Prehistoric warfare was total war in which victors normally killed all enemy women, children, and adult males, according to groundbreaking research published by Lawrence H. Keeley, in his book War Before Civilization1.

Keeley wrote that primitive war was always a struggle between societies and their economies, and warriors carried out that struggle. Rome fielded great armies, in historical time, and sometimes killed whole societies that opposed them. The destruction of Carthage is just one example. After Rome’s decline, Western Europeans preferred to wage war between specialized forces. Initially those were armored noblemen, then mercenaries, and then professionals. Napoleon’s citizen army signaled the beginning of the widespread impressment by European nations of male civilians into military service.

In The War of the World2, Niall Ferguson noted that, “Throughout European history there had been social and institutional as well as technological limitations on war, which limited the mortality rates inflicted by organized conflict.” The Thirty Years War was a bloody exception to the generally limited goals for which states fought and to the warfare engaged in by them to reach those goals. The peace treaties that ended those wars normally resulted in minor transfers to victors of a little territory with its population and payment of a moderate indemnity

Western European nations renounced total war after the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and fought their wars between uniformed armies and away from major urban areas.

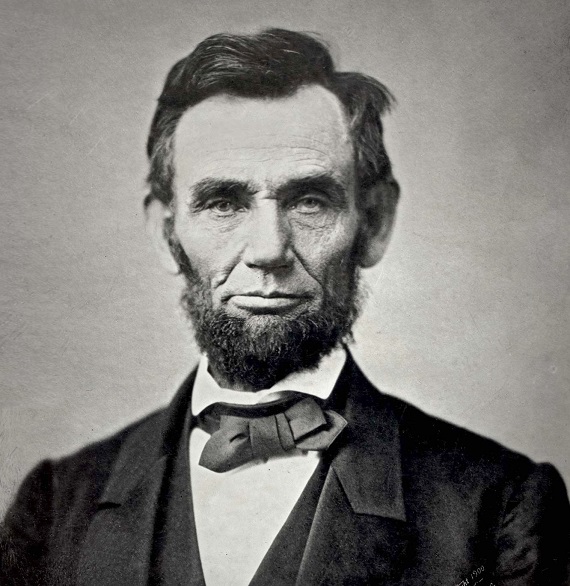

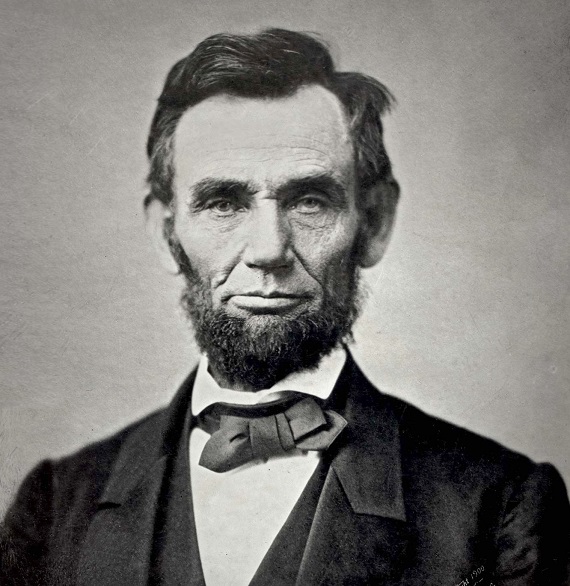

Keeley noted that many military historians claim that Grant and Sherman defined the current rules and doctrines of Western civilized warfare. They were only partly right. Grant, Sherman, and other U.S. generals did conduct total war against the Confederacy, but Lincoln gave them authority and encouragement to do that, and modern, western nations’ wars against whole societies began again in North America with his war and the U.S. Army.

One example of Lincoln’s support of total war must suffice here. It began in April 1862, when Col. John Basil Turchin, a former Russian officer, encouraged his regiment, the 19th Illinois Volunteer Infantry and also the 24th Illinois, to commit atrocities against the citizens of Athens, Alabama.

Turchin’s troops, many drunk, attacked the town’s 1,200 residents, and stole from stores and private homes, and burned private buildings. They sexually attacked both black and white women, and civilians that resisted were taken away at bayonet point. One pregnant white woman miscarried and died after she was gang raped. In the weeks after the Athens atrocities, Turchin continued to openly disobey orders to protect all private property and ordered his men to burn the nearest farm house when they were fired at from an ambush.

When Turchin’s commanding officer learned about the atrocities in Athens, he ordered Turchin court-martialed. During a 10-day-long court martial, Turchin refused to refute the atrocity charges, and was found guilty and dishonorably discharged on August 6, 1862. His atrocities and dishonorable discharge were called to Lincoln’s attention, but Lincoln still arranged for him to be appointed a brigadier general. By mid-1862, Turchin’s methods were in widespread use by the U.S. Army.

