Originally published at A Memoir of the Occupation.

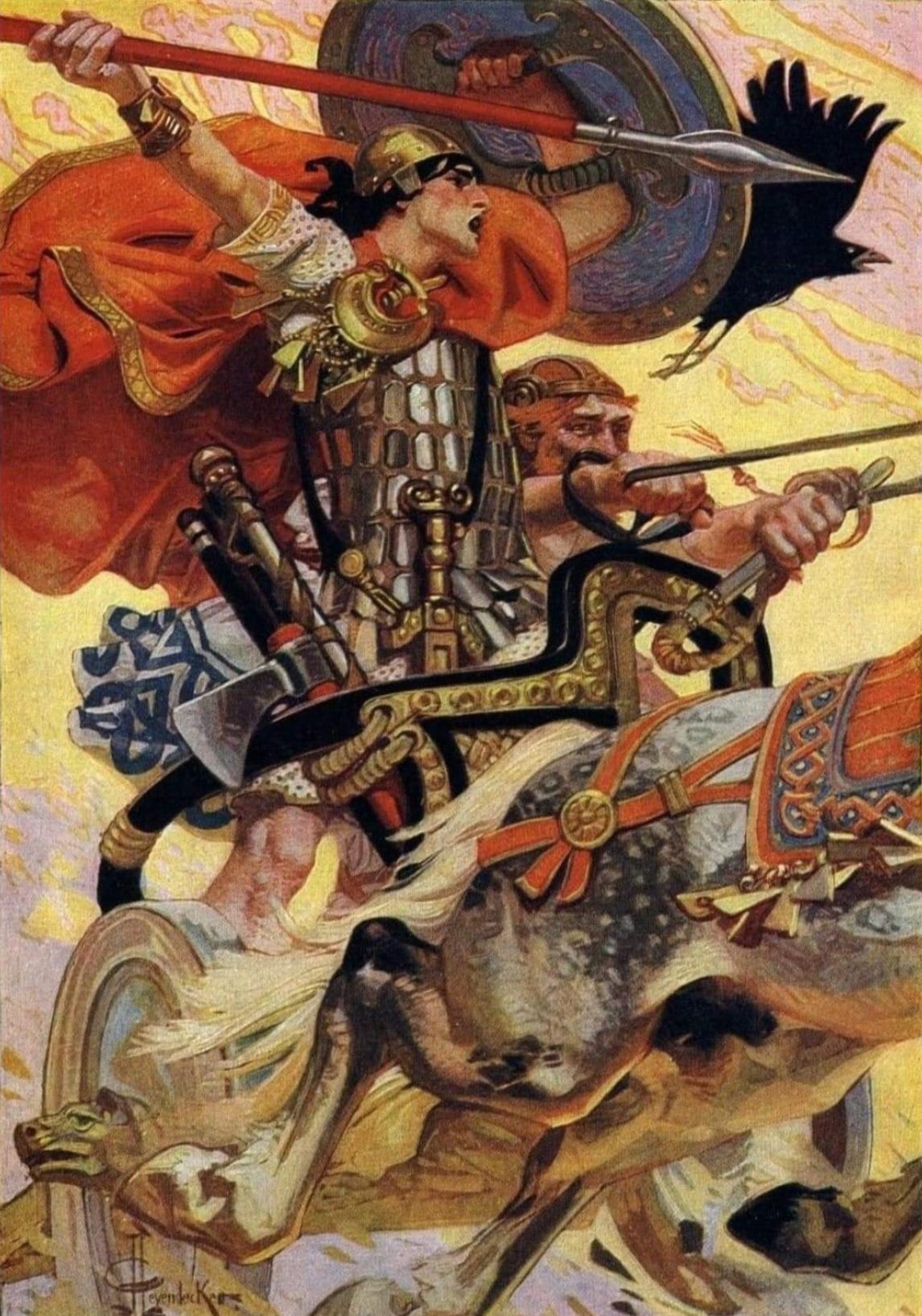

At the summit of ancient Irish literature stands Táin Bó Cúailnge, or The Cattle Raid of Cooley. It is the story of Queen Medh of Connacht and Cúchulainn, mightiest of the Knights of the Red Branch sworn to the service of King Conchobar of Ulster, and the war they fought over the Donn Cúailange, the legendary Brown Bull of Cooley.

