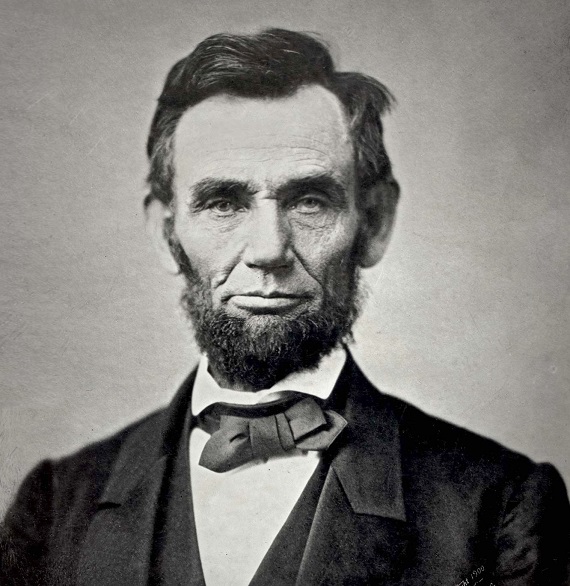

Back in early 1981 the brilliant Southern scholar and traditionalist, Professor Mel Bradford, was the leading contender to receive President Ronald Reagan’s nomination as head of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Bradford was the epitome of the accomplished and erudite academician, yet his deep-rooted Southern and pro-Confederate beliefs disqualified him in the eyes of many national “conservatives” such as George Will and Bill Kristol. Bradford’s worst sin, they asserted, had been that he had harshly (if with laser-like precision and accuracy) criticized the modern icon within the “conservative movement”—Abraham Lincoln.

Bradford’s major accusations were that Lincoln essentially “remade” the American constitutional system, asserting “equality” as the country’s foundational value and enlarging the ultimate power of the federal government at the expense of the states, and, thus, beginning a process of governmental expansion and control that continues largely unabated in our time.

It was largely criticism of Lincoln that became the new bar, the “red line” which one could not violate that doomed Bradford (and ushered in William Bennett at the NEH instead). Since then criticism of Lincoln is not acceptable, not tolerated by mainstream conservatives. Instead, the conservative establishment now heralds such neo-Reconstructionist historians as Allen Guelzo or even Marxist Eric Foner (a favorite of Karl Rove). Any dissent from the virtual canonization of Lincoln in contemporary American society usually comes mostly from Southern traditionalists and their allies, Paleo- (or Old Right) conservatives, who are usually then dismissed or derided by the establishment Republican Party, various pundits on Fox News and the present-day “conservative movement” as reactionary know-nothings, unable to understand the natural evolution of the American republic.

Yet, beyond Lincoln’s role in unleashing the power of an omnipotent federal government, there is another aspect of Lincoln’s background that should worry Americans—not only Southerners—just as much. It is perhaps the best guarded confidence in American history. It certainly isn’t something that the dominant “conservative movement” wishes to acknowledge, much less see debated publicly. Yet, the factual record is there for anyone with initiative and curiosity to see for himself: Abraham Lincoln not only had a favorable opinion of Karl Marx and his writings, but was at times sympathetic to socialist policies and ideas.

A few years back (July 27, 2019) a short article by Gillian Brockell appeared in the The Washington Post. Titled, “You know who was into Karl Marx? No, not AOC. Abraham Lincoln,” the author catalogues the connections between Lincoln and Marx, and the list is—or at least should be—alarming for conservative Americans. (I acknowledge my debt to Brockell’s investigative reporting for this article.)

In his first annual message—his first State of the Union address—in December 1861 he ends the address with a peroration on what the Chicago Tribune at the time called a meditation on “capital versus labor.” “Capital is only the fruit of labor,” Lincoln elaborated, “and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.”

Those words could have come almost directly from Karl Marx, but they were spoken by Lincoln. Fascinating, since the sixteenth president was an avid reader of the father of Marxism and corresponded with him during the War Between the States. Abraham Lincoln was not a declared socialist, certainly not in the modern sense. But Lincoln and Marx — born only nine years apart — were contemporaries. They had many mutual friends, read each other’s work, and, in 1865, exchanged letters.

During his only term in Congress during the late 1840s, Lincoln became a close associate of New York Daily Tribune editor, Horace Greeley. It was through Greeley’s paper that the ideas and program of the nascent Republican Party were spread. And these were not just the usual anti-slavery slogans we so often hear today when we read of the formation of the party. Often those positions sounded a great deal like socialism, including proposals for the redistribution of land in the American West by the federal government to the poor and emancipated slaves.

