstruction” what was left was ruthlessly looted by the conqueror. The concrete result of the war was the enrichment of dominant elements in the North. In fact, that was not only the result but the intent of the holy war of righteousness against the evil South. The American government became and remains a state capitalist regime–private profit at public expense, not “free enterprise.”

Cotton was the primary profitable crop. Its value to the world is indicated by the amount of it Northerners stole during the war and “Reconstruction.” In a society with capital destroyed, it could only be produced by borrowing enough to live on and produce the next crop. Thus Southerners could only exist by borrowing from the North. The authors document by overwhelming evidence the extent of Southern poverty in the sharecropping which ensued–debt peonage in which a majority of the black people were enslaved and an even larger number of white people, though not a majority.

Those who are as old as I am can remember when POVERTY was the main experience of the Southern people, a condition that has not entirely disappeared today. As the authors show the deliberate self-interested policy of the dominant Northern forces in control of the federal government has enhanced and continued Southern poverty.

This is seen in discriminatory legislation that prevailed for nearly a century and in the unending efforts to divide black and white Southerners and prevent what could have been mutually beneficial cooperation, a policy of division invented by the South-hating Republican Party and now massively pursued by the South-hating Democratic party.

The economic imperialism has been accompanied by a moral imperialism. Southerners have had “our feelings” perpetually hurt because of the backward conditions imposed on us and because our national character does not agree with the Northern tendency toward revolutionary abstraction.

The lesson to be had here: Southerners should stop being clueless supporters of the American empire and cannon fodder for its wars. We should stop being devotees of political parties that are and always have been our enemies. We should stop respecting those among us who collaborate with our enemy in exchange for a few crumbs from his table. We should realise who we are as a people and what our history as a people has been. We should begin to think for ourselves and consider our true position. We Southerners, black and white, should understand that we are a people, strive to refute the enemy of us both, and collaborate as people with the same interests.

In Dixie Rising: Rules for Rebels, published shortly after Punished with Poverty, the Kennedys lay out how a political program representing the true interests of the South could work. Such a movement would be a blessing not only to the South but a restoration of health to the degenerative diseases so evident in the United States.