The story begins in the bedroom of Queen Mebd and King Ailill, who rule the western kingdom. They’re engaged in “pillow talk,” rather arguing about money. Or more specifically, which of them is the wealthiest? Queen Mebd, rightfully proud that she is the most noble and celebrated daughter of the High King of Ireland, insists her treasury is richer than the King’s. King Ailill dismisses her with a laugh. No, woman. It’s me.

So the servants lug the royal hoards to the courtyard for an official reckoning. Cauldrons and buckets, bracelets and thumb rings, cloths patterned in plaid, check and stripe. But the value of each hoard is found to equal the other. Perhaps there’s more on the hoof? Sheep are called from the pastures, horses from their paddocks. No help there, either: the Queen has a prize ram, and so does the king; Ailill has a prize stallion, as does Mebd.

So the cattle are rounded from the woods and wastes. All are claimed, reckoned, counted – lo and behold, a tiebreaker! Finnbennach the Whitehorned: a bull, but not just any bull, but a renowned champion of the herd, and the sole possession of King Ailill. Queen Mebd is wracked by existential anguish. The King has a bull, and she does not. And to Mebd it was as if she hadn’t a single penny, for there was no bull to equal Finnenbach among her cattle.

Fortunately, there is in Ireland a bull of incomparably greater value: the Donn Cúailange, the Brown Bull of Cooley. Queen Mebd dispatches her messenger Mac Roth to owner Dáire Mac Fiachnawith. The Queen asks to borrow the Donn Cúailange for a single year, after which she will return with interest of fifty heifers, a piece of the smooth plain of Ai as big as all [his] lands, a chariot worth thrice seven bondsmaids as well as the friendship of my thighs.

Mac Fiachna consented – who wouldn’t? – and was nothing short of thrilled. He leaped up and down on his couch and the seams of his flock mattress burst beneath him. He even promises to personally escort the Pride of the Herd to Queen Mebd herself in Connacht.

That night, though, Mac Roth and his men get drunk. One boasts that had Mac Fiachna denied the Queen, they would have simply taken the prize bull by force. Mac Fiachna hears of this and is furious. The friendship of Queen Mebd’s thighs is but vapor when a matter of honor is concerned.

Look, Mac Roth pleads. You can’t pay attention to what people say when they’re drunk.

All the same, Mac Roth, Mac Fiachna growls. I won’t be giving up my bull.

Mac Roth returns to Connacht and breaks the news to Queen Mebd. The remarkable woman is philosophical: There’s no need to iron out the knots on this one, Mac Roth, she says. For it was known that if the bull were not given willingly, he would be taken by force. And taken he shall be.

And so begins the Táin, which scholar Kenneth Jackson describes as a window into the heroic society of Ireland’s Iron Age: “a warrior society in the sense that it is organized for the warfare that is its business.” Cattle are a store of value, a measure of wealth; raids on the enemy’s herds are a perfectly licit way of accumulating wealth. The Táin is but one of hundreds of such epics.

And what about these warriors? “Irish heroes are extremely touchy on points of honour and bound to avenge any sort of insult with the greatest savagery,” Jackson writes. The mightiest Irish hero of them all: Cúchulainn, the “hardest man” in Ulster, the son of a mortal mother and the god Lugh. When wounded, he is healed by Morrigan, the goddess of war. His father Lugh grants him the power to shift his shape and invoke a berserker-like frenzy. As the army of Queen Mebd marches on Ulster, he and chariot-driver Laeg bar their passage at every ford – running water is of profound significance in Irish legend – and demand single combat. The warriors of Ulster do not retreat. We still stand our ground, the warriors of Ulster say before the final battle, though the earth should split under us and the sky above us.

One of the more remarkable features of the Táin are its descriptions of the land itself.

The next morning Ailill’s charioteer Cuillius was at the ford washing the wheels of his chariot. Cúchulainn slung a stone at him and killed him. Hence the name Áth Cuillne, the Ford of Cuillius, at Cúil Airthir.

The next morning a hero attempted [to cross the River Cronn]. His name was Úalu. He shouldered a great flagstone to steady himself against the current. The river upended him, stone and all. His grave and stone are still there on the roadside by the river. They call it Lia Úalann, Úalu’s standing stone.

