There is no better place to begin understanding the party politics of the post-reconstruction South than with the Fourth of July celebrations organized by the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers in Memphis, Tennessee, 1875. The Pole-Bearers were a “fraternal society,” or mutual aid society, for the welfare and defense of black people. In attendance at this event were various former Confederate generals and Southern Democrats, who had been invited by the black leaders for purposes of celebration, reconciliation and, indirectly, to try and persuade their members that they would be better off voting for the Democratic party and not the Republican party. The black leaders expressed a wish to “reconcile” with white Southerners as they felt betrayed by their experience of the previous ten years with the Radical Republicans, whom they accused of treating black people as mere tools for their political games.

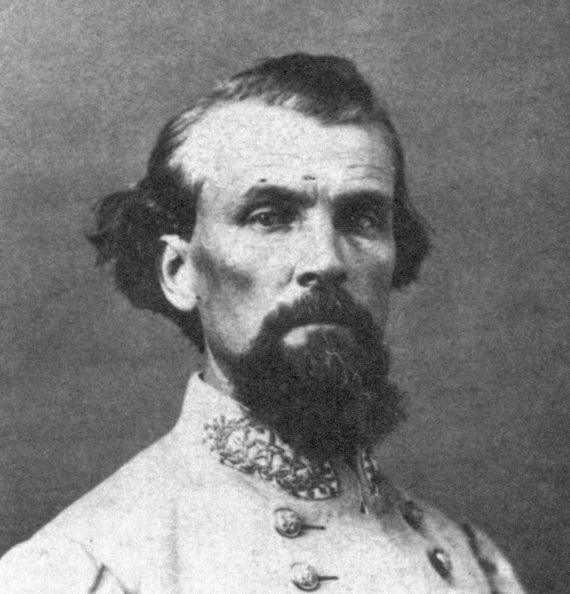

Nathan Bedford Forrest seems to have been essentially the guest of honor at this event. He was certainly the star of the show. He was presented with a bouquet of flowers by the black ladies, which strikes modern readers – who know nothing of Forrest’s popularity – as astonishing. Forrest delivered a brief but now well-known speech in which he encouraged an end to racial conflict. The event was covered at the time by the Memphis Daily Appeal and another local newspaper.

This event is revisited annually in debates surrounding Nathan Bedford Forrest Day in Tennessee. Those who wish to denigrate Forrest’s legacy insist on describing him as a KKK leader, their implication being that he was hostile to black people. Defenders of Forrest, on the other hand, attempt to portray him as some sort of civil rights activist. The notion of Forrest being a social justice warrior is not quite accurate, and results from reasoning in the reverse – as we are now accustomed to viewing race issues as “civil rights” issues, the assumption is that any white person showing friendship to black people in 1875 should be understood as a civil rights activist. In fact, Forrest’s opinions on this matter had little to do with civil rights and more to do with the commonsense need for the races to live in harmony rather than in perpetual conflict and violence. Forrest understood, far better than the race hustlers who now parade themselves as civil rights activists, the need to bring racial conflict to an end and work together towards peace. It was a theme echoed elsewhere by another former Confederate General who is also, like Forrest, rumored to have been in the KKK, John B. Gordon. Gordon once expressed, to a Congressional committee, his opinion that

“I am willing to swear until I am gray that the negroes and the white people can live together in Georgia peaceably and happily if they are not interfered with.”

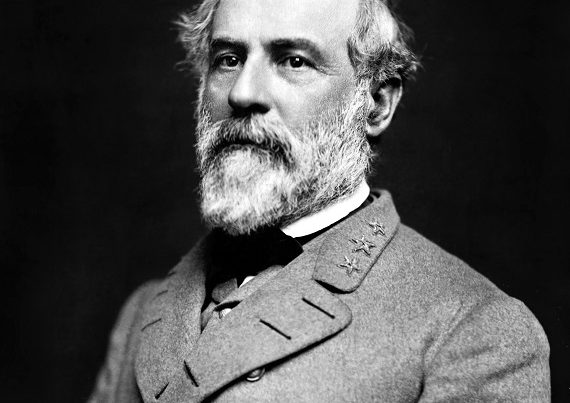

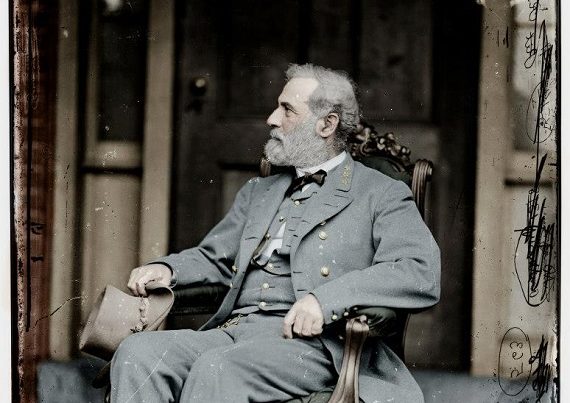

In his Pole-Bearers speech, Forrest wisely avoided getting mired in party politics. Nor did he address the many rumors that swirled around him, other than to say he knew people told lies about him and that he took comfort in knowing that those who stood with him, black and white, knew the truth. In this he followed the prudence of Robert E. Lee, who also refrained from publicly debating the slanderous lies that were told about him. Debating rumors is always unedifying. All that accomplishes is to inject fresh life into the rumor-mill, as expressed in the popular edict, “do not feed the trolls”. One could say this is indeed the Christian way, to “let your light so shine before men”, and those interested in understanding the truth will see your true character.