Turchin’s methods appealed to Lincoln because though U.S. military forces had been able to overwhelm the Confederacy with superior numbers and weapons, they had not been able to defeat Confederate armies. As a result, Lincoln introduced total war against Confederate society, with war crimes against civilians and POWs, and theft and destruction of enemy property, as standard operating procedures. From that experience the U.S. learned that violence towards enemy civilians and destruction of enemy civilians’ property was an important element in winning a war.

Keeley wrote that, “It was not until World War II that the rest of the civilized world followed.” In fact, not all Western and Central Europe nations avoided total war, from the mid-1600s until World War II. Both the U.S. and U.K. conducted total war in decades after Lincoln’s War and well before World War II. A few examples must suffice here.

From the 1860 until the late 1870s, the U.S. slaughtered Indian men, women, and children to clear the northern prairie for white settlement and restrict Indians to reservations. From 1899 until 1913, the U.S. Army killed 300,000 Philippinos, and used concentration camps and torture to conquer that country.

During their Second South Africa War, from 1899-1902, when their army of 500,000 men was unable to beat about 40,000 Afrikaaner farmers, the U.K. carried out a scorched earth policy in the Afrikaaner republics and forced women and children into concentration camps where more than 26,000 died from hunger and disease.

Before and during U.S. entry into World War I, the U.S. and U.K. prevented all food and civilian products from reaching Germany, and continued this blockade after the armistice in order to force Germany to give up gold needed to buy food for its starving population.

In 1919, after the U.K. was given a League of Nations mandate to govern Mesopotamia (now Iraq), Kurds in the north rebelled. Churchill, then U.K. colonial secretary, sanctioned the use of tear gas on Kurdish tribesmen in Iraq. Iraqi Arabs then resisted from June to October 1920. In suppressing their revolt, the U.K. bombed civilian targets and Churchill, then head of the U.K.’s War Office, advocated using poison gas.

During World War II, the U.S. and U.K. bombed civilian targets in Germany in order to destroy Germany’s ability to fight. After the war ended, the U.S. and France caused the deaths of 1,250,000 German war prisoners by sickness and exhaustion. (See Other Losses3, by James Bacque) Pure hateful vengeance against helpless war prisoners was the reason.

When World War II ended, at the Soviet Union’s urging, many German military and civilian leaders were tried for ex post facto war crimes, that is for actions that were not crimes when committed. Key Nazi leaders, civilians, military men were tried in Nuremberg for “waging aggressive war”. At those trials, accusers were allowed to be prosecutors, judges, and executioners. These “prosecutors” were often as guilty of crimes and atrocious as numerous as those with which the accused were charge.

Some leading citizens, in winning countries, thought those trials and punishments would discourage future aggression and reduce brutality in warfare. However, conflicts around the world have since become more brutal, and belligerents have used every destructive measure available to avoid losing and possibly facing trial for war crimes. The exception has been where both parties have been armed with atomic weapons.

In Profiles in Courage4, John F. Kennedy wrote that after the Nurnberg trials ended, U.S. Sen. Robert Taft said that he strongly opposed them, because they were based upon ex post facto laws, which the U.S. constitution expressly forbids. He said that using ex post facto law in order to punish a defeated enemy was a significant error. Taft was damned by the press, constituents, legal experts, and other senators, and, as a result, probably lost his party’s presidential nomination. Many years later, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas agreed that the Nurnberg Trials were unconstitutional.

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. implemented a “Strategic Hamlet Program” which attempted to force South Vietnamese villagers into guarded villages from which they could not supply the insurgent Viet Cong. This concept was similar to that used by the U.S. to crush Philippine independence and by the U.K., from 1899-1902 to crush two Afrikaaner republics.

Population-concentration villages had been an important part of the U.K.’s successful suppression of a guerrilla war in Malaya from 1948-1960. However, the Malaya program controlled a rebellious, Chinese-minority population, while the U.S. program tried unsuccessfully to control the great majority of South Vietnamese. South Vietnamese that stayed in villages from which they had been ordered to move were then in “free fire zones” and subject to random artillery fire, bombing, and sometimes to murder by U.S. and allied troops. (See Kill Anything That Moves5, by Nick Turse)

During the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988, the U.S. supplied Iraq deadly chemical and biological weapons from U.S. corporations. Those included viruses such as anthrax and bubonic plague. The U.S. also arranged, through a Chilean front company, to supply Iraq with cluster bombs.

It is therefore fair to say that for the U.S. and U.K., prehistoric, total warfare returned with Lincoln’s warfare policy, and that.an important part of his legacy is lethal, violent warfare of epic proportions. In modern warfare, a Lincolnian principal now prevails, and the end justifies the means.

- Lawrence H. Keeley, War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996)

- Niall Ferguson, War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (New York: The Penguin Press, 2006)

- James Bacque, Other Losses: an Investigation into the Mass Deaths of German Prisoners at the Hands of the French and Americans after World War II (Vancouver, British Columbia: Talon Books, 2011)

- John F. Kennedy, Profiles in Courage (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1955)

- Nick Turse, Kill Anything That Moves: the Real American War in Vietnam (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2013)