The Ireland of the Táin is alive. There are no abstractions, no eternal principles. There are instead people, specific individuals, who accomplished prodigies of valor and spilled their blood in this specific place. Their deeds and blood baptized, sanctified the land; to know that, to understand the memories held by the land is to achieve a sort of contemporaneity. The past is not dead, as William Faulkner once wrote. It’s not even past.

The landscape as a map of the past, was once how people – our ancestors – remembered and thought of themselves. And the Celtic peoples, if nothing else, know defeat, banishment, exile, dispossession. One can understand the importance of preserving those memories.

The origins of the people known as Celts is beyond the scope of this project[1]. It might be simplest to state, as did one Greek geographer, that Celts came from the west as Sythians did from the east. The best and most fair-minded overview is (IMHO) provided by Barry Cunliffe in The Ancient Celts. The Keltoi were first recorded in the 6th century BC, when Greek ethnographer Hecataeus of Miletus named cities founded by Celts in what became France and Austria.

The Celtic peoples early on displayed some cultural traits or habits that have remained remarkably consistent through the millennia. Plato, among others, noticed that the Celts enjoyed drinking and often did so to excess. But more than that they liked to fight. Strabo: “The whole race is war-mad, high-spirited and quick to battle, but otherwise straightforward and not of evil character. And so when they are stirred up they assemble in their bands quite openly and without forethought . . . They are ready to face danger even if they have nothing but their own strength and courage.”

In the 4th century BC a Celtic warband crossed the Alps into the Po valley. They founded settlements, including what became Milan, but soon bumped into the Romans. In 390 BC a Celt warband destroyed a Roman army at the battle of Allia. These are not civilized people, a consul thundered to the rattled citizens. But wild beasts whose blood we must shed or spill our own. Rome did just that in 225 AD at Telamon, in what is now Tuscany. The legions faced a “frightening” army of “finely built men,” Polybius records, the leading companies “adorned with gold torques and armlets.” The Romans routed the Celts and over time swept them from the Po Valley ; remainders were promptly Romanized. The refugees may well have fled their cousins in what is now France, which is where Julius Caesar found them. “Gaul contains three peoples: the Belgae, the Acquitani and the Gauls proper,” Caesar wrote. The Gauls, he said, call themselves Celts.

Commentarii de Bello Gallico is Caesar’s well-known account of his eight-year campaign to compel the obstreperous Gallic and Germanic tribes to submit to the authority of Rome. All the fault of the Helvetii, a tribe in what is now Switzerland which decided to relocate from its Alpine meadows to the greener fields of Gaul. On the way they roughed up some tribes allied to the Romans, which naturally pleaded for “help.” The Romans were all too happy to provide. Caesar soon had a general uprising of Gallic tribes to contend with, the work of Vercintegorix, a chieftan of the Averni. Caesar suppressed it in the usual ultra-efficient and brutal Roman manner. Huge numbers were slain or enslaved; Vercintegorix was carried to Rome in chains and executed by strangulation.

Caesar also, in 54 and 55 BC. found time to mount the first and second Roman incursions to Britain. He claimed the tribes of the islands were “helping” Vercintegorix and his rebels. Anyway, Caesar landed in Kent, marched through what is now Middlesex, crossed the Thames and installed a submissive king. Along the way he made valuable observations. Britain, he observed, was heavily populated. While the tribes along the coasts claimed descent from the Belgae, those in the interior claimed to have always been there. The coastal tribes cultivated grain, the sort of intense agriculture familiar to the Romans. Not so the tribes of the interior. They were pastoralists who followed their herds, lived on meat and milk and dressed in clothes made of skins. These Britons, like Cúchulainn and trusty Laeg, fought from chariots. Caesar praised their impetuous courage, but said they lacked the stolidity and discipline of the legions.