At approximately the same moment in time, across the Atlantic Karl Marx was penning his famous text, “The Communist Manifesto” (1848). The failed revolutionary uprising in Germany had compelled Marx to take refuge in England. Hundreds of thousands of other German radicals immigrated to and took refuge in the United States, settling in places like St. Louis, Missouri, where they would play a critical role in later securing that essentially Southern state for the Union in 1861-1862. According to historian Robin Blackburn, in his volume, An Unfinished Revolution: Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln, Marx even considered immigrating and going west to Texas.

According to Blackburn Marx believed that the two most significant things happening in the world in 1860 were “the movement of the slaves in America started by the death of John Brown, and … the movement of the serfs in Russia.”

In 1852 Charles A. Dana, an avowed socialist and managing editor of the Daily Tribune, hired Marx to be the paper’s English correspondent. Dana had been active previously in the utopian socialist experiment Brook Farm, and he carried his vision of a workingman’s utopia with him. Marx, in exile, was a natural fit as a correspondent, and for the next decade the founder of modern communism authored 500 articles for the New York flagship paper of the Republican Party, many of them front-page editorials formally expressing the journal’s position. And like other contemporary Republicans, Lincoln constantly read the Tribune, and certainly, then, he read and digested the writings of Karl Marx. Indeed, it was the support of the German radical immigrants recently come to American shores and the Tribune that propelled Lincoln to the Republican presidential nomination in 1860.

In 1862 Dana left the Tribune, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton making him Special Commissioner for the operation of the War Department. Essentially, he became “the eyes of the Administration,” as Lincoln called him, with an inordinate influence over the conduct of the War…and over Abraham Lincoln. His opinions were received by the president as gospel, and frequently they mirrored the editorials of Tribune journalist Karl Marx.

After Lincoln’s re-election in November 1864, Marx wrote to him (January 1865) as representative of the International Workingmen’s Association, a group bringing together socialists, communists, anarchists and trade unions, to “congratulate the American people upon your reelection.” Marx continues in his communication: “…the workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working class.”

The president’s response to Marx came by way of his ambassador in London, Charles Francis Adams. Adams declared that Lincoln considered the founder of Marxism to be a “friend” and that he possessed the “sincere and anxious desire that he may be able to prove himself not unworthy of the confidence which has been recently extended to him by his fellow citizens and by so many of the friends of humanity and progress throughout the world.” The Union, Lincoln added, derived “new encouragement to persevere from the testimony of the workingmen of Europe.”

But this was not Lincoln’s only tip of the hat to revolutionary social radicalism. In 1864 he met with the New York Workingmen’s Association where he insisted that “the strongest bond of human sympathy, outside of the family relation, should be one uniting all working people, of all nations, and tongues, and kindreds.”

Of course, Abraham Lincoln never declared himself to be a socialist, and many of his utterances were likely politically-motivated. Yet, he certainly viewed socialists—the workingmen’s unions—as staunch allies in his war against the South. As author John Nichols in his study, The “S” Word: A Short history of American Tradition…Socialism (2015), comments about “the left leanings of founders of the Republican Party”: “…it is indisputable that the Republican Party had at its founding a red streak.”

In spite of the current historical legerdemain and outright falsification of history, Lincoln continued to be an icon of the Left after his death. In the early twentieth century Socialist Party USA leader, Eugene V. Debs, saluted Lincoln as a fellow “revolutionary.” And in the later 1930s American communists flocked to volunteer for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to fight, they claimed, “against fascism and Francisco Franco” in Spain’s bloody civil war.

One hundred years after Lincoln’s death, in February 1968, in an address praising communist W. E. B. Du Bois, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. (reputedly a Republican, like his father) spoke in praise of Lincoln’s Marxist connection: “…Abraham Lincoln warmly welcomed the support of Karl Marx during the Civil War and corresponded with him freely. … Our irrational obsessive anti-communism has led us into too many quagmires….”

Every time, then, that a Dinesh D’Souza, Brian Kilmeade or Victor Davis Hanson on Fox News, or a representative of the Claremont Institute praises America’s sixteenth president and claims him for the conservative movement, while condemning those old “racist” Southerners, alarms should sound for genuine believers in the Framers’ Constitution.

Boyd Cathey is my favorite contributor to the Abbeville Institute.

What is happening in Ukraine right now is very similar to what happened to the South during Lincolns war. Putin and Lincoln, two peas in the same pod.

A friend just directed me to this article. Not the first I’ve read from this site, won’t be the last. Just stunning how deep Lincoln’s immorality ran and how far people have gone to lionize this veritable monster and tyrant.