In his speech, Forrest focused on his commitment to the common interest of all the people of the South:

“I have not said anything about politics today. I don’t propose to say anything about politics. You have a right to elect whom you please; vote for the man you think best, and I think, when that is done, you and I are freemen. Do as you consider right and honest in electing men for office…. I came to meet you as friends, and welcome you to the white people. I want you to come nearer to us. When I can serve you I will do so. We have but one flag, one country; let us stand together. We may differ in color, but not in sentiment…. Go to work, be industrious, live honestly and act truly, and when you are oppressed I’ll come to your relief. I thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for this opportunity you have afforded me to be with you, and to assure you that I am with you in heart and in hand.”

Gideon Pillow, who was also present at this event and spoke after Forrest, did not follow Forrest’s example in diplomacy. He launched into a lengthy speech warning his audience against being beguiled by the political wiles of the Republicans, whom he termed the “enemies of the Southern white people”.

“You were misled at the end of the war by bad men of the Republican party,” Pillow continued. “If you had not put yourself in the hands of the enemies of southern white people, but had placed your confidence in them and had cooperated with them in necessary reforms in the policy of State government, they would have been your allies and would have adopted such forms of legislation as would have greatly advanced your interests.”

Republican party propaganda certainly played a notable role in fueling racial conflict. The historian William Dunning explains:

“From the Union soldiers, from the northern missionaries and school-teachers, and from bureau agents of every grade the freedmen had heard proclaimed for years now, in all the changes from mysterious allusion to intemperate asseveration, the virtues of the Union and Republican party which controlled the North, and the vices and heresies of the Democrats which had brought ruin to the South.”

Pillow’s message was therefore that the black people of the South had made a terrible mistake in trusting the federal government to help them meet the challenges of social and economic progress, when instead they should have trusted to hard work, education, and – as Pillow saw it – their common interests with the white people of the South. He also reminded them that legal equality had been achieved after the war (by the Civil Rights Act 1866), and that it was up to them to build on this legal equality through hard work, industriousness, and education.

Rather than being treated as an opportunity for reconciliation between North and South, the Reconstruction process had been treated by the Republican carpetbaggers as an opportunity for self-serving race-craft and self-enrichment. Samuel W. Mitcham explains: “To control the South politically, the Carpetbaggers practiced the old political practice of ‘divide and rule.’ They deliberately pitted black Southerners against white Southerners, a tactic which kept them in power for a number of years.” Mitcham adds, “They used their time in office to enrich themselves, loot the defeated Southern states, and poison race relations in the South for decades.” He further explains that:

“the Union League and Northern politicians sowed the seeds of divisiveness between the races, in order to enrich themselves. And enrich themselves they did. Using the power of the government they controlled, they issued bonds which they purchased for as little as one cent on the dollar. The South had to redeem these bonds later at their full face value, yielding a huge profit for the Carpetbagger. The city debt of Vicksburg, for example, grew from $13,000 to $1,400,000 in just five years of Republican rule.”

Also instrumental in fomenting racial conflict were the “Union or Loyal Leagues,” described by Dunning as “secret and oath-bound organizations, with awe-inspiring rites and ceremonial” whose aim was to see that “new voters were duly trained for their political activity,” ensuring that the freedmen would vote for the Republican Party. This goes a long way in explaining why black people who previously supported the Confederate cause—even remaining in their positions after emancipation—flocked in such great numbers to the Republican party during Reconstruction. Dunning recounts how white Southerners had attempted in vain to find common cause with them: “In some localities systematic attempts were made to persuade the blacks that their best interest lay in harmony with the native [i.e., Southern] whites; but the results were pathetically insignificant.”

Forrest had seen all this unfold in the ten years after the war. He was no civil rights activist. He did not argue, as the social justice warriors do today, that diversity, equity, and inclusiveness must be enforced on the South at the point of the bayonet, nor did he campaign for either segregation or an end to segregation. He was not a “progressive”. He did not believe that it is the job of the government to create racial harmony by dictating people’s thoughts and actions. His message was simple – that the path to prosperity lies through peace, through racial harmony, and not through race-craft, corruption, and violence.

The views expressed at AbbevilleInstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.