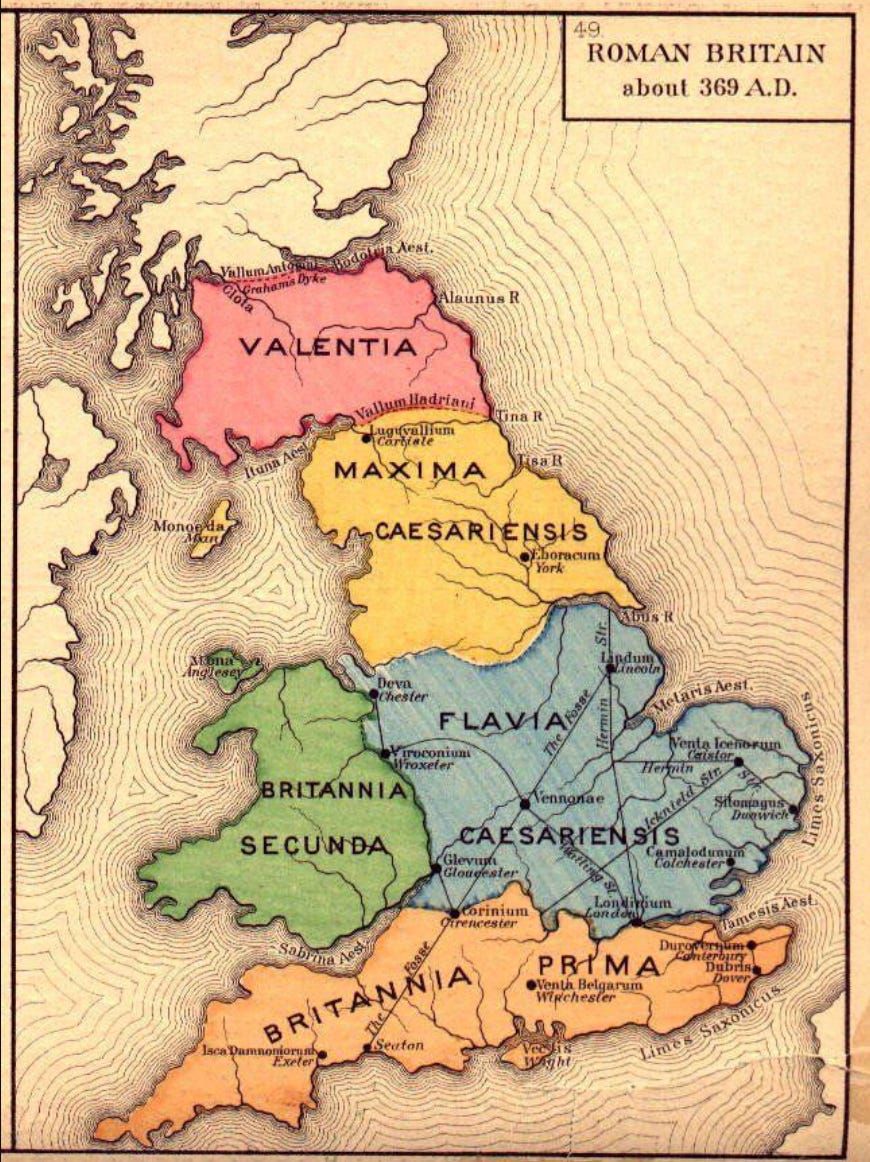

The conquest of Britain began under the emperor Claudius. Over time a stable Romano-British social order emerged, within limits. While Romans defeated a Caledonian confederation at Mons Graupis, their control never extended beyond Hadrian’s Wall. Or much beyond the Vale of Glamorganshire in Wales. As for Ireland, the Romans traded, but declined to attempt a conquest.

Rome, beset by external perils, withdrew its legions in the 5th century. Much to the dismay of the British, who had troubles of its own. Irish pirates (called Scotti by the Romans) were ravaging the coasts while Picts were pouring over Hadrian’s Wall. Angles, Saxon and Jutes were pillaging the southeast coasts; they were followed by the Northmen in 780 AD. In 871, St Alfred the Great became the king of Wessex and began the process of ridding England of the Vikings, a work continued by his children. When the Normans landed in 1066, Great Britain and Ireland looked like this: the Anglo-Saxons held most of the old Roman provinces while the Celts held the “fringes”: Cornwall beyond the Tamar; Wales behind Offa’s Dike; the Highlands beyond the Wall and Ireland in its entirety, beyond some trading posts established by the Norsemen:

The Normans found the Celts tougher nuts to crack. Wales “fell” to the Conqueror’s son in 1094 AD, but the Welsh chased the pests from their lands over the course of the next decade. In Scotland, Kings Alexander I and David I submitted, thus sparing their people the brutal “Harrowing of the North” visited upon York, but Robert the Bruce won independence at Bannockburn in 1314.

