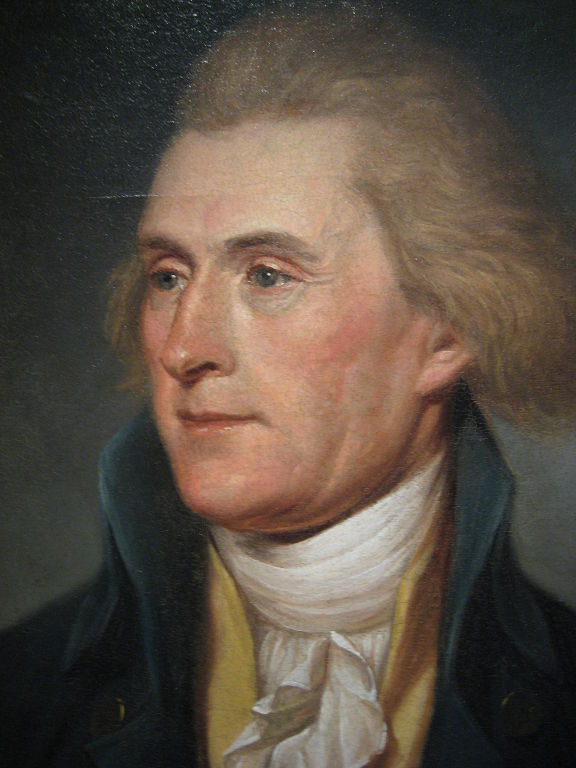

The question “Was Thomas Jefferson a genius?” might seem awkward to anyone who has spent any time studying Jefferson, for it admits an obvious answer: He was. I have consistently maintained that he was one of the most gifted thinkers of his day—“gifted” because of his Edison-like penchant for and persistency at hard study and hard work. He had an encyclopedic mind because he had inveterate curiosity and genuine interest in, and pursued study of, anything that might be useful for human betterment.

“Genius” has several definitions. As a noun, it can mean (1) a personal or locational spirit—e.g., the genius of Socrates. It can also mean (2) “a strong leaning or inclination”—e.g., Lord Byron had a genius for poetic prose. Again, it can mean (3) a defining feature of someone or something—e.g., the genius of Jeffersonian republicanism is the will of the people. Last, it can mean (4) a particular strongly marked capacity—typically, superordinary intelligence that has a particularly narrow focus.

The last definition is how we tend to use the word today. We ascribe genius to heady individuals who have been engaged with or absorbed by a prodigiously knotty problem, like laws pertaining to all bodies of the universe, and who have been successful in solving that problem. Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, William Hershel, and Albert Einstein come to mind.

Jefferson’s accomplishments throughout his life were numerous, and extraordinary:

- authors Summary View of Rights of British America (1774),

- is member of over 30 committees in the Continental Congress (begin 1775),

- coauthors Address on Taking up Arms (1775),

- authors a draft constitution for Virginia (1776),

- authors Declaration of Independence (1776),

- works on three-man committee to revise all the laws of Virginia (1776–1779) & Religious Freedom passes (1787),

- is governor of Virginia (1779–1781),

- is member of American Philosophical Society and future president (1780–1815) as well as lifelong patron and practitioner of sciences (checkerboard cities, inoculations, inventions, head of patent office, study of philology, archeology, paleontology, work as architect, &c.),

- is minister plenipotentiary to France (1784–1789),

- authors Notes on the State of Virginia (1787),

- is secretary of state during which time he pens numerous significant reports (1790–1793),

- collects and preserves over the decades Virginian laws (sent to Wythe 1796),

- is vice president (1797–1801),

- authors Kentucky Resolutions (1798),

- is president (1801–1809),

- authors First Inaugural Address (1801),

- goes to war with Tripolitan pirates (1802),

- births West Point Military Academy (1802),

- is moving force behind Louisiana Purchase (1803),

- sanctions Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804),

- puts into place the Embargo Act (1807),

- founds UVa (begins c. 1814), and

- records meteorological data from 1776 till death.

