Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806), the son of freed slaves, was a natural scientist and mathematician. Born in Baltimore County, Maryland, little is known of the exact course of his life. He appears to have been mostly self-educated. His early years of manhood were spent mostly on his 100-acre tobacco farm, owned by his parents, freed slaves. He was, however, a tinkerer who was ever curious about how things of nature and of human contrivance worked.

In 1772, the Quakers Andrew, John, and Joseph Ellicott moved near Banneker’s farm to what is now Ellicott City to build gristmills. Having settled in Maryland, the Quakers befriended Banneker who was interested in astronomy. Andrew’s son George loaned Banneker several books on astronomy as well as ephemerides. Andrew Ellicott had been drafting ephemerides since 1780. In 1789, Banneker calculated an upcoming solar eclipse and sent his calculations to George. By 1790, Banneker created his own ephemeris which he hoped could be added to an almanac for 1792 (picture below is 1795). He found no willing publisher. In early 1791, he accompanied Andrew Ellicott to survey the land that would become Washington, D.C. We do not know how Banneker assisted Ellicott, but the assistance was short-lived, Banneker soon returned to his farm, likely to ready for the upcoming season.

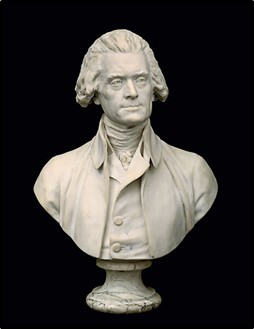

On August 19, 1791, Banneker took the liberty to write Thomas Jefferson, then secretary of state under President Washington. It is a long letter, and Banneker sends a hand-written copy of his almanac to Jefferson with the hope—though he never makes this explicit—of the latter’s patronage. Banneker drafts 15 short paragraphs (short for the time)—12 of which begin with “Sir.” Banneker mentions a report that indicates

that you are a man far less inflexible in Sentiments of this nature, than many others, that you are measurably friendly and well disposed toward us, and that you are willing and ready to Lend your aid and assistance to our relief from those many distresses and numerous calamities to which we [Blacks] are reduced.

Banneker also “drops” the name of Andrew Ellicott, whom Jefferson had appointed to survey the land to become Washington D.C.—Jefferson’s father Peter was a surveyor and Jefferson himself learned much from his father, though he was 14 when his father passed—and mentions that Ellicott had picked him to assist in his survey of D.C.

Jefferson replies 11 days later (Aug. 30):

No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colours of men, and that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence both in Africa and America. I can add with truth that no body wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body and mind to what it ought to be, as fast as the imbecillity of their present existence, and other circumstances which cannot be neglected, will admit.

I have taken the liberty of sending your almanac to Monsieur de Condorcet, Secretary of the Academy of sciences at Paris, and member of the Philanthropic society because I considered it as a document to which your whole colour had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them.

His response is perhaps supererogatory, as Condorcet is a Frenchman, who, like Jefferson, wholly committed to the cause of eradication of slavery.

Jefferson forwards the almanac with ephemeris to Condorcet on the day of his reply to Banneker.

I am happy to be able to inform you that we have now in the United States a negro, the son of a black man born in Africa, and of a black woman born in the United States, who is a very respectable Mathematician. I procured him to be employed under one of our chief directors in laying out the new federal city on the Patowmac, and in the intervals of his leisure, while on that work, he made an Almanac for the next year, which he sent me in his own handwriting, and which I inclose to you. I have seen very elegant solutions of Geometrical problems by him. Add to this that he is a very worthy and respectable member of society. He is a free man. I shall be delighted to see these instances of moral eminence so multiplied as to prove that the want of talents observed in them is merely the effect of their degraded condition, and not proceeding from any difference in the structure of the parts on which intellect depends.

Eighteen years later, Jefferson again mentions Banneker in a letter to Joel Barlow (8 Oc.t 1809). The letter concerns a recent book by Bishop Grégoire—De la Littérature des Nègres (1808)—a collection of 15 writings by Blacks and mulattoes.

Jefferson says to Barlow that Gregoire militated against Jefferson’s discussion of Blacks in his Notes on Virginia. He sent to Jefferson a copy of his book to confound Jefferson.

his credulity has made him gather up every story he could find of men of colour (without distinguishing whether black, or of what degree of mixture) however slight the mention, or light the authority on which they are quoted. the whole do not amount in point of evidence, to what we know ourselves of Banneker.

Jefferson, thus, is wholly unmoved by Grégoire’s anthology. The works are middling and, when compared to Banneker’s estimable almanac and ephemeris, show little.

Yet Jefferson is not wholly convinced of Banneker’s aptitude.

we know he had spherical trigonometry enough to make almanacs, but not without the suspicion of aid from Ellicot, who was his neighbor & friend, & never missed an opportunity of puffing him.

Did Banneker get assistance from Andrew Ellicott or from any other Ellicott?

Jefferson then returns to Banneker’s letter to him of August 19, 1791.

I have a long letter from Banneker which shews him to have had a mind of very common stature indeed.

Is Jefferson right to question Banneker’s aptitude?

Banneker’s letter to Jefferson does not indicate uncommon genius, to use a term commonly employed in Jefferson’s day. Yet Banneker’s genius is not that of belles lettres, but of mathematics, and Jefferson has nothing condemnatory to say of Banneker’s ephemeris. The letter, however, does betray anxiety.

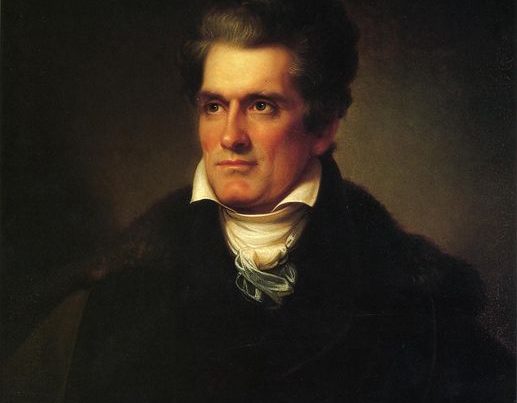

The great self-taught American astronomer, and a correspondent of Jefferson, David Rittenhouse, does address Banneker’s work. Rittenhouse writes in a latter to James Pemberton (6 Aug. 1791) that Banneker’s ephemeris “was a very extraordinary performance, considering the Colour of the Author.” He adds that there is “no doubt that the Calculations are sufficiently accurate for the purposes of a common Almanac.” That is scarcely a stunning endorsement.

Banneker was understandably irked: “I am annoyed to find that the subject of my race is so much stressed. The work is either correct or it is not. In this case, I believe it to be perfect.”

For more on Banneker, see Louis Keene.

Enjoy the video below….

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.