Gerald of Wales, son of a Norman father and a Welsh mother and sometimes chaplain to King Henry II, described Welsh society in the 12th century. Loyalty was to the clan, the tribe, not an abstraction in a far-distant capital. Bards maintained detailed genealogies and histories. And, just as Caesar had found them: a pastoral people with little interest in devoting time to tillage than could be better spend raiding the herds others, or more enjoyable pastimes such as feasts, where they “insisted on being served with vast quantities of food and even more especially intoxicating drink.” He discussed the Welsh genius for poetry and for music. They were “endowed with great confidence in speaking and great confidence in answering. They love sarcastic remarks and libelous allusions.” And, of course, the Welsh were “completely dedicated to the practice of arms.”

“Not only the leaders but the entire nation are trained in war,” Gerald wrote. “They esteem it to be a disgrace to die in bed, but an honor to be killed in battle.” They knew nothing of tactics other than to charge, charge and charge again. If routed, “tomorrow they march out again, no whit dejected by their defeat or losses.”

Celtic folkways have remained remarkably consistent over the millennia, then: a warlike, even violent people who prefer herding to tillage; loyal to clan, blood, place and memory rather than the abstractions of the modern state; who celebrate the heroic deeds of their ancestors through music and poetry for which they’ve shown a particular talent. It’s not a culture not optimized for efficiency and productivity and transmitted by a people without interest – or ability, some might say – in submitting to the demands of modernity and its homogenizing demons.

The conventional wisdom has long held that the South was settled almost exclusively by WASPs: white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. That’s incorrect, according to historians Forrest McDonald and Grady McWhiney. The core of Southern culture, they argue, is Celtic. It’s merely one of the countless things unknown about the South.

“By virtue of historical accident,” MacDonald writes, “the American colonies south and west of Pennsylvania were peopled during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries mainly by immigrants from the ‘Celtic Fringe’ of the British archipelago – the western and northern uplands of England, Wales, the Scottish Highlands and Borders, the Hebrides and Ireland.”

Irish migrations to the South began in the 17th century when hundreds, many as indentured servants, came to the Chesapeake colony. Thousands followed on the outbreak in 1641 of the brutal “Confederate Wars” that ended with Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland. To hell, Connaught or the sugar plantations of the Indies was the choice before many Irish. As Africans replaced the Irish in the Indies, the latter migrated to America, mostly the Carolinas. Another 20k-30k Irish were among prisoners and debtors transported to Virginia and Maryland in the 1700s.