As we can readily see, Jefferson’s was not the focused genius of Galileo, Newton, Hershel, or Einstein. He studied law, politics, agrarianism, music, gardening, history, philology, poetry, philosophy, weather, archeology, and architecture. While he was adept at many—law, politics, philosophy, and architecture—he was not extraordinary at any, for his interests were too varied, his mind was too encyclopedic. He had, one might say with due regard for hyperbole, a desire for omniscience and the diligence, energy, and patience to pursue it. Early biographer B.L. Rayner writes in his The Life of Thomas Jefferson (1834): “His course was not marked by any of those eccentricities which often presage the rise of extraordinary genius; but by that constancy of pursuit, that inflexibility of purpose, that bold spirit of inquiry, and [that] thirst for knowledge, which are the surer prognostics of future greatness.” Patience and application he cultivated, and he was assisted by nature which gave him quick understanding, a logical mind, and a retentive memory.

Jefferson’s was, thus, was like the genius of Samuel Johnson, called “arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history.” Johnson was a biographer, literary critic, essayist, poet, playwright, sermonizer, editor, and lexicographer. In 1755, Johnson published his Dictionary of the English Language. It was understandably thought by most English speakers to be a fatuous work. Why do people speaking a language need a lexicon of that language? Speaking English demonstrates mastery of the words used. Hence, Johnson dolefully prefaced his Dictionary:

It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage, or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause, and diligence without reward.

Among these unhappy mortals is the writer of dictionaries; whom mankind have considered, not as the pupil, but the slave of science, the pioneer of literature, doomed only to remove rubbish and clear obstructions from the paths through which Learning and Genius press forward to conquest and glory, without bestowing a smile on the humble drudge that facilitates their progress. Every other author may aspire to praise; the lexicographer can only hope to escape reproach, and even this negative recompense has been yet granted to very few.

Johnson’s castigatory words betray the sentiment that his lexicon would not be understood and appreciated. In time, its significance would be understood and appreciated. Johnson would earn large celebrity in his later years, not merely for his dictionary, but also for his numerous other accomplishments.

Jefferson’s accomplishments, like Johnson’s, were abundant and varied. Thus, had he never inked the Declaration of Independence, he might still lay claim to being the greatest Founding Father. He was a genius, but, like Johnson, a productive genius, not, like Newton, a focused genius (physics and optics).

Yet Jefferson’s true genius was not his genius: that is, his genius3 was not his genius4. In other words, should one wish to characterize Jefferson by an epithet that gets to the essence of his person, that epithet would not be “superordinary intelligence.”

Jefferson’s true genius was his superordinary and selfless moral engagement of the Stoic sort. Jefferson’s accomplishments show keen interest in possession of knowledge of those sorts of things that work toward human happiness—amelioration of the human condition. His Declaration was, among other things, a universal proclamation of human equality, human rights. His decades of political involvement came for the sake of instantiation of republican principles of governing and at expense of his personal happiness. His heavy participation in the committee to reform Virginia’s laws was an act of selflessness. Notes on the State of Virginia was written to offer, among other things, a snapshot of the Virginia of his time for posterity. Jefferson’s membership in the American Philosophical Society was evidence of his love of science—a universal language of humankind.

And so, Jefferson’s true genius (defining feature) was not his genius (superordinary intellect), but his Stoic, selfless engagement in the affairs of fellow human beings with the aim of ameliorating the human condition. His true genius was his moralism—his love of his fellow human creatures, and through his amaranthine study of nature, his love of God.

Enjoy the video below, where the Colonel meets the Cap’n.

Thanks. … Ignoring the industrial myth, Mr. Jefferson still has his detractors, historically. There is no denying his active mind and insatiable thirst for, and attainment of knowledge. Superlatives are long redundant.

My favorite characterization of Thomas is by President John F. Kennedy in his address to gathered Nobel Prize winners at the White House:

“I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.

An unforgettable depiction that perfectly captures Jefferson! Thank you!

“Let those flatter, who fear, Sire. It is not an American Art”

From A Summary View…from my neighborhood

A memorable quote from one noted for memorable quotes….

You left out his being father of the Manifest Destiny, of westward expansion to the Pacific; since Jefferson’s knowledge of history compelled him to realize that a successful country depends on bi-coastal geography, if not more (ala the Gulf of America); and such a transcontinental territory would be indeed the greatest example in world history— and indeed, so it became.

Thus, while a famous quote by Otto von Bismarck, is that “Americans are a very lucky people. They’re bordered to the north and south by weak neighbors, and to the east and west by fish”; I credit Jefferson’s vision, rather than luck.