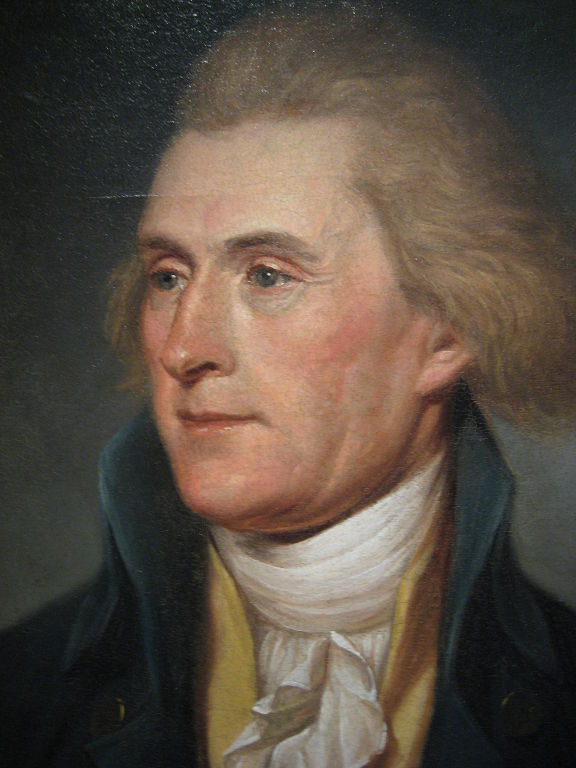

Thomas Jefferson has been depicted by many scholars as a pacifist, and a “conciliatorian”: that is, person adverse to conflict to solve problems and issues. He was a strict supporter of limited government and a militia, not a standing army, to defend and protect the country and to preserve liberty for the people. Yet he also birthed West Point Military Academy, and worked to professionalize and republicanize the United States Army officer corps? Why did Jefferson, who disdained standing armies and who preferred conciliation to conflict, establish a professional military academy? This essay will attempt to answer that question.

In 1794, Congress passed a law that established West Point as a Garrison for a Corp of Artillerists and Engineers with the intent that military officers would tutor cadets on the military science of fortifications, artillery and tactics. Additional legislation was passed in 1798 authorizing the appointment of specialized instructors, but no students had been appointed since 1794. These military officers were appointed by Federalists, particularly presidents George Washington and John Adams. In this period, the officer corps of the army was appointed and commanded by Federalists and it was led in the case of Fries’ Rebellion in Pennsylvania in 1794 by Jefferson’s political rival, Federalist Alexander Hamilton. Additionally, when John Adams was President, he expanded the army to approximately 12,000 men and placed Hamilton as his Inspector General. As the Adams’ Administration filled officer positions, they screened applications and excluded “anyone with the slightest hint of Republican sympathies.” This highly alarmed Jefferson and his fellow Republicans. Jefferson saw this exclusion as an assault on republican values and an attempt to institute an aristocracy of Federalists in the military through Federalist hegemony within the US Army officer corps.

When Jefferson took the office of president in March 1801, he came in with an intent to “republicanize” institutions formally in the possession of the Federalist Party and to establish and inculcate the republican values of progress and liberty throughout society. The military was no exception.

After his election in 1801, Jefferson laid out a distinct political program in his First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1801. One issue, in particular, concerned the role of the military. He states, “a well-disciplined militia, our best reliance in peace and for the first moments of war till regulars may relieve them; the supremacy of the civil over the military authority.” Thus, Jefferson and his Secretary of War, Henry Dearborn, pressed the Congress to approve legislation that would become the 1802 Military Peace Establishment Act, which would establish West Point Military Academy. The establishment of an academy of this was sort was from a broader discussion with Jefferson’s friend, Pierre Samuel Dupont Nemours, in a succession of letters in 1800 discussing proposals for a National University and education al reform in the United States. Jefferson asked Nemours, “What are the branches of science which in the present state of man, and particularly with us, should be introduced in an academy?” Nemours proposed an all-inclusive plan of national education with primary schools, colleges and four specialty schools. These schools were medicine, mines, social science and legislation. Nemours recommended “higher geometry” and engineering “urging forward the other sciences” to ensure the school would be a great benefit to the new republic.

Those recommendations appealed to Jefferson who was a firm believer in dividing and subdividing power throughout the republic from the ward, county, and state level up to the national for the republic with each level of responsibility assigned to them. The 1802 Act incorporated some of the ideas brought forth by Nemours in the exchange of letters.

The problem to be solved was this. Throughout European history, large standing armies had been created by monarchs, and their landed nobilities to enslave and control their populations and wage aggressive war on other nations. Jefferson was appalled by this despotic use of the military by European autocrats and intended to ensure that the United States Military, and the army in particular, would be an instrument of the people in safeguarding their liberties and the safety of the Republic.