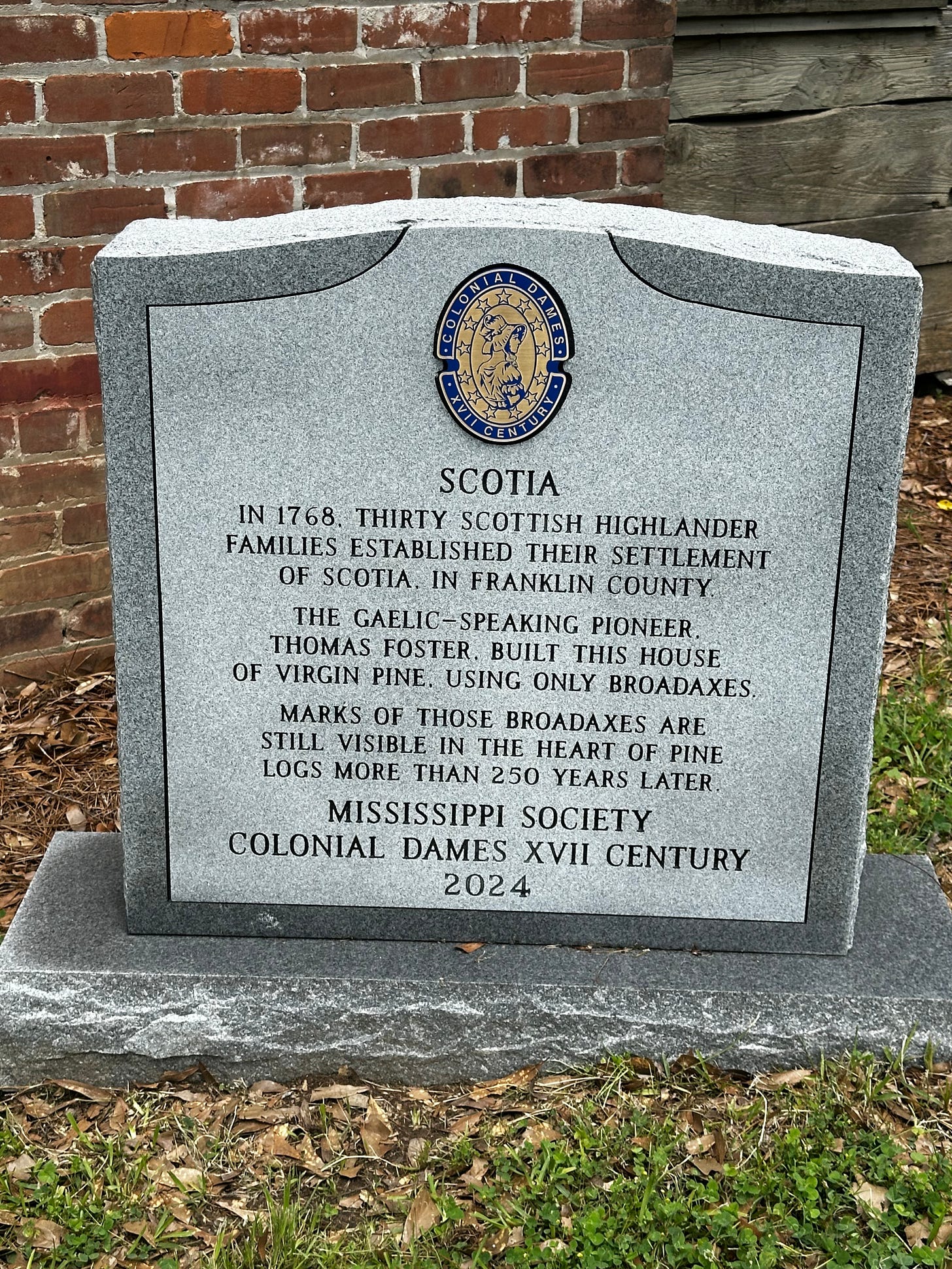

King James VI of Scotland, who became James I of England, commenced an all-out effort to extirpate the Gaelic culture of the Highlands in the early 17th century. “For most Lowland Scots (and, no doubt, for all Englishmen), the Highlands and the Islands were the cause of nothing but alarm, inhabited by an uncouth, barely-civilized warlike race whose only interest was war and whose main occupation were feuding and thieving,” Magnus Magnusson writes in his history of Scotland. The Statues of Iona in 1609 banned the carrying of firearms, forbade bards from glorifying warfare and required anyone owning more than sixty head of cattle to be educated in English. The Scots, of course, declined to submit. By the 18th century settlements of Gaelic-speaking Highlanders could be found in North Carolina and as far west as Mississippi.

But more Scots came by way of Northern Ireland. These were Scots-Irish, of whom anywhere between 130,000 and half a million arrived in the sixty years prior to the American revolution. These were not, as is widely believed, descendants of Lowland Scots planted in Ulster by James I, but “members of a traditional Gaelic (or Norse-Gaelic) society who had been moving back and forth between Ulster and the Highlands for nearly a thousand years.” Others hailed from the rough Anglo-Scottish borders, where for centuries “riding families,” or Border Reivers, had lived in a state of perpetual cross-border cattle raids, generational feuds. Sir Walter Scott collected their haunting ballads, tales of midnight raids and desperate battles in the northern wastes, in Ministry of the Scottish Border. Many of these were shipped to Ulster, from whence they made their wat to the new world. Those grim spirits became the most feared among the frontiersmen and the backbone of the Continental Army.