West Point Academy was crucial to that idea. Although Jefferson valued the services of the militia, be believed that having a core of highly trained military officers was essential for a functional and efficient Republican army. Jefferson created an atmosphere at West Point predicated on an allegiance to Republican principles rather than birth, class, or wealth.

With the Military Peace Establishment Act, Jefferson transformed West Point Academy into a republican institution and “established it a source of Republican officers for the future.” One of the main was to establish the institution as Republican one was to ensure virtuous leadership in addition to a wider range of social class representation based up the criteria of virtue and talent for the newly appointed cadets.

In implementing the Act, Jefferson sought to reduce the size of the regular military force to save the Federal Government money. He wanted to reorganize the military chain of command so that less officers were needed. In his December 1801 message to Congress, President Jefferson announced that Secretary of War Henry Dearborn had complied a list “of all the posts and stations where garrisons will be expedient” and the “number of men for each garrison.’

Upon passage of the act and review of the current officer corps, Jefferson discharged many officers who were uncompromising Federalists. The Act also gave the president “exceptional powers over the new Corps of Engineers” who were “not bound by traditional promotion by relative rank and seniority.” Other parts of the reorganization were the opportunity to appoint 20 new Republican officers and the creation of a new rank in grade, ensign, a rank below second lieutenant. All those items became what was known as Jefferson’s “chaste reformation” of the army.

In the ensuing years after the 1802 Act, Jefferson slowly filled the ranks of the officer corps with Republicans over the next seven years of his Presidency. By the time he left office in 1809, 90 percent of the officers in the army were Republicans.

West Point Academy was crucial to Jefferson achieving his “republicanizing” of the army. Jefferson’s approach to replacing and filling the officer ranks is emblematic of his approach creating a system at all levels of society by empowering the “aristocracy of virtue and talent”, instilling a useful and republican education, and providing training which would equip and enable this aristocracy to lead the new republicanized army. Jefferson carefully reviewed officer applications by looking for virtue and talent in their backgrounds. Applicants came from various socioeconomic backgrounds and were to be strong republicans.

West Point’s curriculum consisted of teaching the cadets basic battle tactics, math, geometry, foreign languages, and engineering–all of which were intended to give them the basic skills to earn an officer’s commission and provide leadership in the new Republican army. Jefferson and Dearborn closely followed the school in the ensuing years to keep a close work on its political ideology, with republicanism being instilled in the officer corps to not only provide those with virtue and talent a place in leadership, but to create an officer corps that would propagate other values of republican government: free thought, liberty, morality, critical thinking (not blind obedience) and compassion. To Jefferson those values were essential to promote and preserve Republicanism in all institutions, including the military.

In closing, Jefferson said that he considered “that establishment [West Point] as of major importance to our country and in whatever I could do for it, I viewed myself as performing a duty.” The creation of West Point is certainly one of the great creations in education, military leadership and republican government in the United States, and possibly the world. It is a testament to the traditions of rewarding excellence without regard to wealth, birth or rank in society but as Jefferson said, in rewarding the “aristocracy of virtue and talents” that all republics should have at the helm of leadership. West Point fine accomplishment to be added to the immense list of contributions from a great lover of freedom, liberty and humanity.

Enjoy the video below….

West Point (and its kissing cousins, VMI and the Citadel) grew into as fine an institution in a true republic and civilized society as one could hope.

As a former enlisted man in the USMC I will throw in a cheer for the U.S. Naval Academy, as well (my brother was a fine naval officer many years ago and he may be reading this).

It is, however, a shame to see what they have been turned into with their feminization, “don’t ask, don’t tell,” general rebuff of manhood and a lack of standards.

The Long Gray Line, ain’t what it used to be. Thank you, you Washington political hacks and cowards!

But I did enjoy the article/

I don’t know about this. West Point Cadets received political appointments from Congressmen. Jefferson had the authority to make a handful of appointments, but most were by Congressional representatives and Senators. I went through the process in high school to get into the then new Air Force Academy and would have got an appointment after I joined the Air Force, but I turned it down because I was having too much fun as an enlisted aircrew member. My son was appointed to and graduated from Annapolis, then served six years in the Navy as a submarine and special ops officer. I’m not sure where this author got his ideas.

My “ideas” are presented from what I have read or witnessed. If you think that the military academies have not been restructured in the name of some modern (almost degenerate) political-closet-reform then you certainly are entitled to say so.

But I strongly disagree. I will also say the same has happened to the USMC, an outfit with which I am well acquainted—Parris Island, class of Jan 1965.

But I do thank you for your interest.