McDonald and McWhiney tested their thesis by compiling surnames from churchyards in the south and the east of England and from the counties of Antrim and Down in Ireland. These they compared with the Alabama census of 1850. 84% of Celtic names were represented compared to 43% of English names. The first Federal census of 1790, on the other hand, shows that almost 80% of New Englanders were of English origin. They also rely on the observations of travelers and other contemporary writers, which “found that the characteristic watts and values from antebellum Southerners were remarkably similar to those of most of the Celtic peoples of the British Isles.” On the other hand, the habits and disposition of Northerners “were precisely those that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writers found typical of most English people of the British Isles.”

The emphasis is mine. A simple Celtic/English dualism does not necessarily account for the revolutionary changes (as R.H. Tawney and Max Weber put it) that the Reformation and Enlightenment wrought in the souls of men. The Reformation represents, if nothing else, the beginning of the modern era that flowered more fully, or fatefully, in the Enlightenment: the rule of reason, of the quantitative over the qualitative. Work itself became an actual sacrament; disciplined, orderly habits were godliness itself. For the New Englanders, an Austrian traveler noted in the 19th century, “business constitutes pleasure and industry amusement.” Indeed, he said, “active occupation is not only the principal source of their happiness but they are absolutely wretched without it and know but the horrors of idleness.” God, in the old times, may have condemned Adam to earn his bread by the sweat of his brow but for the New Englander, toil was the entire purpose of life, the veritable way of the cross; profit, huge profits, were evidence of God’s blessings. “Observors from the 1600s through the 1800s agreed that as a rule, Northerners and Englishmen were industrious and business-minded farmers, traders, and manufacturers who were persevering, profit oriented, enterprising, often cold and stiff, sometimes ride and greedy. One Yankee boasted: ‘We’re born to whip universal nature.’”

McWhiney offers Henry V. Poor – from whence came the “Poor” in “Standard & Poor’s” as the prototypical Yankee. A native of Maine, Poor left for work early in the morning, returning home around seven or eight in the evening where he continued his labors. He regarded leisure as a sin; he rarely had time for his family and excused himself from vacations, as he could not forego “making a little money.” “He considered success in business to be a ‘demonstration of Yankee strength of character. Once he boasted to his wife after an especially profitable venture: ‘See what a Yankee can do.”

Poor eventually became the editor and part-owner of the American Railroad Journal. The railroad, he said, was “the great apostle of human progress.” Poor believed in Science: “By the new application of the powers of steam and electro-magnetism to the arts of life, the present age will be signaled by a more rapid change in the order of society, and the progress of the race, than any former one.” Poor, like countless other New Englanders, had jettisoned the stern God of Calvin’s Institutes and replaced Him with the Unitarian demiurge of progress. “The arc of the universe bends toward justice.” Poor and his fellow Americans fully believed that Yankee ingenuity could and would solve all the world’s problems, and that henceforth American life would represent a sort of celestial railway chugging single-mindedly toward the uplands of Utopia. Or, as Boston minister Dr William Elling Channery out it, “Prosperity is the goal for which they toil perseveringly from morning until night.”

Such “values” are less “English” than they are “modern,” representing as they do the triumph of the quantitative over the qualitative. But the relentless and unyielding quest for prosperity was foreign to the people who populated the South, and who found the backcountry uniquely suited to the lives they and their ancestors had lived far beyond from time immemorial. Southerners, McWhiney writes, “favored rural life and values over urban, frequently opposed such ‘modern improvements’ as railroads and banks… Invariably antebellum Southerners were described as hospitable and fond of pleasures; they enjoyed what money could buy, but they disdained people who devoted their lives to making money.”

And this Celtic culture was not merely different from that of the New Englanders: not merely “significantly’ different, but opposed, antagonistic and fated to collide in the bloodiest manner as the last remnant of the heroic age faced the champion of the age of the machine.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily the views of the Abbeville Institute.

“Look, Mac Roth pleads. You can’t pay attention to what people say when they’re drunk.”

Now this definitely has an historical lineage from the beginning until now!

“‘Irish heroes are extremely touchy on points of honour and bound to avenge any sort of insult with the greatest savagery,’”

So does this!

“…but opposed, antagonistic and fated to collide in the bloodiest manner as the last remnant of the heroic age faced the champion of the age of the machine.”

A blind man should have seen it.

Read Dr. Wilson’s is the the South Celtic? written in 2017.